|

Toft

Tunnel

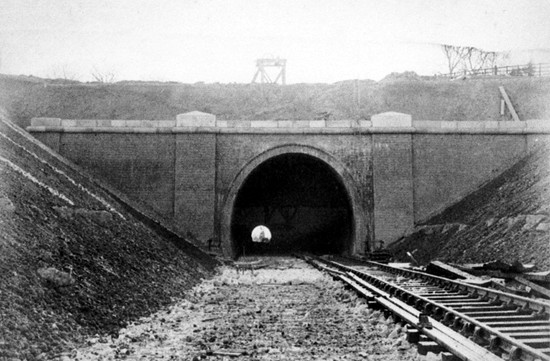

The eastern entrance of the tunnel

One of the biggest civil engineering feats for the railway system in the area during the 19th century was the construction of a tunnel on the outskirts of Toft village, three miles south west of Bourne, as part of the railway link between the Midlands and East Anglia.

The Bourne and Saxby Railway Act was passed on 24th June 1889 for the construction of a double track between the two areas but the section east of Little Bytham was the most difficult part of the proposed route because the terrain rose in a series of ridges and although they were not particularly steep, they combined to create a climb from 35 feet above sea level at the Bourne end to a high point of 439 feet above sea level between South Witham and Wymondham on the

county border with Lincolnshire and Leicestershire.

The escarpment overlooking Bourne presented too sharp an incline to allow engineers lay rails over the top and so it was proposed that a tunnel be driven through it for a distance of 330 yards and wide enough to take two tracks. Survey work started in November 1890 and the actual tunnelling began the following February with an initial workforce of 100 soon expanding to around 400.

Clay from a site near to the tunnel provided the raw materials for one million of the 2½ million bricks needed to line the interior walls and for the construction of the viaduct at nearby Lound and these were made by a manufacturing company set up by

Henry Kingston of Bourne. The town stands on the very edge of a huge belt of Oxford clay that stretches from Dorset through Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire to the Humber estuary, and in the late 1880s, Kingston had exploited this natural resource and opened a brickworks at the foot of Stamford Hill on the edge of the town, a few hundred yards west of the railway station and near a wooden footbridge that was erected later and which eventually became known locally as the Red Steps.

The brickworks were now conveniently situated to the new line and Kingston was given rail access to his premises to supply the bricks needed for the project. The company agreed to build a single siding known as Kingston's Siding provided that the owner paid for the work himself and so the new facility was duly installed. Spoil removed as the tunnel was cut was transported to Spalding at the rate of four trains with 20 wagons each day, carrying between them 400 cubic yards of earth which was used to form an embankment for a new loop line that was being built at the same time. In order to facilitate the conveyance of materials such as bricks from Bourne to the workface, a 2½ mile tramway was laid to serve the tunnel and a whole collection of workshops, a sawmill, mortar mill, smithies and carpenter's shops, grew up around the workings. The tunnel shafts were served by two winding engines while the air below ground was kept tolerably fresh by the use of a Roots patent blower to ventilate the excavations. Water was supplied to the site of operations by a 1¼ mile length of pipe fed by a borehole at Bourne.

|

|

|

Workers taking a break from excavating the

cutting near Toft Tunnel circa 1891 and below the completed tunnel

waiting for the railway lines to be laid. |

|

|

The tunnel took two years to build and by the end of February 1893, the final stage of the project had begun in readiness for the line to open for goods traffic the following June. A freight train from Leicester reached Bourne at 7 a m on Monday 4th June 1893 on its way to the marshalling yards at South Lynn in Norfolk, the first of 30 such trains that day, a precursor of the amount of business that was to be generated in the years to come.

A special excursion train travelled from the Midlands to King's Lynn on 25th June 1893 although passenger traffic did not officially start until May Day the following year, on Tuesday 1st May 1894, when additional facilities had been built to handle them at the Red Hall in Bourne. There was no official opening ceremony although large crowds did turn out to greet the first train.

The Toft tunnel was not a major project in railway history but it was the only one within the Midland and Great Northern Railway's joint system and the line was used extensively during the summer months to transport passengers from the industrial Midlands to the east coast seaside resorts that were becoming increasingly popular for summer holidays and excursions. The service was particularly in demand on public holidays and by August Bank Holiday of 1936, sixteen extra excursion trains were routed along the line and through the tunnel between 1 am and at midday on Saturday 1st August, most of them heading for Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft but some diverting to Skegness, Mablethorpe and Cromer.

|

|

|

Locomotive No 61763 hauling passenger carriages

emerging from Toft tunnel circa 1930. |

|

|

|

|

A safety alcove used

by railwaymen working in the tunnel when a train passed through

(left)

and a view from inside the tunnel looking eastwards (right). |

But it was not to last. The proliferation of the motor car and competition for haulage from road transport soon sounded its death knell. Both passenger and goods services on the line ended on Saturday 28th February 1959 despite opposition from Bourne Urban District Council to save it and work on removing the track between Castle Bytham and Bourne began in the spring of 1962.

The land on both sides of the tunnel was subsequently bought by Bourne

Urban District Council and a section on the eastern side used for rubbish

dumping and when the authority was superseded by South Kesteven District

Council in 1974 it was planned to extend refuse disposal throughout the

site but the proposal was shelved. Later, during the Cold War period of

1979-85 when there was a presumed threat of a nuclear attack, Lincolnshire

County Council investigated the possibility of using the tunnel as a

public shelter equipped with beds, food stores and other survival

equipment but it was deemed not to be feasible and the idea was dropped.

Then in 1993, Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust stepped in to preserve the

tunnel and surrounding area as a nature reserve open to the public. It

consists of the two deep eastern and western cuttings

that include a large portion of gorse, buckthorn and cowslips, a pond and wet

areas of limestone grasses and also acts as a linear wildlife park. In the

summer of 2003, a pyramidal orchid and a common spotted orchid were found on the site and as conditions are perfect for both species, there are hopes that the numbers will increase in future years. The

area can become very wet in winter but an all-weather raised path in the east cutting has been built for access. The mixture of scrub and open areas with rich grassland provides a diverse range of habitats. Whitethroat and willow warbler are regular nesting species, while in winter there are often large numbers of fieldfare and redwing. Twenty-one types of butterfly have also been recorded. The trust continues a programme of annual management, mainly maintaining areas of dense hawthorn and blackthorn trees and also restoring some areas of permanent grassland.

This relic from the heyday of Victorian travel now provides a new delight for those in the 21st century who seek out nature that has colonised the abandoned track which is well worth a visit at any time of the year

although the tunnel itself has now been closed.

|

|

|

|

The tunnel was closed in the autumn of 2006

after engineers ruled that it was unsafe and that visitors would be

in danger from falling masonry. Decades of soot have taken their

toll on the interior brickwork which has started to crumble and fall

in some places. Metal palisade fencing has been erected across each

end, thus isolating the surrounding nature reserve. The future of

the tunnel is now uncertain although there are fears that the new

restrictions may be the start of proceedings to demolish the

structure altogether.

Photos courtesy Jonathan Smith |

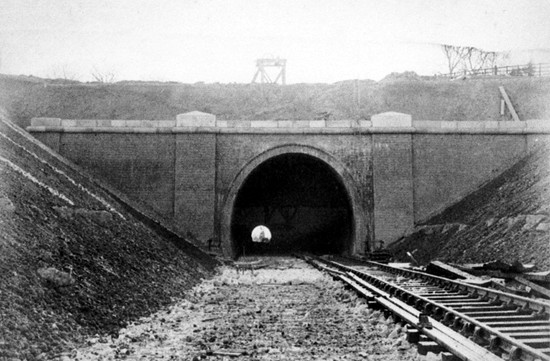

The western entrance of the tunnel

|

WHEN COAL WAS STRUCK

LIGNITE or brown coal, is now being unearthed in the shaft of the

new railway tunnel through Stamford Hill [at Toft] west of Bourne.

This hill is mainly composed of the argillaceous rock known as

Oxford clay which is here excellently adapted for the manufacture of

fine red bricks. The excavation now proceeding reveals the fact that

the lower part of this formation consists of shale. This bed of

shale is composed of hardened vegetable matter, the remains of an

ancient forest, condensed by the overlying rock. The most

superficial inspection betrays the original fibres of the woody

stems that composed it, crossing each other in all directions. We

have further verified this by microscopic examination. The alumina

of the lower strata of clay is strongly impregnated with the oxide

of iron. The shale unearthed possesses the properties of coal for it

will readily burn. Indeed, these "brown coals", as they are called,

were used for fuel in some parts of Germany and Austria. Portions of

the stems of plants peculiar to the carboniferous period, which

generally occur in the shales and sands forming the "roof" of a coal

seam, have been found. Though it would be both unscientific and

ridiculous to hastily deduce from these superficial evidences the

existence of coal in the underlying strata, it is only natural that

the progress of the excavations should be observed with keen

interest alike by local geologists and by commercial men. - news

report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 13th February 1891. |

REVISED OCTOBER 2009

See

also Railways

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|