|

Bourne Castle – fact or fiction? AN EXAMINATION OF THE EVIDENCE by REX NEEDLE

The controversy over the existence of

Bourne Castle surfaces perennially for although it is part of our

tradition, hard evidence has been practically non-existent and so the

argument has become a regular occurrence. As the site has never been properly excavated, folklore overshadows the

facts. There have been desultory attempts to discover what lies below the

surface but all have proved to be inconclusive.

The reputation of a traditional Bourne or Hereward’s Castle therefore

depends entirely on the enthusiasm of archaeologists and others anxious to

authenticate their beliefs but there have been no firm discoveries to

support the theory although there is sufficient documentation to disprove

it. It has not been established where the real Hereward met his end and it has been suggested that he died in France while another apocryphal account relates that he was killed by the Normans during a skirmish in Bourne Wood but in less than a hundred years the legend of Hereward was in full cry in the Estorie des Engles by Geoffrey Gaimar (circa 1140) and the Gesta Herewardii Saxonis or Deeds of Hereward the Saxon from around the same period. Songs were being sung about Hereward in the taverns and in the 13th century people were visiting a ruined wooden structure in the fens which became known as Hereward's Castle but interest soon died out as he was supplanted by another outlaw hero, Robin Hood, as a symbol of resistance to oppression. The foundations of the current thesis about the description of the castle were laid by John Leland (1502-1550), chaplain to Henry VIII and an enthusiastic antiquarian. Until his time, all ancient monuments were totally disregarded and in an attempt the redress this imbalance, the king commissioned him in 1533 to seek out England's antiquities by exploring the libraries of all cathedrals, abbeys, priories, colleges and other institutions where old records were stored. In this research, Leland spent over six years, from 1540 to 1546, travelling throughout England, visiting the remains of ancient buildings and monuments of every kind and on the completion of his work he presented the results to Henry, under the title of a New Year's Gift. In it, he says that the castle was "very greatly ruined with little but earthworks remaining". His description, the most telling challenge to the existence of a castle, is reproduced here verbatim: There appere grete ditches, and the dungeon hil of an auncient castel agayne the west end of the priorie, sumwhat distance from it as on the other side of the streate backwarde: it longidd to the Lord Wake, and much service to the Wake fe is done to this castelle; and every feodarie knowith his station and place of service. A further account appears in a history of Aveland published by John Moore in 1809, based on the manuscript of Peak, a gentleman traveller and antiquarian, writing about the towns in Kesteven in the late 17th century, and this description was far more imaginative and has been used as the basis of all future accounts: The castelle of Brunne ys a verrye ancyent portlie castelle scytewate neare Peterspoole, it contaynes the principal wardes. On the north side ys ye porter’s lodge, wch ys now reuinoose and in decaye by reasone ye floors of ye upper house ys decayed, and very necessarie to be repayred. The dungeon ys sett of a little moate with men’s handes, and for the moste parte as yt were square. It ys a fare and prattie buildings wth IV square toures. Rounde about ye same dungeon upon ye roofe of ye said toures, ys tryme walkes and a fare prospect of the Fenes. And in ye said dungeon is ye halle, chamberes and all other manner of houses of offices for ye lorde and his traine. The southe syde therof servethe for ye lordes and ladies lodginges; and underneighe them ys ye prisone, and wyne celler, wth ye shollorie. Over the moate yt surrounds ye castelle ys a fare drawe bridge,ye moate ys verie fresh and deipe. Ther ys also a fare parke belonging ye castelle. The 19th century and the growth of popular

reading brought a fresh wave of tales about historical characters, the

backgrounds drawn from the old chronicles that had been written down from

folklore and hearsay, what we call today the oral tradition, and these

thrilling stories added to the legend of Hereward and his castle. Among

them were Count Robert of Paris (1832) by Sir Walter Scott, Charles Macfarlane in The Camp of Refuge

(1844) together with A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens

(1852-54). In 1865 came the most popular of them all, Hereward the Wake by

Charles Kingsley, written while staying at the vicarage at Edenham, near

Bourne. All of these stories were further enhanced by Christopher Marlowe

in his highly colourful book Legends of the Fenland People (1926), an

exemplar of these romanticised tales, written in the tradition of the old

chroniclers, investing our hero with that unconquerable spirit of patriotism that

still pervades current thinking on the subject. The old days live again,

national unity, loyalty and betrayal, and we are hurried on by their

adventures, inspired by the undying hope of our brave hero for we are in Boy's

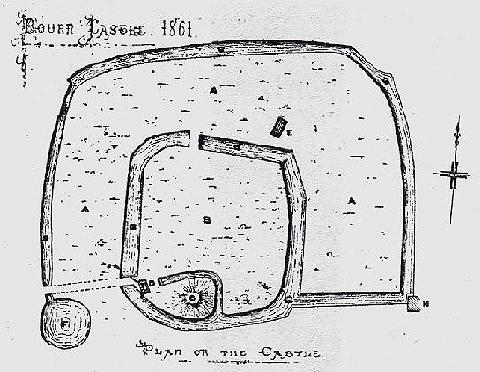

Own land and Bourne Castle is at its centre. Subsequent "excavations" cited, particularly by Lincolnshire Heritage, anxious to preserve its niche market and corresponding jobs, all financed with public money, were not in fact scientific examinations but merely a watching brief by one of their archaeologists whenever excavations took place in the Wellhead area. For instance, electrical cables were laid in 1960 when items of 13th century pottery were unearthed together with indications of a substantial stone structure but the location was recorded as being "within the castle grounds". In 1996, a similar examination purported to have uncovered "the remains of the castle's defensive moat" and a map was prepared showing how the castle was laid out, a document that bore an uncanny resemblance to the imaginative artist's impression from 1861. In 2001, we are told that "the most recent excavations at the site" uncovered one of the castle ramparts, a number of stone walls and the definite outline of a moat. "Four roughly parallel walls were also uncovered in the north east area of the castle compound as well as late Saxon pottery", claims Lincolnshire Heritage [Stamford Mercury, Friday 2nd September 2005]. This particular report interests me most because I happened to be present and there was no such occurrence. The facts of the matter are that in October of that year, a 200 yard pipeline was laid from St Peter's Pool to the Bourne Eau in that small pool near the Shippon Barn where the mallard and moorhen gather. The work was carried out by contractors acting for the Black Sluice Internal Drainage Board, instructed by Bourne United Charities that administer the Wellhead Gardens, with the object of regulating the water supply from the pool into the river during dry spells and to disperse the build up of silt and mud that had been hampering the flow. The only excavations carried out were by the small mechanical digger that ploughed a narrow furrow, perhaps 18" wide, between the two points to allow the sections of pipes to be dropped in and joined up. An archaeologist was in attendance on some days and I spoke to him frequently (as I did to the contractors who consisted of one man and a lad) and although he was busy with his clipboard most days, it is difficult to reconcile any discoveries he might have made with the report in the Stamford Mercury on 2nd September 2005. The odd thing is that if this "excavation" was of such tremendous importance, why was it not reported by the local newspapers at the time, yet not a line was used by any of them. The only account of the occurrence appeared in my Diary of Saturday 13th October 2001 that is still available in this archive. Such is the stuff of local history. The existence of a castle on this spot therefore relies on assumption and

opinion instead of evidence and excavation. A few remnants of masonry and

pottery do not establish the authenticity of an ancient monument. There

may be stonework beneath the surface of the Wellhead Gardens but it is

more likely to be that from dwellings and other buildings which comprised

the settlement that sprang up around the source of water at St Peter's

Pool rather than a battlemented fortification similar to those we now see in

Disneyland.

NOTE: A shorter version of this article

appeared in The Local newspaper WRITTEN SEPTEMBER 2005 See also A enthusiast's appraisal Hereward the Wake and the barony of Bourne Return to

Go to: Main Index Villages Index

|