|

Racing trials on

fenland roads

THE PERILS OF TOFT HILL AND THE

CHALLENGE FOR FRANCIS GIVEEN

The fen roads around Bourne were

perfect for the testing of racing cars and Raymond Mays (1899-1980), motor

racing pioneer and champion of the international circuits, took full

advantage of them and because they were long and flat and with little

traffic about in those days, he could use them frequently without

interruption. His father, Thomas Mays, was a magistrate, and so Raymond's

standing in the community was such that few people would be prepared to

complain if they were inconvenienced by his activities and as a result, he

was frequently found blocking the road to improve standing starts or to

make speed checks over measured distances.

His favourite section for high speeds was the South Fen road between what

is now Cherryholt Road and the turn off into Tongue End which gave a good

two mile run, so enabling the car to open full throttle and reveal any

imperfections. For longer endurance tests, he went further afield, using a

circular route between Bourne and the Great North Road, turning south at

Colsterworth to Stamford and thence back to Bourne which gave him a

sufficiently high mileage to judge performance.

As his main interest at that time was hill climbs, he had the added

advantage of using Toft Hill on the way to Stamford, one of the most

dangerous roads in the area, now a winding

section of the A6121 with a steep incline and sharp double bend which runs from

farmland on the uplands to the west of Bourne through the village and out

into the open countryside, a distance of about one third of a mile. The

hazards of driving this way are acknowledged by those who know the route

and the many warning signs, both on the carriageway itself and on the

grass verges, because a moment of lost concentration could end in

disaster.

|

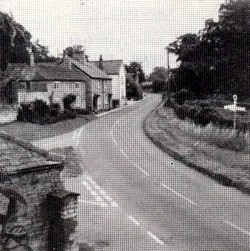

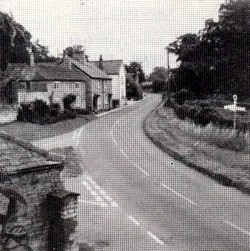

TOFT HILL

One of the most dangerous sections of road in

the Bourne area is Toft Hill on the A6121 three miles south of

Bourne and consisting of a steep incline with a blind double bend.

Even experienced motorists today slow down when reaching this point

from whichever direction they approach because it is impossible to

see ahead and the first bend leaves no room for manoeuvre in the

event of making a wrong decision. |

|

It is therefore surprising to discover that Mays used this

hill for his trials and not all of them were

successful. One of his first models was a Bugatti known as Cordon Bleu which

he eventually sold to a young Oxford undergraduate, Francis Giveen, who

was new to motor racing and needed to be taught how to handle such a fast

car. But he was determined to race and so Raymond invited him to spend the

weekend at Eastgate House in order to polish up on his

driving in readiness for a hill climb race meeting later in the year, the

opening event of the season at Kop Hill, near Tring in Hertfordshire, on

28th March 1925.

Giveen had already owned the Bugatti for two months but had found it

difficult to handle such a fast, light machine and after several runs

through the narrow lanes around Bourne, Raymond decided to pit him against

his favourite slope, Toft Hill, where they duly arrived one morning with

friends and relatives to supervise the course and warn of any approaching

traffic.

Raymond took Giveen as passenger for several fast runs which went off

without mishap and then it was his turn to try himself. “He seemed quite

happy and obedient to my strict instructions to do several runs and work

up his speed gradually”, said Raymond when recalling the event in later

years. “But then he came in for some special racing plugs to give the car

a full throttle effect. Cordon Bleu roared up the narrow lane emitting

that lovely and unique exhaust note, round the acute left hand corner

which was followed by a bend to the right. But as he was leaving the

corner, Giveen skidded and, with his foot hard on the throttle, hit the

right hand bank with a sickening thud, shot across the road broadside, hit

the opposite bank and turned the car completely upside down.”

Dead silence followed and there was no sign of life and those attending

the trials rushed over to the crash scene. They lifted the car on its side

and found Giveen underneath, alive and practically unscathed, saved by a

small Triplex screen that had borne the whole weight of the vehicle while

upside down and had so saved his life, while the car was hardly damaged

except for a few dents.

Raymond spent another day with Giveen trying to give him confidence but

was unhappy at the thought of him driving in competition some weeks’ later.

In the event, he ran off the track while approaching a bend, leaped into

the air, jumped a small sandpit, knocked over some spectators and

disappeared from view but miraculously rejoined the course and finished

the race although he could remember nothing about it afterwards. No more

cars were allowed to run that day and ironically, as a result of the

incident, hill climbs on public roads in England were stopped for ever.

Fortunately, no one was killed and all of those injured recovered but

ironically, it was Giveen’s crash that sealed the fate of these classic

events that had been pioneered by Raymond‘s father, Thomas Mays.

In the spring of 1930, Raymond

Mays received a letter from Francis Giveen saying

that he was experiencing problems and asking for a meeting to discuss

them. This was revealed by Mays in his book, At Speed, which was published

in 1952 but hastily withdrawn from sale for reasons unconnected

with this incident.

The two men subsequently met and dined at the Grosvenor Hotel, London,

where they both presumably stayed the night. Mays was alarmed at Giveen's

state of agitation and the following morning, on leaving his room, Mays

met one of the porters who said: "Have you seen your friend, Mr Giveen,

sir? He was walking up and down the corridor outside your room last night

flourishing a revolver."

Two days later, Giveen's body was found on the towpath alongside the River

Thames at Medley Weir, Port Meadow, near Oxford. He had apparently shot

himself after taking a taxicab to the river carrying a double-barrelled

sporting gun. Another man who happened to be walking along the towpath at the time,

Alfred Bradbury, a driver's assistant, of Caversham, near Reading, was

taken to hospital with shotgun wounds over his body.

On Wednesday 21st May 1930, an inquest was held at Oxford on Francis Waldron Giveen, aged 23, when evidence was given by his father, Henry

Hartley Giveen, a distinguished lawyer and King's Counsel, who revealed that his

son had spent three months in a mental home earlier in the year. "While he

had been climbing in Cumberland, he had suddenly decided to go to Paris",

he said. "Then I had information from one of the government officers that

he had been interned in what corresponds to an English lunatic asylum. I

sent someone out to look after him and he was taken away from that place

and put in a sort of mental home in France. He was medically supervised

and came back to England on April 17th on the recommendation of the doctor."

Michael O'Sullivan, surgeon at the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford, said in evidence

that the cause of death was shock and haemorrhage following a gunshot

wound in the face. A verdict of suicide during temporary insanity was

returned. Mr Giveen expressed his sorrow that Alfred Bradbury had been

wounded and said that he would be fully compensated.

|

ROAD TESTING IN THE FENS |

|

|

|

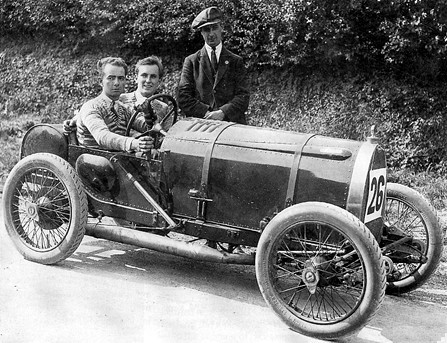

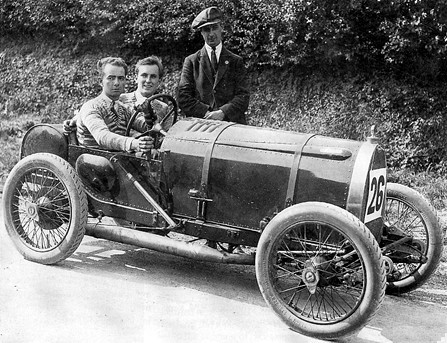

Practising a standing start with the Brescia

Bugatti on the South Fen Road near Bourne in 1922 with Raymond Mays

at the wheel, Amherst Villiers with the stop watch and mechanic

Harold Ayliffe, seated. The photograph below was taken in 1934 and

shows one of the first ERA cars ready for a road test on the

circular route from Bourne to Colsterworth, south to Stamford and

back to Bourne. |

|

|

NOTE: The top photograph shows the 1.5

litre Brescia Bugatti known as Cordon Bleu in 1924 with

Raymond Mays at the wheel, Amherst Villiers in the passenger seat and

mechanic Harold Ayliffe.

Return to

Raymond Mays

Toft village

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|