The mediaeval monk Robert Manning is well known for his close connections with Bourne but a modern writer with the same surname although less well known also has strong links with the town.

He was the novelist and poet Frederic Manning who was born at Sydney in Australia, on 22nd July 1882, the fourth son of Sir William Manning, financier and politician and four times Lord Mayor of Sydney, and his wife Honora, both of Irish descent. He was a lifelong asthmatic and apart from six months at Sydney Grammar School, was educated privately and at the age of fifteen he came to England with his tutor the Rev Arthur Galton who was a friend of Matthew Arnold and Lionel Johnson and had gone to Australia as private secretary to the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Robert Duff. On the outbreak of the First World War, Manning tried to obtain an army commission but after failing an officers' course, he enlisted in 1915 as a private in the King's Shropshire Light Infantry and served in France and fought at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He was promoted second lieutenant on 30th May 1917 in the Royal Irish Regiment of Foot but resigned his commission because of poor health and disagreements with his fellow officers.

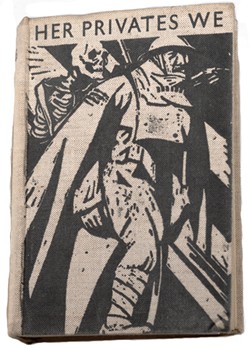

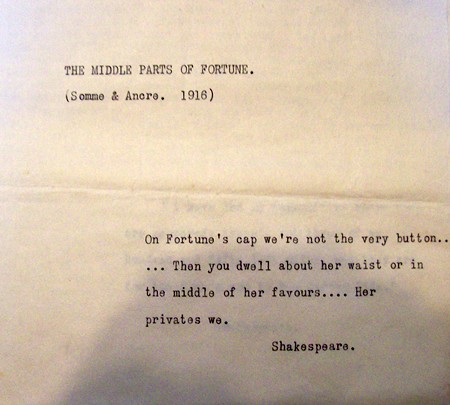

That year he published a third volume of poetry Eidola which included some war poems and after his discharge, he lived mostly in Italy. Several more books followed including a biography, but constant ill health was taking its toll and his friend Sir William Rothenstein described him as having "the worn look, as of carved ivory . . . and the sensitive intelligence one finds in men of fastidious habits". His only hobbies were horse racing and book collecting but friends, including Lawrence and T S Eliot, found his conversation "extraordinary for its learning and charm". Manning's writings were already highly respected by Lawrence who regarded him as one of the three writers he most cared for, the others being E M Forster and the Armenian poet Ernest Altounyan. Her Privates We, he said, was "a book in a thousand, a masterpiece". When Lawrence obtained a copy he at once recognised the author as Manning from his earlier work Scenes and Portraits and he immediately went to the nearest telephone and called the publisher Peter Davies, godson of J M Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, at his office in London to congratulate him on "this masterpiece". Davies eventually introduced them and their friendship began, mostly by letter, but there were also several meetings until Manning's death five years later which devastated Lawrence. The now famous telephone conversation between Lawrence and Davies about the book was subsequently used in the advertising material for Her Privates We.

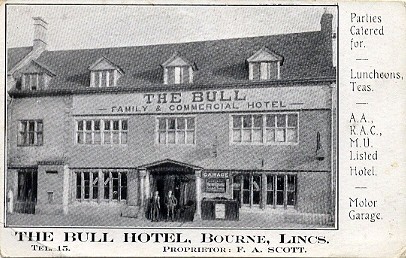

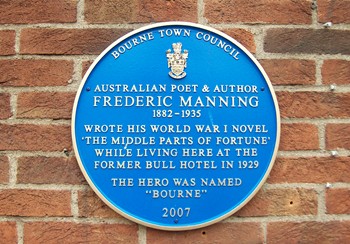

The book is in fact dedicated to Davies who he said "made me write it". It was generally acclaimed by the critics of the time including Arnold Bennett and one newspaper said: "Whoever he is, this Private 19022, about whose identity so many are speculating, he can write. The whole atmosphere, rhythm and whiff of the front comes at you from every page." But the novel faded away and Manning remained relatively unknown in both England and Australia until 1977 when Her Privates We was re-published, again to much critical acclaim, and this appraisal as the classic novel of World War One remains to this day because the book is about soldiers and above all about friends. There is no doubt that Manning had a deep affection for Bourne and returned to the town for long periods and most probably wrote his famous novel here. On these frequent visits, he lived at the Bull Hotel in the Market Place [now the Burghley Arms] but he was by nature very shy and his ill-health made him even more retiring and so only a few people in the town ever knew that he was here. He went back to Australia in December 1932 and was welcomed in Sydney as one of the finest literary stylists of the day, returning to England the following year to stay at the Bull Hotel. His physical condition, however, had deteriorated and he was in need of constant treatment for chronic respiratory problems and Dr John (Alistair) Galletly, who had become a friend as well as medical adviser, later recalled attending him in his bedroom at the Bull where, with oxygen cylinders within reach, he would be inscribing yet another blank page with his meticulous but diminutive handwriting. Eventually, Manning became so unwell that Dr Galletly suggested a prolonged spell of sunshine and so he returned to Australia early in 1934, a visit which was to be his last. During his time at the Bull, he had also become firm friends with the landlord and his wife, Fred and Eliza Scott, and their daughter Gladys and in later years she remembered seeing Lawrence arrive one afternoon, a slight figure in his Royal Air Force uniform, on a motor cycle on his way south, asking after Manning and, after hearing that he was in Australia, resumed his journey.

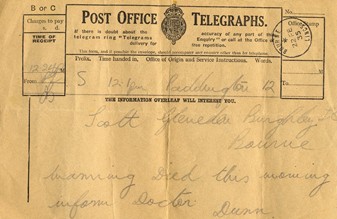

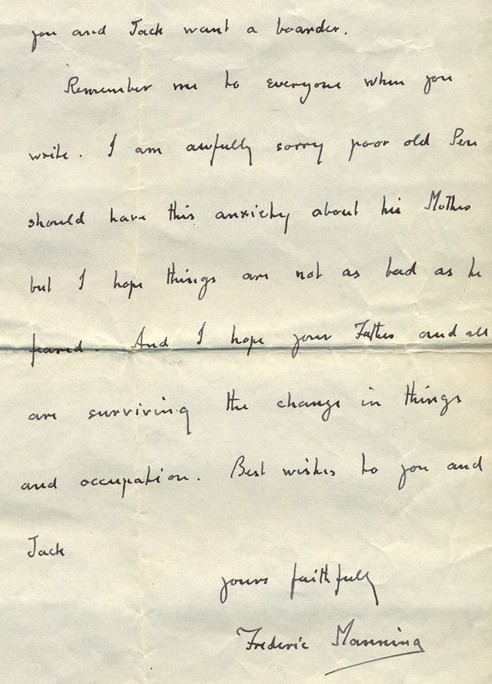

It was during this period that the Scotts gave up the tenancy after 12 years while Gladys, who had married Jack Gelsthorpe, had moved to a house in Burghley Street. Manning, however, had become such a part of the family that he wrote an affectionate letter from Sydney to Gladys on 25th March 1934 saying that as they had all left the Bull, he had less inclination to return to Bourne but still wanted to know whether the inn had changed much. "You might let me know what the Bull is like now in case I should want to go down later", he wrote. "You know the sort of thing, what the people are like and whether I could get the same rooms?" Then as an afterthought he added: "I don't suppose you and Jack want a boarder." The couple took him at his word and agreed to have him and when he arrived in May that year, he was given the front room as a bed sitter. In the ensuing months, Dr Galletly became increasingly concerned about his state of health and as his condition worsened, persuaded him to move to a nursing home at Hampstead in London and actually took him there in his own motor car. Manning died there on 22nd February 1935 at the age of 52 and he was buried in Kensal Green cemetery beside his lifelong friend and literary hostess Mrs Alfred Fowler.

Lawrence, who had then been serving with the Royal Air Force at Bridlington in Yorkshire, had intended to visit him on his motor cycle around this time but on February 28th, he wrote to Peter Davies: On Tuesday, I took my discharge from the R A F and started southward by road, meaning to call at Bourne and see Manning: but today I turned eastward instead, hearing that he was dead. A man who can produce one decent book is a fortunate man, surely? Strange to think how Manning, sick, poor, fastidious, worked like a slave for year after year . . . on stringing words together to shape his ideas and reasonings. That's what being a born writer means, I suppose. And today it is all over and nobody ever heard of him. If he had been famous in his day he would have liked it, I think; liked it deprecatingly. As for fame-after-death, it's a thing to spit at; the only minds worth winning are the warm ones about us. If we miss those we are failures. I suppose his being not really English, and so generally ill, barred him from his fellows. How I wish, for my own sake, that he hadn't slipped away in this fashion; but how like him. He was too shy to let anyone tell him how good he was. Sadly, Lawrence himself was to die in a motor cycle accident near his home in Dorset just over two months later on 13th May 1935.

See also The Burghley Arms NOTE:

Picture of Frederic Manning by Sir William Rothenstein, sanguine and

Go to: Main Index Villages Index |

|||||||||||||||||||