|

Bourne Castle

The existence of a castle in Bourne in early times is part of our local folklore although concrete evidence that any such building was ever here is rather sparse. Today, we regard the hills and hollows in the Wellhead Gardens around St Peter's Pool as the remains of this fortification and many of the guide books support that tradition but the foundations for such a belief are by no means sound and rest almost entirely on occasional documentary references down the centuries and inadequate archaeological excavations 150 years ago. The architect of Bourne Castle is generally believed to have been Baldwin Fitzgilbert who turned the parish church into a monastery and probably laid out a new market place in trying to make Bourne a caput or headquarters worthy of the king's relative. During the reign of Henry I (1100-1135), the Lord of Bourne was William de Rullos but Fitzgilbert married his niece Adelina and thus came into the possession of Bourne by the right of his wife. There is little evidence of his castle and he is more celebrated for founding the abbey in 1138, one of the five monastic houses attached to the Arrouasian congregation, a sub-division of the Augustinian order, which is well documented. Proof of such a building then is scarce but what emerges from the available written evidence is not so much a castle as a settlement, which would most certainly be the case because people tended to live near the source of their fresh water. St Peter's Pool is known to have been filled by seven springs that would have provided an abundant supply for early settlers and is now one of the most ancient sites of an artesian well in the country and has figured prominently in the development of the town. Bourne Castle was the seat of the Saxon Lords of Bourne Manor, including Morcar, who fell with his followers at the Battle of Threekingham in 870; Oslac, who died in 960; Leofric, the benefactor of Croyland Abbey and afterwards of Hereward the Wake, the famous Saxon chieftain, on whose death it was given by William Rufus to Walter Fitzgilbert. But from the reign of Henry II until that of Edward III the manor was held by the Lords of Wake and Wilsford who are said to have occupied the castle which according to tradition was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell. But then the possibility of a Norman castle being built in Bourne emerges with accounts of the Conquest of England by William of Normandy, which had repercussions in all parts of the country. Most of Lincolnshire's 32 castles were built at strategic points by William during the years that followed the Conquest to subdue any possible revolts and to administer the substantial estates he had created. He took possession of Lincoln two years after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. There seems to have been little resistance and the king allowed twelve lawmen to retain their powers in the town and he took the precaution of building a castle to overawe the citizens.

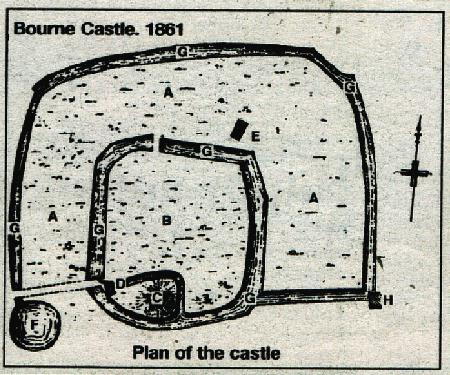

Stamford was treated in much the same way and a castle was also erected there, but the nearest to Bourne was at Castle Bytham, eight miles to the south west. Furthermore, a castle in Bourne and particularly one built or occupied by the Normans, would have been mentioned in the Domesday Book, the great land survey ordered by William in 1086, but there is no such reference. There was an outer moat enclosing eight acres, and an inner moat of one acre, inside which on a mount of earth cast up with men's hands, stood the castle, once the stronghold of the Wakes. Today, a maze of grassy mounds alone attests the site, amongst which the Bourn or Brunne gushes out in a strong clear stream. Other writers opposed to these theories have been quite sceptical about the entire existence of a castle in Bourne at any point in the town's history and after all there is nothing visible in the Wellhead Gardens that point indisputably to the remains of a castle apart from a few mounds and undulations in the grassy surface. The 16th century antiquarian John Leland called here while making a tour of the country between 1534 and 1543 and he found the castle greatly ruined with little but earthworks remaining. "There appere grete ditches, and the dungeon hil of an ancient castel agayne the west end of the priori, sumwhat distant from it as on the other side of the streate backwarde; it longidd to the Lord Wake, and much service of the Wake fe (family) is done to this castelle; and every feodarie knowith his station and place of service." During the Civil War period, a century later than Leland, there is also a brief reference to a castle in the parish registers saying: "Oct 11th, 1645, the garrison of Bourne castle began". This suggests that the castle was still in existence and consisting of much more than Leland's "grete ditches and dungeon hil" which leads us to wonder whether considerable repairs had been carried out to the building in the intervening century or that in 1645, a garrison of soldiers simply set up camp on the site where the castle was reputed to have once stood.

During the early 1960s, engineers from the electricity board had to dig a trench across the Wellhead Gardens and archaeologists accompanied by an historian inspected the work as it progressed. A little mediaeval pottery was unearthed, dating from the mid or late 13th century at the earliest, but the investigators stressed that this did not prove that the castle could not have been built before that date. A well-preserved wall that was obviously part of a mediaeval building was also revealed during the digging although it was thought that any earlier levels would not have been unearthed by this excavation. Further archaeological investigations were carried out during the laying of a pipeline across the Wellhead Gardens in October 2001 in an attempt to improve the flow along the Bourne Eau. The nine-inch water main ran from St Peter's Pool to the pond section in front of the Wellhead Cottage, a distance of 200 yards, and involved digging up the meadows where Bourne Castle is reputed to have stood and so an archaeologist was on hand to record any important finds. The investigation was carried out by Barry Martin from Archaeology Project Services which is part of Heritage Lincolnshire, who recorded items of pottery from Roman, Saxon and Norman times but, more importantly, he has also identified the foundations of masonry walls four feet thick running from east to west behind the Wellhead Cottage. These appeared to be the remains of a substantial building and could well have been part of the castle or perhaps a fortified manor house.

Nikolaus Pevsner, one of the most learned and stimulating writers on art in England during recent times, visited Bourne while compiling his survey of Lincolnshire in The Buildings of England, first published in 1964, and he not only accepted Bourne Castle as a fact but also dated it. His entry says: "To the south of the town lie the very extensive earthworks of an 11th century castle. It consisted of a motte and bailey, with at least two large outer enclosures. It had masonry defences, and there is a copious water supply for its ditches. Of all this little remains; the ditches are largely dry, the masonry has been removed, and the motte has almost entirely vanished - probably dug for gravel." It was a Roman station; it was a Saxon stronghold; it had a Norman abbey and a moated Norman castle. Behind West Street is the site of this once-famous castle, now little more than grassy mounds and traces of moats. The Romans may have had a fort here to guard their road and canal . . . but its heyday was as a castle of the Norman lords, the Wakes. There was Hugh, who married Baldwin Fitzgilbert's daughter, and later on Margaret de Wake, who married a Plantaganet, her daughter Joan marrying Edward the Black Prince and so becoming the mother of Richard the Second. The Wakes claimed descent from Hereward the Wake, who made a great stand in the last struggle against the Conqueror. The legends which have grown up around this hero make Bourne his birthplace, and Charles Kingsley made it the scene of his story. We know that Thomas de Wake entertained Edward the Third here, and we know that nothing but mounds and moats remained in the time of Elizabeth, though a tale persists that the castle was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell. The Norman castle is said to have been a massive keep with square towers, with a moat surrounding its low mound, and another moat enclosing the bailey covering eight acres. The moats were filled by Bourne's famous spring which comes to life here at a spot called Well Head or Peter's Pool. This glorious but highly inaccurate résumé is one of the reasons why so much about Bourne is misunderstood today because Arthur Mee's books about England's heritage were highly regarded when they were published in the years following the Second World War and were required reading by most schoolchildren. There were 41 volumes in the series, described as "A New Domesday Book of 10,000 Towns and Villages", and the books are still collected and treasured today and often quoted for their colour and detail which gives a picture of the English countryside as it has come down through the ages, a census of all that is enduring and worthy of record. But it is not necessarily accurate although extracts can still be found in many subsequent books and official guides and so the myths are perpetuated. It is therefore up to each of us to make our mind up about Bourne Castle.

REVISED AUGUST 2005 See also Bourne Castle - fact or fiction An enthusiast's appraisal The owners of Bourne Castle The Bourne Eau

Go to: Main Index |