|

Days of the soup kitchens

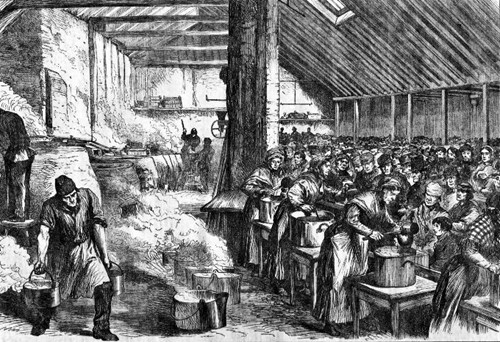

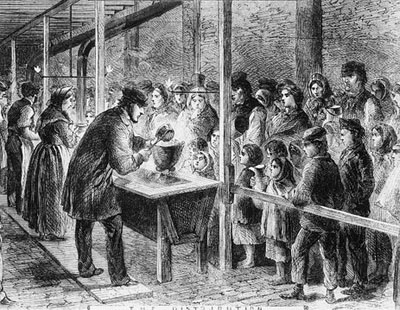

Soup is a cheap and efficient method of distributing nutrition to people in need because it can be prepared comparatively cheaply in large quantities and therefore became popular as a means of feeding huge numbers of people in times of deprivation, particularly during the 19th century. Soup kitchens were established whenever conditions were hard or the weather inclement for long periods, providing a place where food was offered to the poor free of charge or at a reasonably low price. They were usually funded by wealthy citizens or religious and charitable organisations as an act of philanthropy and in Bourne, they were set up at suitable locations such as the Town Hall, staffed by volunteers from church groups and elsewhere. The notorious American gangster Al Capone financed a soup kitchen in the United States during the Great Depression, possibly to improve his image, while in London, the Islington Soup Kitchen founded in 1863, served during the winter of 1903-04 a total of 7,031 quarts followed the next winter by 7,234. Soup kitchens can still be found in many countries in poor neighbourhoods as a service to the deprived members of society. Until 100 years ago, bread was the staple diet for most

ordinary or labouring families and a survey of 1860

discovered that many adults consumed around 12 lbs. every week. It was

often made more palatable by being covered with dripping or, very

occasionally, a little butter. Small quantities of bacon, salt pork, beef,

cheese and porridge also formed part of many poorer people’s weekly diets

although such nourishing foodstuffs were more frequently reserved for the

man of the house who needed to keep up his strength to maintain the

family’s income. Put an ox’s head, well washed, into 13 gallons of water, add a peck and a half of pared potatoes, half a quartern of onions, a few carrots and a handful of pot herbs, thicken it with two quarts of oatmeal (or barley meal) and add pepper and salt to your taste. Set it to stew with a gentle fire early in the afternoon, allowing as little evaporation as may be, and not skimming off the fat, but leaving the whole to stew gently over the fire, which should be renewed and made up at night. Make a small fire under the boiler at seven o’clock in the morning, and keep adding as much water as will make up the loss by evaporation, keeping it gently stewing until noon, when it will be ready to serve for dinner. The whole may be divided into 52 messes, each containing (by a previous division of meat and fat), a piece of meat and fat and a quart of savoury nourishing soup. The expenses of the meals are: ox’s head 2 shillings and sixpence; potatoes, onions etc 1 shilling and 1 penny; 2 quarters of oatmeal 11 pence; cost exclusive of fire and cooking: 4 shillings and 6 pence. At that time, the workhouse in Bourne was situated in North Street at the corner of what is now Burghley Street, then called Workhouse Road, and no doubt every drop was eaten with relish by the inmates because the old adage that beggars could not be choosers was never more true than for those who were unfortunate enough to have ended up living there. SOUP KITCHENS DURING THE 19TH CENTURY FOR THE PAST MONTH, about 220 gallons per week of most excellent soup, costing about 3d. per quart, have been distributed to all the necessitous poor who have applied for it and no doubt good service has been rendered to many persons who have suffered from the late inclement weather and want of employment. The fund raised for this object amounted to £34 15s. 7d. There have been eleven distributions of about 80 gallons each time and the last distribution for the season is intended to take place today (Friday). Each distribution, on an average, was purchased by 324 families, comprising 500 adults and 700 children. The cost of each distribution was about £4 and one third of that sum was received from the applicants at the rate of 1d. per quart. Thanks are due to the committee for the efficient manner in which they have discharged the duties devolving upon them. - news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 1st February 1861. A MEETING WAS HELD at the Town Hall on the 7th inst. to consider the desirability of establishing a soup kitchen during the inclement weather. The curate, the Rev J P Sharp, took the chair and a committee was formed, subscription lists opened and on three occasions, on Saturday, Monday and Wednesday, about 60 gallons of soup of excellent quality have been served out at a halfpenny a pint to a large number of applicants. About a dozen subscriptions have been opened: one at each of the banks and others with various tradesmen, where it is hoped that those who desire to support the soup kitchen will leave their subscriptions and thus avoid the necessity for a house to house collection, the committee having determined to adopt the former course. - news item from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 15th January 1864. Today, soup kitchens survive to help the homeless and destitute in many parts of the world while for the rest of us, soup is considered to be a small luxury rather than the necessity of past times, bought in tins at the supermarket or as a starter when dining out. Next time you tuck in, remember that it was once a lifeline for the poor.

REVISED AUGUST 2012

Go to: Main Index Villages Index

|