|

The

workhouse

The workhouse has earned its place in English

social history as the last resort for the poor and destitute, immortalised by Charles Dickens in his novel Oliver Twist that was written against the background of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 which ended supplemental dole to the impoverished and forced husbands, wives and children into separate institutions in the name of utilitarian efficiency.

The welfare and relief of the poor had always posed a problem for society and by the early 19th century it was clear that the existing system needed drastic revision. The overseers of the poor in each parish were responsible for giving relief to deserving cases but the burden on the rates was becoming heavy and the relatively easy terms on which men without an adequate wage could get financial help from public funds was being regularly abused. The government therefore decided to impose a more rigid

procedure and the new legislation decreed that able-bodied men who could find no work had no option but to enter the workhouse, taking their families with

them although in some cases, children were boarded out with foster

parents.

|

The Bourne workhouse

was built in St Peter's Road in 1836 at a cost of £5,350 with

room for 300 paupers. The premises were converted for use as a

mental hospital in 1930 but closed down 70 years later and in

2001, the building was demolished and the site is now used as a

car park for the printing firm Warners Midlands plc. |

This was the main principle of the act that also required parishes to be grouped together as unions with a workhouse for each.

Bourne Poor Law Union was formed on 25th November 1835 and to supervise the workhouse and the local administration of the new law, a Board of Guardians was elected from the district and the government,

a total of 44 in number and representing 37 constituent parishes, and they

lost no time

in establishing the system that became operative before the end of

1836.

The town already possessed a workhouse

that stood in North Street near the junction with Burghley Street which

was then called Workhouse Road. This institution was let annually together

with a small parcel of land and run by an officer who was appointed by the

churchwardens and the Overseers of the Poor at one of their regular vestry

meetings and a public notice which appeared in the Stamford Mercury

on Friday 26th February 1830 describes the arrangement:

The parishioners of Bourne are

desirous to contract with a proper person to undertake the maintenance and

management of the poor at a certain rate per head per week for one year

from 25th March next. The contractor would also be accommodated with free

occupation of five acres of good meadow land and the pasturage of two cows

upon the droves. Any person who can be properly recommended and can give

the security required by Act or Parliament for the due performance of his

contract may send proposals to the churchwardens or Overseers of the Poor,

or deliver the same at a vestry to be holden at the parish church on

Thursday 11th March at 3 o'clock.

This workhouse was too small to cater for

the new legislation and so a new building was planned at the end of St

Peter's Road. The 37 parishes and townships covered by the Bourne Union

extended to over 106,934 acres of land and in 1851 included 22,362

inhabitants. The total average annual expenditure of the parishes during

the three years preceding its formation was £8,506. In 1838, their total

expenditure was only £4,256 but in 1855 it amounted to £8,965.

The

workhouse was designed by Bryan Browning, the architect responsible for

the Town Hall at Bourne (1821) and the House of Correction at Folkingham

(1825), and was

built in 1836 at a cost of £5,350, a substantial building, the

bricks being manufactured locally, with a blue slated roof and designed in

the shape of a crucifix. The height was approximately 40 feet with a main

entrance facing south and corridors leading to the east, north and west

wings with three floors throughout the main building, the entire property

standing in two acres of grounds to which a variety of extensions

and outbuildings were added over the years. The building provided

accommodation for 300 paupers but was rarely

full because admission was not encouraged by members of the Board of

Guardians who met every Thursday to determine policy.

|

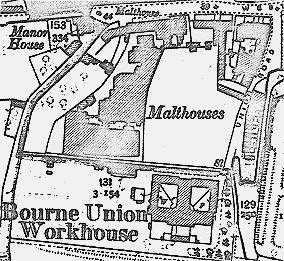

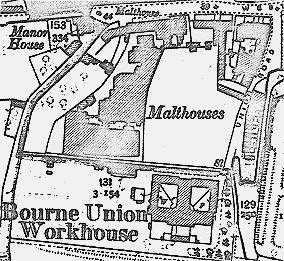

The location of the workhouse from the

Ordnance Survey of

1903. The name "workhouse" was subsequently changed because

of

the stigma attached to being an inmate to the

Bourne Public Service Institution and then to Wellhead House before

becoming St Peter's Hospital, a building that was demolished in 2001

and subsequently developed by Warners Midlands plc. |

|

They enforced a strict regime in a bid

to encourage the poor to seek employment rather than live in such grim

and uncongenial surroundings, usually by providing outdoor relief or

assistance at home to avoid their admission to the workhouse. In 1841,

there were only 84 inmates and 178 in 1851 when the census was taken. In

1881, the workhouse had a total of 123 officers and inmates and the

guardians were meeting once a week to perform their duties.

Their primary work was the supervision of

the smooth running of the workhouse and the appointment of the staff to

implement a daily routine including a master and matron, usually a husband

and wife team approved by the board, a medical officer, chaplain,

a schoolmaster to assist with the welfare of the inmates

who were not generally treated with much sympathy. In December 1842, the

guardians decided to save money by uniting the office of master with that

of schoolmaster at a salary of £60 a year which meant that one man was

doing both jobs but for only one salary. However, as the number of inmates

increased, further teaching staff were required and a schoolmistress was

appointed in 1854.

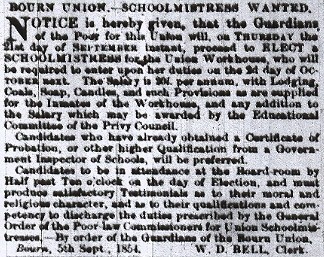

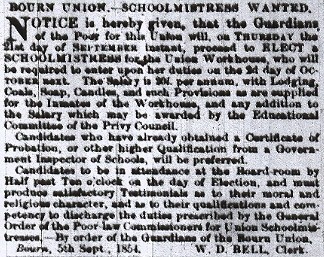

|

|

Public notice advertising for a

schoolmistress

at the workhouse which

appeared in the Stamford

Mercury on Friday 8th September 1854, signed

by the clerk to the

Guardians, Mr William Bell. |

Spiritual instruction was highly regarded

by the Board of Guardians who insisted that the inmates should attend

services at the Abbey Church on Sundays although this was not always

successful because there was insufficient room. The Grantham Journal

reported on Saturday 19th February 1859 that during one of their

inspections of the workhouse, the master was interrogated about their

attendance, it having been the custom for many years for the male and

female adults to go on alternate Sundays as accommodation was only

provided in the church for about thirty of them at any one time and it was

decided to meet with the churchwardens in an attempt to make more space

available. Sunday services on the premises were eventually considered to

be a more satisfactory solution and in January 1870, the Board of Guardians

advertised for a chaplain to the workhouse who was "required to perform

all the duties of the office for a salary of £40 per annum".

A man was also employed as porter and

shoemaker and a newspaper advertisement from June 1870 said that the post

would be suitable for "a stout, healthy and active single man of sober and

industrious habits who was required to reside in the workhouse to make and

mend shoes and to instruct as many of the boys as may be required in

making and mending shoes for the use of the inmates as well as to perform

his duties as porter. Salary £26 beside the usual rations and a suit of

clothes."

The 1834 Act produced a system which swiftly reduced poor relief.

Productive work was not encouraged, rules were strict and the official

policy of economy left no room for luxuries. An expenditure sheet from the

Bourne Union for the quarter ending 24th September 1837 gives details of

how it was working soon after inception. During the period, indoor relief

was given to 126 people (43 males, 21 females and 62 children), but

outdoor relief was granted to a far greater number, namely 934 cases.

Thus, a total of 1,060 paupers in Bourne had been dealt with during the

period although not all of those given indoor relief actually lived in the

workhouse, the number including vagrants and other causal poor who had

arrived in the town and perhaps only received a night's lodging.

Expenditure on paupers who were actually

maintained in the workhouse was by no means lavish, amounting to 5p per

head per day in today's money, and that included clothing and food. The

total expenditure for the quarter under review was £923 9s. 5d. and at

this rate, the annual outlay could not have exceeded £4,000. By contrast,

the average annual expenditure immediately prior to the formation of the

Union had been £8,506, thus the new Poor Law had practically halved the

cost of poor relief for the Bourne area.

There was a great resistance to entering the workhouse or even

accepting relief from the parish and some who could not face the stigma

took drastic action, as in this news report from the Stamford Mercury

on Friday 12th May 1871:

On Monday morning last, a report was circulated

at Baston that John Newcomb, 77 years old, had attempted suicide by

cutting his throat with a large pocket knife. He has been ill for several

months and the fear of having to go to the parish for relief after his

sick pay from the club is discontinued has preyed upon his mind, it is

thought, and caused him to commit the rash act. He is under medical

attendance and may probably recover.

Nevertheless, poverty was so widespread that overcrowding became a problem

which was exacerbated by the number of tramps seeking an overnight stay. A

report from the workhouse master, Alfred Yates, to the Board of Guardians

on 29th April 1892, said that there was insufficient accommodation for

male vagrants. Upon several occasions, the female ward and the two

receiving wards had been occupied by men during the night. The board

decided that despite the situation, the master should take in as many

vagrants as he could accommodate and if there was insufficient room, then

they should be given tickets to enable them seek lodgings in the town.

The strict workhouse regime was maintained

at all times although there was an improvement in the food on special

occasions including Christmas when meals were provided to reflect the

festive season although these treats could be withheld if there was

insufficient money to pay for them. In 1841, for instance, economies were

enforced because of unexpected expenditure and the Board of Guardians

reported at their meeting on December 29th when they met to pay their

quarterly accounts: "The enormous increase of vagrants seeking a night's

refuge in the house was the subject of some remarks, as was also the

pinching economy of the Poor Law Commissioners in preventing the Guardians

from changing the dietary on Christmas Day, unless at their own expense."

One special occasion when inmates were

given treats was the royal wedding of the Duke of York and Princess Mary

in the Chapel Royal at St James' Palace in London on 7th July 1893 and the

Board of Guardians decided that by way of celebration, instead of

receiving their usual oatmeal and gruel, the inmates would be served with

a breakfast of tea, coffee, cocoa and bread and butter, a meat dinner and

a pint of beer for the men and a half a pint for the women, with bread and

butter and plum cake for their tea. The men would also be given an ounce

of tobacco each. The workhouse master, Mr Alfred Yates, assured the board

that such provisions would be more than welcome because he did not think

there were any teetotallers among the inmates although the women preferred

tea to beer.

There

were also gifts to the inmates from the local gentry and on 11th August

1874, eighty of them were given an afternoon picnic in Bourne Wood by

Baroness Willoughby, from Grimsthorpe Castle, and in the evening they were

entertained by the Bourne Drum and Fife Band, returning home about 9 pm,

"thoroughly pleased with the day's treat", according to the Stamford

Mercury. There was more generosity in October 1898 when

Sir John Lawrance, of Dunsby Hall, sent 10 braces of partridges from one of

his shoots to be cooked for their dinner.

In

1895, the Board of Guardians decided at their fortnightly meeting that the

old men in the workhouse should be allowed an ounce of tobacco a week,

jokingly referred to by members as "the fragrant weed". Tenders

for the supply of the tobacco were considered, the highest price being 3s.

6d. per lb. (16 oz.), and two firms tendered at this figure, one sample

being light and and the other dark. The samples were carefully examined by

the guardians and a most amusing discussion took place, as reported by the

Stamford Mercury on Friday 11th October under the heading "The

Pauper's Pipe", which reveals the patronising attitude they had

towards the workhouse inmates:

One

of the guardians urged his colleagues "to let them have it good"

on the grounds that it was the only comfort the old men had and that the

tobacco was worth its money if only for keeping the moths out of the

inmates' clothes. (Laughter). The chairman: "They like it strong,

gentlemen. They have been used to it all their lives." A proposition

was then made that the dark sample be accepted on the grounds that it was

"strong and full of juice". (Laughter). An amendment was moved

in favour of the light sample. Five voted on either side and the chairman

was then called upon to give a casting vote. He first examined the samples

and then said he should decide in favour of that which was "strong

and full of juice". The 3s. 6d. tender for dark tobacco was

accordingly accepted.

The

decision by the guardians to allow men over 60 years of age an ounce of

tobacco a week subsequently received a great deal of favourable press

coverage, both in London and the provinces, because, as the Stamford

Mercury reported, "only two other workhouses in the country, one

in Cornwall and another in the north of Scotland, have hitherto granted

the aged paupers the privilege of the pipe".

Conditions

at the workhouse improved slowly with the times and towards the end of the

19th century, it became necessary to appoint a full time nurse to

supervise medical care among the inmates. The situation was causing

particular concern in July 1898 during a visit by Mr H Stevens, the Local

Government Board Inspector, who found two men in the sick ward under the

care of another inmate. He told the Board of Guardians that an experienced

nurse was absolutely necessary and the Medical Officer of Health, Dr James

Watson Burdwood, was instructed to appoint one immediately but in return, he

insisted on improvements to the sick ward which he said was in a most

unsatisfactory state and his wishes were subsequently carried out.

In 1863, the name of the institution was changed from the Bourne Union

Workhouse to Waterloo Square in an attempt to remove the stigma attached

to the original address, especially among unmarried mothers who often gave

birth there. Birth certificates from the early 19th century reveal that

the girls were usually illiterate, having made their mark on the

documentation because they could not write, and no fathers were named, as

was the custom of the time. Death certificates were also sparse in detail,

"reason for death unknown" being a frequent entry although one from that

period states that an inmate "died by a visitation from God and cramp of

the stomach".

Apart

from providing for the poor of the parish, the workhouse also catered for

tramps passing through the district and who received lodging and a meal of

bread and gruel for perhaps one or two nights in return for some menial work such as chopping wood or sweeping floors.

These vagrants had been known to cause trouble, and even to bring lice

into the workhouse, and as a result, the Guardians decided on 6th February

1868, that everyone should be searched and given a bath before being admitted.

The rules governing this occasional

hospitality were strictly enforced and the Grantham Journal

reported on Saturday 6th March 1875 that "on Tuesday last, a vagrant who

gave the name of James Hopkins was sentenced to seven days' imprisonment

by the magistrates for refusing to perform his task in the workhouse. The

prisoner had been taken in for the night and was required to pick a

quantity of oakum before leaving in the morning. This he neglected to do,

pleading ill health, but he was examined by Dr J H Ashworth who certified

to the contrary."

* Oakum is a

preparation of tarred fibre used in shipbuilding for packing the joints of

timbers in wooden vessels and the deck planking of iron and steel ships,

as well as cast iron pipe plumbing applications. It was at one time

recycled from old tarry ropes and cordage which were painstakingly

unravelled and taken apart into fibre, the task of picking and preparation

being a common penal occupation in prisons and workhouses.

Tramps were a familiar sight on the roads of Britain after the First World

War, many of them wearing their campaign medals, and an indication of the

numbers seeking help can be found in the reports of the Board of Guardians

from that time.

During a two-week period in April 1926 for instance, 323 vagrants had been

given assistance with 40 seeking food and accommodation on one night

alone. This stretched the resources of the workhouse to the limit and as a

result of the high numbers, the board ruled that they could stay for only

one night and must move on next morning.

|

|

|

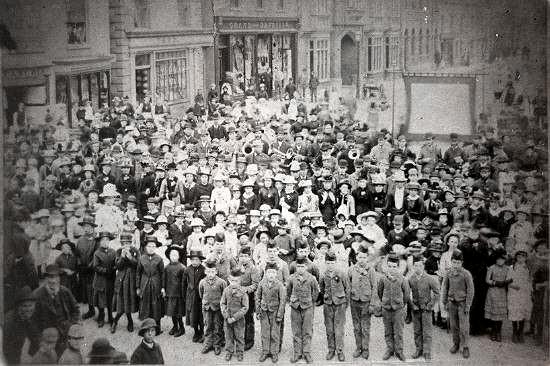

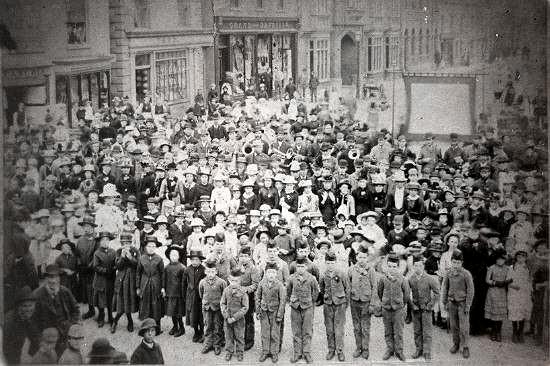

Children from the workhouse in Bourne are

pictured in the foreground, all dressed in their distinctive

uniforms, taking part in one of the public gatherings in the market

place, circa 1900, and below, the Board of

Guardians pictured outside the workhouse in Bourne after one of

their fortnightly meetings circa 1905. |

|

|

The social disgrace of the

workhouse system remained well into the 20th century and today it is remembered in folklore and literature as a place synonymous with hunger and poverty. Improvements in social conditions brought about its gradual decline and by 1905, there were only eight officials in charge of 87 inmates and the guardians were meeting only once a fortnight. Other charities sprang up, providing relief for the poor and in 1908, a Royal Commission tried to

end the stigma of poverty with the establishment of a Public Assistance Authority and the creation of new social services in the years following the First World War meant that the days of institutional

assistance were over.

In

1930, the workhouse became known as Bourne Public Assistance Institution

and was also known as Wellhead House, becoming a hospital for the mentally

handicapped and the main building was re-designed for its new role.

| The Bourne Union covered the following parishes and populations

(1851):

|

|

Bourne district:

Haconby

454

Morton

938

Edenham

670

Bourne

3,717

Witham-on-the-Hill

298

Manthorpe

106

Toft & Lound

231

Carlby

349

Thurlby

799

Corby district:

Careby 108

Little Bytham 573

Castle Bytham, Holywell

Aunby & Counthorpe 131

Creeton 103

Swayfield 383

Swinstead 490

Corby 258

Irnham, Hawthorpe

& Bulby 174 |

Deeping district:

Baston

863

Langtoft

701

Market Deeping

1,294

Deeping St James

1,849

Deeping Fen

1,098

Aslackby district:

Aslackby

492

Kirkby Underwood

185

Folkingham

763

Laughton

69

Horbling

550

Billingborough

1,048

Sempringham

49

Birthorpe

56

Pointon

490

Dowsby

215

Rippingale

661

Dunsby

203

TOTAL

20,368

|

|

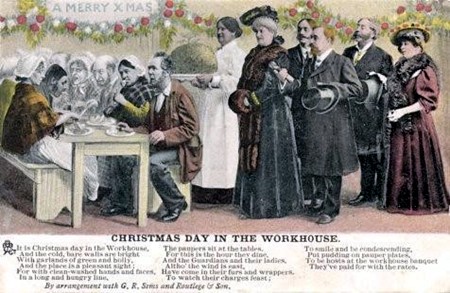

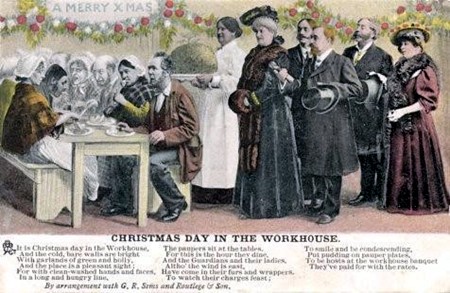

CHRISTMAS

DAY IN THE WORKHOUSE

A popular dramatic monologue performed at

smoking concerts and in the music halls of Victorian England was a

heart rending account of poverty among the working classes called

Christmas Day in the workhouse. It was written in 1879 by George

Robert Sims as a criticism of the harsh conditions in workhouses

that had been established throughout the country.

Sims (1847-1922) was a playwright and poet whose work raised

public awareness of the suffering poor to such a level that he was

appointed to study social conditions in deprived areas and to give

evidence to a royal commission on working class housing.

Workhouse inmates enjoyed occasional luxuries usually paid for by

wealthy townspeople who often dropped in on Christmas Day to see

how their money was being spent, to receive the thanks of the

inmates and to ensure that they appreciated what they had been

given, and it is this image that has been caught so evocatively by

George Sims in his monologue, a picture of wealth and privilege

against a background of poverty and ill-luck. We have these

examples from the pages of the Stamford Mercury and the

Grantham Journal.

The inmates of the

Bourne Union-house have been variously entertained during the

festive season. On Christmas Day they had the usual treat of roast

beef and plum pudding, &c; and on New Year's Day, by the

liberality of Lord Aveland, they had a further treat; and on

Monday last an entertainment and a Christmas tree were supplied

them, the Bourne Amateur Minstrels having given towards it £1 4s.,

part of the profits realised by their entertainment at the Corn

Exchange on the 20th ult. During the evening the amateurs repeated

the entertainment before the inmates, who were highly gratified

with the performances and the presents from the Christmas tree. On

the motion of Mr Jenner, seconded by the Rev George Parkinson, a

vote of thanks was accorded to the Bourne Amateur Minstrels. The

whole affair was a successful and pleasant one. - Friday 11th

January 1878.

CHRISTMAS

AT THE WORKHOUSE: The inmates of the Union Workhouse had their

share in the general festivity of the season, being provided with

a bountiful dinner of roast beef and plum pudding, by order of the

Guardians, in addition to which gifts of tea, tobacco and fruit

were provided for each inmate through the kind liberality of Dr

and Mrs Watson Burdwood. The bounty and open-handedness that is

supposed to prevail at this happy season could not well find a

better outlet than in providing at least one joyful day for those

whose lives, however kind the officials in charge may be, must be

one of cheerless monotony. The heads of the various religious

denominations in the town do what they can to relieve this

monotony for the children by inviting them to the annual school

treats in the summer; through the kindness of Lord Willoughby they

have also had a day at the seaside. We are glad that there are

kind friends also to think of, and provide for, year by year, the

happiness of the older inmates who doubtless enjoy weeks

beforehand the anticipation of the treat for them on Christmas

Day. - Saturday 5th January 1889.

CHRISTMAS TIDE;

On Sunday, at the Abbey Church and all the Free Churches, Christmas services were held and appropriate hymns were included in the musical portion of the service. On Christmas-day there were celebrations of the holy communion at the Abbey Church. At Matins the preacher was Rev

E H Fletcher. At the Wesleyan Church there was the usual Free Church Christmas morning service, which was conducted by Rev

J A Halfpenny, Mr W Goy presided at the organ, and the collection was on behalf of the Butterfield Hospital. The inmates of Well Head House had a fine time on Christmas-day. The various rooms had been tastefully decorated and presented a cheerful appearance. The special diet included pork-pie for breakfast; roast beef, roast pork, hare, and plum pudding for dinner; plum cake and jam for tea. Amongst those present at the dinner were Rev

J A Halfpenny (religious instructor). Major C W Bell (clerk), Mr W Kelby (vice-chairman), Rev

J Carvath, Miss Bell (Guardian), Dr and Mrs Galletly, Mrs C W Bell, and Mr

W H Smith. The children were regaled with a Christmas-tree and in addition there was a considerable quantity of toys for the children, sweets for the women, and tobacco for the men.

- Friday 28th December 1923.

CHRISTMAS SERVICE AT THE

WORKHOUSE: The usual weekly service conducted by the Religious Instructor (Rev

J A Halfpenny) at Well Head House took the form of a Christmas service on Friday evening. The members of the congregational Young People's Fellowship attended, and sang Christmas hymns, which were accompanied by Mrs. Halfpenny. The visitors provided tobacco for the men and sweets for the women and children. At the conclusion of the ordinary service in the Board-room, the visitors went to the sick wards, and rendered the Christmas hymns to the inmates of those wards. The thanks of the inmates were voiced by Mrs. Hancock, the matron.

- Friday 28th December 1923.

LITTLE BOY'S THANKS: At the fortnightly meeting of the Board of Guardians on Thursday, the House Committee reported that there were 82 inmates in the

workhouse, and that during the fortnight there had been 147 vagrants relieved. The House Committee recommended that letters of thanks be sent to the following, who had sent gifts for the inmates during Christmas: Kesteven Blind Society, Mrs

T M Baxter, Miss Chamberlain and pupils of Stamford House School, Dr and Mrs Galletly, Mrs

H A Sneath, Miss Cross, Mr C A Smith, Mrs J H Berry, Cannon Grinter, Messrs Lee and Green, Mrs

J T Holmes, Miss Bell, Mrs O Pearson, Mr E B Binns, Mr C W Bell, and Mr

J Mawby. The Clerk read a letter from an eleven-year-old boy

inmate who wrote that all in the House had a happy Christmas, and wished the Board a bright New Year. He referred to the lovely toys which Santa Claus had brought them, and added that the Matron had said that if they were all good they would have a New Year's party. The letter concluded: "From one of the grateful little boys." The Board was highly

pleased with the letter.

-

Friday 12th January 1923.

A HAPPY TIME FOR POOR LAW

INMATES:

Outside

attractions were scarce during Yuletide, owing to the snow and

gales. On Christmas morning, a comic football match could only be

partially carried out, as several of the players from the

surrounding villages could not put in an appearance owing to the

wretched weather. At the Abbey Church and all the Free churches,

seasonal services were held, retiring collections being taken on

behalf of Bourne Butterfield Hospital. The inmates of Wellhead

House had their usual Christmas fare, and at the mid-day meal, the

staff were assisted by Supt. Duffin, Rev Glyn Morgan (religious

instructor), Mr W Kelby and Miss Bell (members of the Board of

Guardians), Mr C W Bell (clerk), and Mr W E Venters. A Christmas

tree provided by Mr E B Binns, was loaded with toys purchased with

money contributed by the Guardians and friends. The premises had

been tastefully decorated by the Matron (Mrs Hancock) and staff.

- Friday 30th December 1927. |

|

A POPULAR WORKHOUSE

MASTER

The position of workhouse master was an important one and those who filled it were often pillars of the community, unlike the harsh and despised officials depicted in Victorian literature.

The high esteem in which some were held is amply illustrated by Mr Alfred Yates who died at the age of 60 in April 1910. He had been in charge of the Bourne Union for almost thirty years and had previously

held a similar post with the union at Toxteth Park in Liverpool and before

that had served as master of the workhouse in Leeds. He and

his wife Elizabeth were appointed master and matron at a special

meeting of the Board of Guardians on 8th September 1880 when

applications from 18 other couples were considered after

interviews and a check on their testimonials. Their agreed salary

was £75 per year plus food and accommodation. At the same

meeting, three applications were considered for the position of

workhouse nurse and Mrs Harriet Miller of Doncaster was appointed

at a salary of £20 a year plus food and board.

After moving to Bourne, Yates became well known in the

district and took an active part in many social functions. He regularly played cricket for the town and often acted as umpire and he was one of the founders of the Bourne Horticultural Society and later a principal exhibitor and prize winner. Mr Yates was also fond of fishing as a pastime and an active member of the Bourne Angling Association.

But his main interest was in freemasonry and he was a prominent member of the Hereward Lodge in Bourne to which he was strongly attached and had held various offices including Worshipful Master to which high honour he had been twice

elected, in 1896 and again in 1909. For many years he also sang

with the Abbey Church choir and until his health began to fail, he was one of the more regular attenders.

Yates is buried in the town cemetery and when the funeral cortege passed by, the blinds in all of the houses along the route were drawn as a mark of respect and his friends followed the hearse on foot through the streets to the graveside. His wife Elizabeth survived him by 40 years and died at the age of 95 in 1950 when she was interred in the same umarked grave.

Reporting his death, the Stamford Mercury newspaper said: "His passing has come as a great shock to his family and to a large circle of friends. He always endeavoured to treat his inmates with kindness and sympathy whilst he was also regarded by the Board of Guardians as an excellent officer." |

|

WHEN THE WORKHOUSE

MASTER WAS A MRS

The workhouse was usually controlled by a master and matron, invariably a husband and wife team, and in the male-dominated society of the time it was extremely rare to find the job in the hands of a woman alone but that is exactly what occurred at Bourne.

When Alfred Yates died in 1910 (see box above), the posts of master and matron were advertised and eventually filled by Sidney Hancock and his wife Margaret. Mr Hancock had joined the poor law service on leaving the army, serving nine years with the

colours, seven of them in India with the 21st Lancers, and had retired with the rank of sergeant. On moving to Bourne, he soon took a keen interest in the local community, becoming captain of the Bourne Rifle Club and a prominent worker on the committee of the Bourne Horticultural Society and he was also a successful exhibitor at their shows. He was also well liked in the workhouse and in the town.

But his health deteriorated and after several months of illness, he died on Sunday 24th January 1915 at the age of 42. Doctors decided that death was due to an "an internal complaint" and the local newspaper recorded the standing he had achieved in the town during his short time as workhouse master:

"As a public servant he had earned the respect and esteem of those with whom he came into contact, whilst his treatment of the inmates in the house had won their gratitude. No more eloquent tribute of this could be found than the spontaneous expression of the inmates at the Christmas festivities. He frequently arranged concerts during the winter months and the entertainments were very much appreciated. His premature death came as a shock to his many friends in the locality and on all hands there are expressions of deepest sympathy for Mrs Hancock in her bereavement." The funeral was held at the Abbey

Church and afterwards he was buried at Bourne cemetery

where there were a large number of floral tributes

including one from the Board of Guardians. Prior to the funeral, the workhouse chaplain,

the Rev Dr Arthur Madge, conducted another service attended by the inmates of the workhouse.

The Guardians immediately started trying to find a married couple as a successor to the Hancocks

but Mrs Hancock was determined to keep her job and took

the unprecedented step of writing to the Board, thanking

them for their kindness and consideration following her

husband's death and asking them to appoint her as Chief

Officer with a master's clerk to assist.

"In view of my past experience, I feel

confident of being able to manage the house", she wrote.

There was some opposition but a suggestion that a new master and matron be found was rejected and Mrs Hancock was appointed with a salary of £60 a

year (almost £3,000 by today's values), a £5 increase on the usual rate, with £40 a year for an assistant master to be appointed "the latter to be over 40 years of age".

She proved to be extremely efficient in her job, making many

changes to the benefit of the inmates. Many regarded her as a

strict disciplinarian but she was credited with making living in

the workhouse more like a home.

|

To many of the inmates, she had a heart

of gold and she herself was proud of having brought hundreds

of babies into the world during her 26 years there. Mrs

Hancock served as matron until 1936 by which time the

workhouse had been re-designated Bourne Public Assistance

Institution and was also known as Wellhead House. When she

retired, the Board of Guardians presented her with a large

tray to mark her years of service. On leaving, she took a

boarding house in Scarborough before retiring fully to live

in Preston. She died in the late 1950s at the age of 90 and

although she had bought the space to be interred with her

husband in Bourne cemetery, it was not taken up and she is

believed to be buried in Lancashire. |

|

|

|

FROM THE ARCHIVES |

|

BOURNE UNION, October 13th, the Rev Joseph

Dodsworth in the chair: A charge of unkind treatment preferred by

William Smith, an inmate of the workhouse, against the Master, was

fully investigated. The pauper was frequently in the habit of

leaving the house for no other purpose than that of leading a

vagabond life through the country, and shortly after returning in a

very filthy and diseased state; for which, it appeared on taking the

evidence, the Master had made a very proper distinction between him

and the other well-behaved inmates in not allowing him to walk in

the garden. The pauper also stated that he had not been supplied

with a sufficient quantity of lotion for his leg. The medical

officer and the boy employed at the gate were examined, and the

Board having deliberated upon the merits of the enquiry, came to the

following resolution, which was read to the Master and the pauper,

viz., - "That the charge brought by William Smith against the

Workhouse Master is entirely groundless; and that the pauper be

severely reprimanded from the chair for this second attempt to fix

charges of negligence upon the officers of the board without any

cause." - news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 29th

October 1841. After the close of

business at the Guardians' meeting on Thursday the 17th inst., Lord

Willoughby d'Eresby, in the chair, accompanied by the Rev W E

Chapman, W Parker and W D Bell Esq., inspected every apartment of

the establishment and passed a pleasing encomium on the master and

matron for the extreme cleanliness and good order which prevailed

throughout. - news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 25th

August 1843. Several labourers and their

families, in all numbering 27 persons, belonging to the parish, were

on Friday necessitated to become inmates of the union [workhouse]

where they still remain. - news report from the Stamford Mercury,

Friday 16th February 1844. BOURNE UNION:

H B Farnell Esq., Poor Law Inspector, paid his first visit to the

Union on the 26th ult. He threw out many valuable suggestions, some

of which the board will undoubtedly endeavour to carry out,

particularly with reference to the refusal of relief to able-bodied

vagrants. One week's trial has already proved that a good result may

be anticipated. The average number of vagrants during the past

quarter has been about 70 weekly: last week only 33 applied for

relief, four of whom received a night's lodging without food. If the

inhabitants would be unanimous in refusing relief to beggars, or

rather impostors, it would soon be found that not a tramp would

enter the parish to ply his calling.

The Government Inspector of Schools has also attended the workhouse

and examined several classes: both schools went through their

examinations in a very satisfactory manner: the answers to

scriptural questions by both boys and girls was highly gratifying,

and in arithmetic and all other branches they were equally pleasing.

The schoolmaster and schoolmistress also had their abilities tested,

they having to pass through the ordeal of an examination. Mr Farnell

and Mr Bowyer, at the close of the business, inspected the workhouse

and Mr Farnell made the following report: "I have this day inspected

the workhouse and I am happy to be enabled to report it in good

order throughout." - news report from the Stamford Mercury,

Friday 4th May 1849. An inquest was held

on Saturday at the Union House on the body of a pauper named John

Brummitt, 68 years of age, who had died suddenly on the previous

day. The deceased, who belonged to Langtoft, had been about two

years in the house. From the evidence of the master, Mr Holland, and

of an inmate named William Harrison (a cripple from Crowland), it

appeared that the deceased had, up to Friday, enjoyed good health.

Sometime ago, he had an attack of paralysis from which he had quite

recovered and had since been active and in good spirits. A few

minutes before his death, he was sitting on a bench in the aged

men's ward and Harrison observed that his breathing seemed to be

very laboured and gave an alarm. The master was immediately in

attendance and Mr Bellingham, surgeon, was sent for but the poor man

instantly expired. Verdict, natural death.

- news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 22nd August 1851. On Wednesday

last, a tramp named John Welsh, was taken before Major Parker

[chairman of the Bourne magistrates] charged with tearing up his

clothes in the workhouse. He had been admitted the night before and

in the morning was found to have completely destroyed trousers, coat

and waistcoat. He was committed to prison for fourteen days. -

news item from the Grantham Journal, Saturday 19th May 1877. John Glenn, of Bourne, was sentenced to

fourteen days' hard labour for disorderly conduct in the Union

workhouse on 14th inst. - news item from the Grantham Journal,

Saturday 13th January 1883. TREAT FOR

POOR CHILDREN: On Saturday, Mr Frederick Barsby [grocer, of North Street],

gave a treat to the workhouse children in the shape of a packet of

sweets and one of his biscuits for each child. - news item from

the Grantham Journal, Saturday 9th June 1888. |

See also

The workhouse children

Tales from the workhouse

The end of the

workhouse

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|