The

Car Dyke

|

|

|

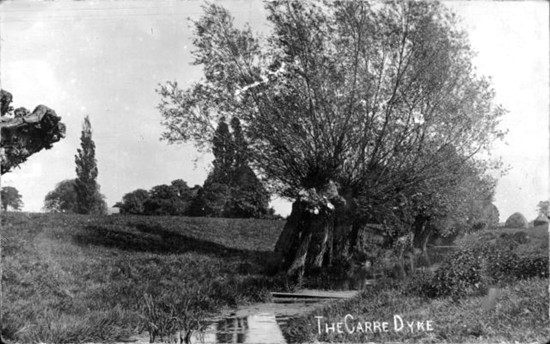

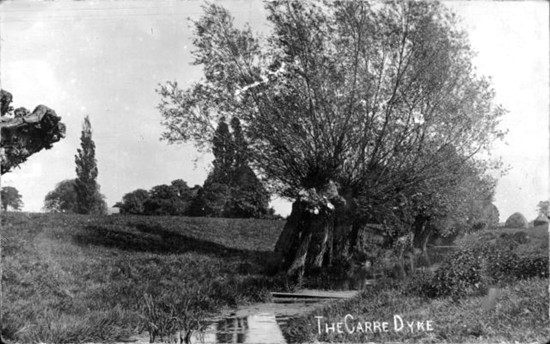

This is the Car

Dyke at Dunsby Fen, four miles north of Bourne, and although an

attractive fenland waterway today, it shows little of its

importance in the

communication and transport system of Roman

Britain |

The waterways of fenland have been used by its inhabitants for centuries, even as far back as the Bronze Age which is usually dated in Europe from 2000 to 500 BC. The early settlers travelled these parts by boat on their expeditions in search of fish and fowl to feed their families and for reeds to thatch their houses and turf to fuel their fires. Their boats were hewn from the trunks of oak trees and many have been found in South Lincolnshire. One of them which was recovered from Deeping Fen was 46 feet long with a maximum beam of 5 ft 8 in and had a ribbed floor and an external keel cut out of the solid wood which demonstrated that these people were no mean sailors.

There is however no evidence that the early inhabitants of the fens used these waterways for anything more than domestic purposes but with the coming of the Romans 2,000 years ago, all this changed and the invaders made a determined effort to improve their lines of communication. Their most ambitious project was the Car Dyke, a watercourse of 75 miles in length, starting at Waterbeach in Cambridgeshire then crossing the River Welland and entering Lincolnshire at Deeping St James. From here, it skirted the western limits of the fens and joined the River Witham at Torksey

below Lincoln, and so extended for a distance of 56 miles through Lincolnshire.

|

AN AERIAL VIEW OF THE GREAT WATERWAY

Car Dyke photographed on 22nd July 2003. The

waterway was originally thought to be a Roman canal but is now

believed to be part of a fen drainage system from 1st or 2nd AD. It

follows a sinuous course down the south side of the Witham valley,

surviving as earthworks for long stretches, but where levelled is

also visible as crop marks. The central ditch has substantial banks

flanking it, which possibly acted as flood defences.

|

|

This great channel known as the Car Dyke was probably constructed early in the second century AD, was built purely for drainage purposes to produce more fertile land for corn crops but the most popular theory that transport was the main aim, opening up the entire county to the movement of heavy goods, persists and the evidence of population growth along its banks which would have occurred in this instance is too strong for it to be seriously disputed. Indeed, the remains of forts, placed for its protection, have been discovered in past years at Billingborough, Garwick (Heckington), Walcot, Linwood and Washingborough and it is doubtful that such measures would have been taken had the waterway been intended for purely agricultural rather than military purposes.

It has been recognised since the 18th century as an important feature of the ancient landscape, possibly the second longest Roman monument after Hadrian's Wall, yet very little is known about it and it has even been suggested that it might have been a Roman Imperial estate boundary. It was first described as a canal for the trade and transport of goods by William Stukeley (1687-1765), the distinguished antiquary from Holbeach in Lincolnshire who carried out extensive fieldwork at Stonehenge and Avebury and whose account of his travels around Britain was published in his

Itinerarium Curiosum. Since then, the Car Dyke has been recognised as having an equally important role as a catchwater drain, diverting the east flowing waters away from the fens and although all sources agree on a Roman date for this feature, no one has demonstrated any evidence for it. Much is speculation and little is proven.

Extract from A Dictionary of Lincolnshire Place Names by

Kenneth Cameron

The name Car Dyke, or Kárr's ditch, was originally

Karesdic, derived from Kárr, meaning a low place or fen and the Old Norse

dík and by the early 12th century had become Karisdik, then Carisdik and by 1259 it was known as

Cardik and this has led us to the Car Dyke we know today although less frequently it is spelt as Carr Dyke. A contemporary canal, the 11-mile long Foss Dyke, linked the rivers Witham and Trent and with further navigable stretches of waterway east of Peterborough along a stretch of the River Ouse known as the Old West River and to the River Cam at Waterbeach in Cambridgeshire, the system provided a lengthy and continuous chain for inland water transport from Cambridge to York. By this means therefore, supplies could be carried by barge from the fens to Lincoln and then as the army moved north, the system was extended to York by means of the Foss Dyke, the River Trent, the Humber and the Yorkshire Ouse.

This transport system may have been used to carry supplies by barge from East Anglia to the Roman armies in the north, the main cargoes being corn, wool for uniforms, leather for tents and shields and provisions such as salted meat. The barges may then have come back laden with coal and building materials and the pottery made in the Castor area near Peterborough, an important Roman manufacturing centre known as

Durobrivae, must have been distributed in both directions and there is some evidence of a dock or loading point for boats on a bend in the River Nene near Castor. Similarly, a substantial stone wall over 20 feet long was found outside the colonia, or settlement, at Lincoln near the River Witham which could have been a quay well placed for traffic along the Car Dyke. This must have been the pattern all over the country wherever there were waterways deep enough to allow the passage of barges and other canals of varying sizes probably still await discovery, especially in the fens.

|

The Car Dyke runs through

Dyke which is how it gets its name. Henry Penn, the famous 18th century bell-founder,

cast one of the bells for Lincoln Cathedral at his foundry in Peterborough in 1717 and sent it to Lincoln on a raft, passing through this village,

thus indicating that the waterway was still navigable more than 1,500 years after it was built.

|

|

A study of the canals built by the Romans in France and Germany, especially at the mouth of the Rhine, indicate that work of a similar character was probably organised by their army in Britain which resulted in the Car Dyke. Excavations carried out in 1949 along the eight-mile stretch between the rivers Cam and Ouse in Cambridgeshire showed it to be about 28 feet wide and flat bottomed. The sides sloped outwards to give a width of about 45 feet at ground level and it was about seven feet deep. These measurements compare well with those of modern barge canals. Severe fen flooding in 1947 brought water back to the Car Dyke and gave some idea of its appearance in the Roman period.

However, there is no doubt that the Car Dyke also functioned as a catch-water drain, carrying off the water from the numerous high land brooks and streams from the west and although this strategic planning soon fell into disrepair in the fifth century once the Roman administration ceased, it did begin the long process of draining the fens. This project continued in various stages, through the Middle Ages with the establishment of the Commission of Sewers to oversee the upkeep of embankments and the cleaning of watercourses, the piecemeal improvements of the 16th and 17th centuries, major work during the 19th century, particularly in 1846 when a section of the dyke north of Haconby was scoured out and deepened to improve drainage, and thence into modern times. This important waterway ran through the Bourne area and a branch canal between Bourne and Morton

still exists today but can only be seen from the air when the field crops are at a stage which make its outline visible

although it has shown evidence of soak ditches parallel to the canal to take water from the field ditches and discharge it into the canal.

|

|

|

|

The Car Dyke pictured east of Morton village |

The Car Dyke and the Foss Dyke are the only canals in the country from this period and they provide evidence of the importance of the area to the economy of Britain during Roman rule. The Car Dyke was then a busy waterway and it is certain that farmsteads and riverside settlements sprang up along its banks and have since grown into the villages we know today.

The waterway gradually declined and by the end of the 19th century, it was in a

poor state. The Stamford Mercury reported on Friday 12th May 1899:

"It is reputed to be one of the oldest canals in Europe yet it has suffered

the fate of many former prosperous and busy waterways in England and has, by

centuries of neglect, been allowed to degenerate to the miserable dimensions and

condition of a ditch."

Much of the dyke is now silted up and disused although some of the best remaining stretches can

still be seen in the Bourne area where farmers have kept it in good order for

drainage and irrigation purposes, from the significantly named hamlet of Dyke and Car Dyke Farm in the neighbouring parish of Morton, to Thurlby further south but then, as the fens proper begin, it is often difficult to trace.

The Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire has an ongoing research project into the origins of the Car Dyke and what the future holds but their assessment of its current state is not good. They report that the waterway still plays a role in modern farm drainage and survives in various states of preservation along its length and although ten sections have been protected as scheduled ancient monuments its future is still threatened by commercial development and intensive agricultural practices. Their aim is to stimulate public interest in the waterway both locally and regionally and to improve the access to and awareness of one of Lincolnshire's major Romano-British monuments.

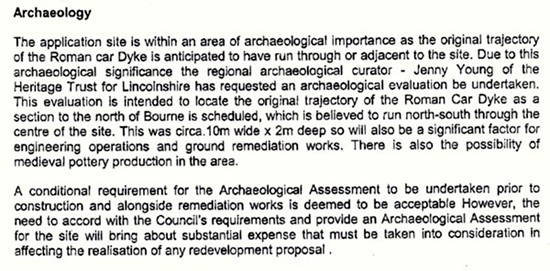

The trust is particularly anxious to find out

more about the Car Dyke whenever land adjacent to the watercourse is redeveloped

and has been given permission to make an archaeological evaluation of the site

currently occupied by the Rainbow supermarket and the Raymond Mays garage

premises in Bourne, an area between Manning Road and Spalding Road extending to

over five acres which is destined to be used for new housing, although the

scheme is currently on hold because of the economic crisis. The site is

recognised as being of archaeological importance because the original trajectory

of the waterway is thought to have run through it or nearby and a search in

advance of building work is likely to establish further information about it as

well as revealing artefacts from a mediaeval pottery thought to have been

operating in the vicinity.

Extract from the planning application in March 2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

top photograph shows the Car Dyke near Bourne in 1909 and again in

1910 (middle), this time photographed by Ashby Swift. The bottom

picture dates from circa 1920 and shows Eastgate with Bedehouse Bank on the left

when the waterway was much wider. The picture

below was taken along the same stretch in 2008. The footpath

alongside remains open to the public and many residents whose houses

back on to the waterway make a feature of of the bank and keep it

tidy but it is not well maintained by Anglian Water and is choked

with weeds and rubbish in many places as can be seen from the bottom

photographs. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Car Dyke is cleared of weeds every summer

by the Environment Agency. Some of this work is done by mechanical

dredger but the longer stretches such as here in Blackthorn Way,

Bourne, have to be cleared by hand, a laborious and dirty job that

is made more difficult in wet weather when weed has proliferated.

The two workmen pictured here in July 2012 said that they were

rather startled to find many large eels as they carried out their

work. |

|

Extract from The Beauty of Lincolnshire published

1807

(Spelling and grammar as written)

A great work of this county, generally attributed to the Romans, is the

CAR-DYKE, a large canal or drain, which extends from the River Welland, on

the southern side of the county, to the River Witham, near Lincoln. Its

channel, for nearly the whole of this course, an extent of about forty

miles, (Dr Stukeley says fifty) is sixty feet in width, and has on each

side a broad flat bank. The Doctor at first ascribed the origin of this

great work to Catus Decianus, the procurator in Nero’s time; and supposed

that his name was preserved in the appellation of places, &c. in the

vicinity of the Dyke. Those of Catesbridge, Catwick, Catsgrove,

Catley,

and Catthorpe, he adduced in support of his hypothesis; but having

afterwards devoted some time and attention to the life of Carausius, the

Doctor fancied he recognised part of the name of his hero in that of the

present work. Thus some authors trifle with themselves and their readers

by useless, and often puerile etymologies. Salmon, in the "New Survey of

England,” says, that “Cardyke signifies no more than fen-dyke. The fens of Ankholm-level, are called

Carrs.” Doctor Stukeley also admits that Car and

Pen are nearly synonimous words, and are “used in this country to signify

watery, boggy places.” Cŕr, in the British language, is applied to raft,

sledge &c. vehicles of carriage, This great canal preserves a level, but

rather meandering course, along the eastern side of the high grounds,

which extend in an irregular chain up the centre of the county, from

Stamford to Lincoln. It thus receives, from the hills, all the draining

and flowing waters, which take an easterly course, and which, but for this

Catchwater drain, as now appropriately called, would serve to inundate the

Fens. Several Roman coins have been found on the banks of this dyke.

NOTE: Dr William Stukeley

(1687-1765) was an English antiquary and one of the founders of field

archaeology, who pioneered the investigation of Stonehenge. He was born at

Holbeach in Lincolnshire and studied medicine at Cambridge University but

while still a student he began making topographical and architectural

drawings as well as sketches of historical artefacts. He continued with

this alongside his career as a doctor, and published the results of his

travels around Britain in Itinerarium Curiosum in 1724, a valuable record

of monuments, buildings and towns before they were subjected to the

ravages of the agricultural and industrial revolutions. He deplored the

destruction of monuments and realised the importance of recording

accurately what he saw as a way of preserving information about the past.

In 1718 he became the first secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of

London. His activities in the field included excavations at Stonehenge and

Avebury, the results of which were published in two books in 1740 and

1743. Stukeley mistakenly attributed them to the Druids. He was fascinated

by the Druids and developed elaborate and fanciful descriptions of their

practices and beliefs. However, he was also the first to recognise the

alignment of Stonehenge on the solstices, and saw the value of exploring

the wider relationship between monuments and putting them into their

landscape context. Stukeley's interests were wide and included other

aspects of British history, including the story of Robin Hood. He also

wrote music for the flute and produced treatises on earthquakes and

medical subjects. In 1730, he changed career and was ordained as vicar of

All Saints Church at Stamford, Lincolnshire. He died in London on 3 March

1765. During his lifetime he was a friend of Isaac Newton and wrote a

memoir of his life (1752). |

See also Walking

the Car Dyke Dyke village

Go to:

Main Index

|