|

The Mallard steam

record

SUNDAY 3rd JULY 1938

One of the most important days in

the history of the railway steam age was in 1938 when the Mallard

locomotive set up a new world record by travelling at more than two miles a

minute, a speed that has remained unbroken ever since.

This tremendous feat was achieved on a stretch of track near the railway station at Little

Bytham on the B1176 four miles south west of Bourne. The station closed in 1969 but the village maintains its reputation and is a popular haunt of railway enthusiasts, nestling around a grand Victorian viaduct that carries the main east coast line over the road between London and Scotland.

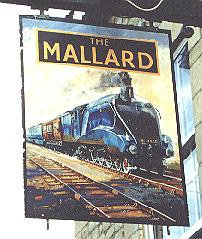

Even the local public house, a 16th century hostelry once known as the Green Man, changed its name in

1975 to The Mallard because of the growing interest in railways and the steam engine record and although it closed in 2002 and is now a private residence, it has been called Mallard House as a reminder of the famous event. The stone house stands in the shadow of the viaduct that is still in use but inter-city express trains rather than steam engines now flash past at regular intervals.

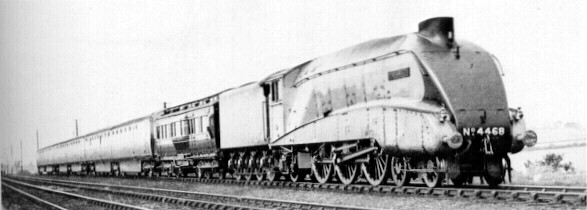

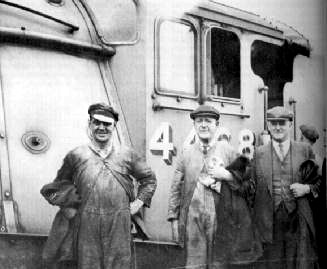

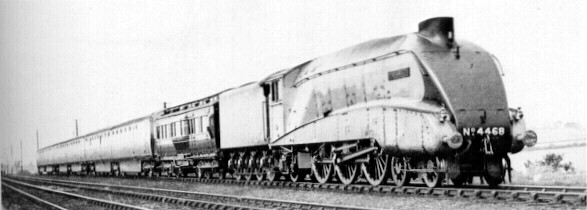

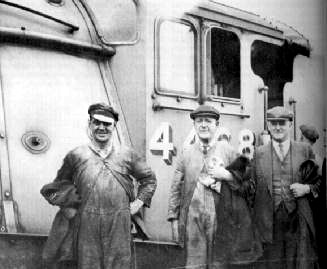

It was on this stretch of track between Grantham in Lincolnshire and Peterborough that the record was broken. On Sunday 3rd July 1938, the London and North Eastern Railway 4-6-2 engine No 4468 Mallard, a streamlined Gresley A4 Pacific, hauling seven coaches weighing 240 tons, achieved the highest speed ever ratified for a steam locomotive of 126 mph over a distance of 440 yards. On the footplate were two Doncaster men, Driver Joseph Duddington at the controls and Fireman Thomas Bray feeding the boiler with coal.

|

|

|

|

The former inn sign

from the Mallard public house at Little Bytham, closed in 2002,

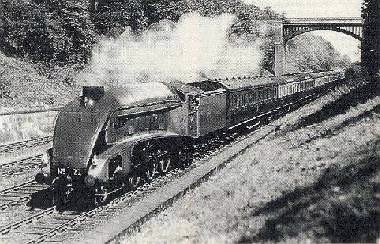

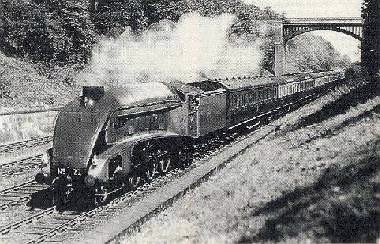

and the Mallard under steam on the main east coast line |

The coaches included a dynamometer car packed with instruments in which engineers were able to follow the exact speed

and to notice any defects in the track and with them was the engine's designer, Sir Nigel Gresley (1876-1941). The Mallard may have been a special train because it carried only engineers and staff but in reality it was no different to the others

that sped daily through Little Bytham station.

The record at that time was held by the Coronation Scot owned by the London Midland and Scottish Railway which, on its inaugural run the previous year, on 29th June 1937, reached a speed of 114 mph. Prior to that, it was another LNER train which held the record, the Silver Jubilee, a familiar sight on this line, and which, when pulled by the Silver Fox locomotive, reached 113 mph on 27th August 1936.

The Mallard had been built at the LNER workshops in Doncaster in 1938 as part of the railway company's programme of attracting more rail customers by offering both speed and comfort but this

had to be demonstrated to the public and a record breaking run was therefore important to their marketing policy. On Sunday 3rd July that year,

the Mallard left Doncaster at 5 am and steamed south and after a short stop late in the afternoon, the train was started a little north of Grantham

and began travelling south towards Peterborough.

No prior announcement was made that a record attempt was imminent, either to the public or to railway staff, although signalmen along the track were told that the train might pass through a little before schedule at high speed. Many workers therefore assumed that this was to be a special run with the railway company attempting to regain the blue riband of the permanent way and were on high alert when the moment came.

The stretch of track between Grantham and Peterborough was chosen for the record attempt because high speeds had been attained there before. From Stoke tunnel, south of Great Ponton station, there is a steady falling gradient and the line slopes all the way to Little Bytham and after passing through the tunnel, the train is able to gather speed which reaches its peak near Little Bytham, so making the next stretch to Essendine the fastest between London and Scotland.

The Mallard arrived at Grantham station and passed through at a modest 24 mph. In the next two miles, it accelerated to

59¾ mph, then 69 mph with Fireman Bray shovelling furiously to keep the fire burning at its maximum to supply all the steam needed as the engine thundered southwards. The train swept past the

mile posts at the side of

the track at an ever increasing pace, recording speeds of 87½ mph, 96½, 104, 107,

111½, 116, 119 mph and then, at the ensuing half-miles, 120¾ mph, 122½, 123,

124¼ and finally 126 mph, by which time the 6ft. 8in. driving wheels were doing more than 500 revolutions a minute.

The train was clocked passing Little Bytham station at 4.36 pm and reaching Essendine, a little under three miles away, at 4.37

pm. It had maintained a speed of over 120 mph for more than five miles and had clocked 126 mph over a distance of 440 yards and so the record was secure. Signalman Walter Humphreys, who was on duty at the Little Bytham signal box, said next day: "We have a special sequence on the

inter-signal box to herald the approach of a flier, four beats on the electric bell, a pause and then four more beats. Moreover, when

the Mallard came through, we cleared twice the length of line of other rolling stock that we would have done for any other ordinary express. These trains normally pass by without any apparent effort at around 90 mph but

as the Mallard came in sight, it was obviously all out with smoke belching from its funnel and going like the devil. A record breaker if ever I saw one."

The Mallard had steamed into railway history by travelling faster than the current holder, the Coronation Scot, and all other steam locomotives in the world whose high speed performances are on record, and it has never been exceeded since. But it was not without cost because the engine was damaged by the severe exertions to which it had been subjected. The big end at the front of the three-cylinder engine failed during the run and the locomotive was forced to pull into the railway engineering workshops at Peterborough for repairs. Nevertheless, the record was in the bag and remains so to this day. The newsreel and press cameras were waiting for the Mallard at King's Cross but she never arrived and therefore no film exists and the only pictures of the great day are amateur photographs taken on box Brownie cameras by the train crew and railway staff.

|

|

Driver Joseph

Duddington (lef) and his fireman Thomas Bray, pictured with the

Mallard after their record breaking run on Sunday 3rd July 1938.

Also in the picture is railway Inspector Sam Jenkins who travelled on the

train

from Doncaster. The record attempt was supposed to have been a

secret but on the day, there was an awareness among railway staff

along the line that something special was about to happen and all

were on a high state of readiness. |

When all the fuss of the record-breaking run was over,

the Mallard went back to work as part of the LNER fleet of locomotives on day to day operations. Then came the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and all the glory faded away and the locomotive was reduced to hauling goods trains around the country until 1945. After that, it was back to pulling trains on the east coast main line between London and Scotland on a daily basis although only for a short while. The LNER was swallowed up in 1948 by the formation of the nationalised British Railways [known as British Rail from 1965], dedicated to a policy of diesel and electric trains which heralded the end of the days of steam.

But a champion like the Mallard was not to be forgotten so easily and it was allowed to retire gracefully after clocking 1,426,000 miles during its lifetime before finally being withdrawn from service in 1963. In 1975, it was moved from London to the newly formed National Railway Museum at York where it can be seen today, one of the main exhibits among a unique collection of relics from our railway past, resplendent in its original blue livery and a reminder of those exciting days of steam.

See also Little

Bytham

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|