|

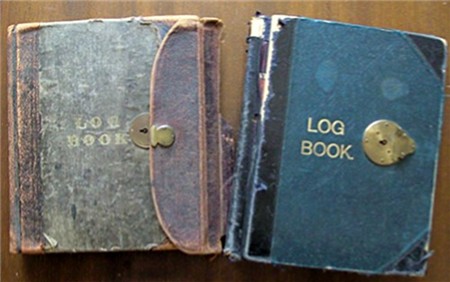

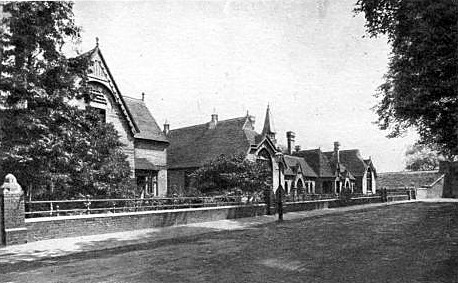

Log books record early school history

Two log books which were kept by

the headmasters of our local primary and secondary schools still exist,

the first dating from July 1877 when the school opened until December 1904 and the second from

January 1905 until June 1989. "I opened the Star Lane Board School this morning. The staff at starting consists of myself and three monitors for the boys' department. These monitors are desirous of becoming pupil teachers. Their names are Arthur Smith, Harry Smith and Frederick Warren. We admitted 36 boys today who were distributed as follows: Standard III - 6; Standard II - 6; Standard I - 24. Of these 24, as many as ten, although over seven years of age did not know their letters and nine could not tell that 2 and 1 make three." Within a month, the school roll had reached 96 and as the school closed for the summer holidays on August 17th, the log book recorded: "Broke up at the close of the morning's work for a month's holiday. The work hitherto has been fairly satisfactory. Order not very good, boys being restless and talkative but no disobedience or wilful disorder. Have worked on the mark system. Gave to Story and to Franks books as reward for obtaining highest number of marks."

From these early beginnings stemmed the primary and

secondary education system we have in Bourne today. The log books cover a

total of 112 years and record

the daily life of the school, the trials and tribulations of teaching and

of truancy, of success and of failure, the effects of war and of the

transition through the various educational changes during two centuries and the dedicated staff who

supervised them. We cannot be certain who wrote all of the entries because the handwriting differs but the majority must have been the work of either the headmaster of the boys' school or the headmistress of the girls' school, or their deputies. However, following the appointment of Joseph J Davies as headmaster of the boys' school on 7th May 1887, it is an easy task to identify his distinctive copperplate handwriting and the erudite entries which chronicled his time in office for the next 33 years. His entry for that first day on 9th May 1887 reports: "I commenced duties in this school this morning. J L Bell, clerk, called this morning and showed me a communication from the Department about irregular attendance. I have commenced inquiries into the reasons of absence of irregular boys." Mr Davies was to discover in the years to come that absenteeism was one of the main problems at the school and for a variety of reasons. In one January week of 1878, bad, stormy weather had caused fluctuating attendance with a "very low" figure on the Friday. A year later, "very deep snow" resulted in only 55 girls turning up out of a total of 120 and on 11th February 1900 "the terrible snowstorm has pulled the attendance down". On a July day in 1901, heavy rain flooded the streets, the school closed in the afternoon and the children were taken home in vans. The very wet weather which caused serious flooding in Bourne South Fen at the end of 1910 prevented "the fen boys from attending" on December 9th. There was a recurrence of these conditions in 1911 which led to further serious flooding of the fens and in November 1912, there are numerous daily entries of "a pouring wet morning", "pouring wet today" and "weather still inclement". Further bad weather in 1920 brought problems and the log book recorded on March 15th: "Most inclement afternoon after continuous snowstorm in the morning. Only 101 present out of 204; most of the boys were very wet, I do not consider it safe to keep them a full session. I therefore, after consultation with girls' and infants' mistresses, have dismissed them at 3 pm without marking registers." Illness and epidemics are also well documented in the records because outbreaks of various infections occurred frequently while coughs and colds were a constant problem. On 27th February 1891, 60 children were absent with mumps and in 1897, the school was compelled to close for a fortnight because of measles. Whooping cough also brought periodic attendance problems, as did many diseases which are now rare, and on 23rd June 1891, the log book recorded: "During the past three weeks, influenza has been very prevalent in Bourne. The board therefore decided to close the school (under the doctor's advice) for a further period of 14 days, as a preventive measure." On 13th June 1892, the log book records an attendance of 180 pupils but "in the afternoon several children were sent home through illness" and on June 17th, the entry reads: "More were absent on Tuesday morning. I made close inquiries and found that the children were suffering from measles. On Wednesday there were 150 present and on Friday 135. Acting upon the advice of the Medical Officer, I have sent home all children in families affected with the complaint." Attendance continued to decline and on June 23rd came the entry: "Attendance so wretched that I dismissed children in the afternoon" and on June 27th: "School closed by order of the Medical Officer of Health for three weeks. At the expiration of this period, an order was received to close the school for two weeks, making five weeks in all." In March 1893, even smallpox is mentioned in the log book, accounting for the absence of certain children, especially those from the Bourne Union, or workhouse. This entry is not surprising, as an outbreak of infectious disease at that time was strongly suspected by the Board of Guardians to be one of smallpox but the Medical Officer of Health did not confirm this and a heated exchange of letters between the workhouse authorities and the Local Government Board failed to establish beyond any doubt whether the disease had or had not been smallpox. Another outbreak was suspected in 1928, although not confirmed, because the log book entry reads: "I have heard unofficially that there are 2 or 3 cases of smallpox in the workhouse. The children from the workhouse are absent from school this afternoon." Diphtheria was also among the most serious illnesses to affect schools at that time because it was so infections and the results could be deadly. The log book records on 12th June 1933: "School closed for a week so that the buildings may be thoroughly disinfected on account of an outbreak of diphtheria in the district." Another illness that is unheard of today was the subject of a log book entry on 6th May 1940: "Children resident in Gladstone Street are excluded by order of the local medical office owing to an outbreak of scarlet fever in the street." Apart from bad weather and sickness, the log books also give other reasons apart why absenteeism was rife. Bourne was in the middle of a rural area where farming was the main industry and at busy times of the year such as the corn harvest and potato picking, every member of the family was needed in the mustering of all possible labour. On 15th March 1879, the log book recorded "attendance lessening, Boys going out to work in the fields" and on July 7th, the entry revealed exactly how widespread the problem was: "100 boys absent today." Then on 13th October 1898, the log book noted: "I have made a special duplicate list of this week's absentee list for Mr Farr (school board) together with a copy of last week's absentee report. In almost every case, the excuse alleged is 'potato picking' or 'at work'. Today the attendance is 120, one of the worst I have known since I came here." The headmaster also had problems with his staff because on 28th July 1879 he wrote: "Bad order today. Harry Smith is pretty nearly useless to keep order. He seems at times to altogether lack energy and sits dreaming before his class" and on August 12th he reported: "Harry Smith and Frederick Warren absent from lessons without leave." The pupil teachers were again in trouble on 28th February 1881 when the log book recorded: "I find that lately there has been a systematic petty persecution on the part of the pupil teachers against the woman who sweeps the school. I have remonstrated with them and pointed out how mean such conduct is but without any effect. On Friday night, taking advantage of my being engaged (elsewhere), they clambered to the school roof and amused themselves and a group of children by throwing stones down at Mrs Walker. I told them then and again this morning that I should require some explanation of this misconduct but it seems they have nothing to say - no apology to offer. I shall therefore show this entry to the School Board at the meeting tomorrow as that seems the only way of convincing the pupil teachers that such conduct is wrong." The matter appears to have been resolved later that day because the log book entry said: "In reference to the above entry, the pupil teachers deny that they threw stones at Mrs Walker or that their visit to the school roof had any connection with her whatsoever, Arthur Smith has the candour to admit that it was indiscreet to go there. That the stones thrown went near Mrs Walker was an accident. I am glad that this incident should end with this explanation." The recruitment and retention of staff were a constant problem for the school, especially with the pupil teachers and in 1893, the log book recorded a tragedy in respect of one of them. On July 24th, Ernest Skinn was absent through illness which continued for the next few days. Then on August 11th, the entry said that although still weak, he had "attended for two days this week" but the school then broke up for the harvest holiday. Lessons resumed on September 25th when the entry read: "Ernest is suffering from a dangerous attack of rheumatic fever. I have notified this to the board." Then on October 1st, the headmaster wrote: "I deeply regret to record that Ernest Skinn died yesterday morning. He was a very promising youth who at all times was diligent in the fulfilment of his duties. Bright, capable and energetic, he possessed a natural gift for teaching and I had looked forward with hope to see him occupy a high and honourable position in the profession. Both by the scholars and his fellow teachers, he was held in high esteem and we all grieve that we shall see him amongst us no more. I feel his loss as a personal sorrow." Two weeks later, the board appointed Mr Skinn's wife, Helen, as a temporary monitor to assist in the junior school. By 1910, the staff had risen to ten, including two ladies although there was still some acrimony among the male members having to work alongside women and this included the headmaster's wife who was occasionally called upon to help as a teaching assistant when staff were off sick or on holiday. On 9th November 1908, the headmaster reported that he had been absent for several days through illness and the log book entry continued: "During my illness, I requested Mrs Davies to take charge of and supervise the junior section as Miss Boyers, the new assistant mistress, only commenced during this week. On Tuesday, Mr Watson resented publicly Mrs Davies' presence in the school in a most objectionable and insulting manner and laid a complaint before the correspondent (clerk to the board) Mr Bell. As the offensive words had been spoken to Mrs Davies in the presence of the boys, on the matter coming to my knowledge, I censured him. A special meeting of the managers was held on Saturday when he was censured and directed to apologise to Mrs Davies for whose long and valuable service in their schools they expressed their appreciation. Mr Watson thereupon apologised." Miss Boyers had only just joined the staff as assistant mistress of the junior section but her stay at the school was to be a brief one. The log book recorded on 29th January 1909 that "she has been absent this week through illness. The doctor informs me that she is very weak and will need quite three weeks' rest." On February 22nd February, it was revealed that Miss Boyers was "suffering from St Vitus's Dance and will be absent for at least a month". Then on March 1st, the headmaster reported: "Miss Boyers' illness is so serious that she has sent in her resignation." Bullying was also an occasional problem and the log book entry for 26th May 1881 records a playground altercation: "Mrs Grummitt brought her son Bertie to me this afternoon to show a black eye made by Albert Reeves, monitor. It appears that in the playground, Reeves accidentally knocked Grummitt down. Grummitt then called Reeves names, who, in return, boxed Grummitt's ears and so cuffed him as to make him a black eye. I have frequently warned the teachers against striking boys. This case had nothing to do with school discipline, as Grummitt is not in Reeves's class."

But absenteeism appeared to be the major worry. In mid-October 1879, when the harvest was significantly late that year,

attendance was affected because "girls were out gleaning" and six years

later, almost to the day, the headmistress reported: "Attendance irregular

- some of the girls are absent getting the potatoes up." In July 1901, an

entry read: "Attendance not so good this week, so many of the girls are

away half-days taking dinner and tea to the hay fields."

The headmaster was also aware that pupils needed some form

of diversion from their lessons because on 17th January 1879, he wrote:

"Good attendance this week. Bought a dozen copies of Boys' Own Paper

for boys to read in class. This is a new The headmaster continued to exercise strict discipline in extreme cases and on 14th January 1880, he records the first case of expulsion since the school began: "I dismissed the boy Edward Buckberry from the school today for bad conduct. He came to school in the afternoon nearly half an hour late and while 'standing out' at a line, employed himself with shooting pellets of paper with a piece of elastic at the faces of some little boys. I warned him that I should cane him if I found him repeating the offence. A little while after, I found him doing the same again. I called him out and he refused to hold out his hand so I punished him and sent him home. I sent a note to his mother telling her of the occurrence and asking her to come to the school and see me. She has not done so. I shall therefore strike the boy's name off the register and not re-admit him till he is prepared to take the punishment which I think is justly due to a boy who flicks little boys' faces with elastic." Drastic measures were again called for on 1st October 1885: "Have had a great deal of trouble this week with the boy Thomas Phillips. He has truanted lately and yesterday ran away from school. His mother says he is quite unmanageable at home. I gave him a sharp thrashing today." Caning was frequently doled out by teaching staff although the headmaster did try to restrict this form of punishment and on 1st February 1901 he recorded: "I have given orders to the assistants to limit punishment to one stroke of the hand. I took note, without previous notice, of the boys who have been punished during this afternoon. Mr Harrison had given 26 boys the cane and Mr Butler 15. In each room, some of the boys appear to have had more than one stroke, hence the above order to which Mr Harrison strongly demurred but I replied by repeating it, finally, and decisively. Mr Butler agreed to my order, not at the first." Two weeks later, the issue surfaced again and the headmaster reported on February 11th: "I found this morning that Mr Butler had given a boy, Tom Hill, two or more strokes. I pointed out to Mr Butler, the order and expressed my opinion plainly. In the afternoon, I deemed it advisable to make my order clear to Mr Harrison who again demurred. I stated that I requested from both explicit assurance on this matter of obedience to my reasonable demand. Otherwise, it would be my duty to report the matter, as by Art 32 (Institute of Inspectors) I must report every case of corporal punishment." The headmaster's instruction was eventually accepted and on February 15th, the log book recorded that "both Mr Harrison and Mr Butler have expressed their agreement to my request". Then on April 4th, he wrote: "Mr Harrison and Mr Butler are heartily co-operating with me on reducing corporal punishment to a minimum with excellent results."

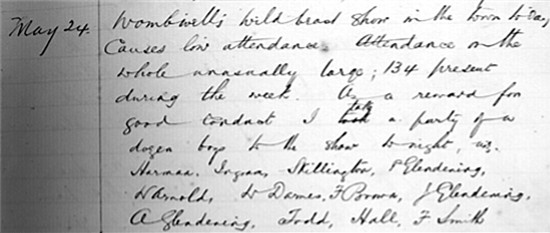

Entertainment and other diversions were also reasons why children stayed away from school, notably in April 1879 when a circus arrived in the town. So few children turned up for lessons on that day that they were sent home and a holiday declared. In December 1887, a menagerie arrived in Bourne resulting in another low attendance and two years later, a cheap rail day trip to Spalding to see Barnum's show and circus attracted many schoolchildren from the town who played truant to attend. Attendance in the face of such distractions could bring their rewards because on 24th May 1881, the log book recorded: "Wombwell's Wild Beast Show in the town today. Causes low attendance. Attendance on the whole unusually large; 134 present during the week. As a reward for good conduct, I take a party of a dozen boys to the show tonight." The visit was obviously beneficial because on another occasion, the staff, while yielding to the inevitable on such occasions, tried to arrange something of educational value from the presence of these travelling showmen and on 1st March 1912, the log book records that classes were dismissed at 3.40 pm "to allow children to attend a large menagerie where the manager gave a description of the animals." On 9th November 1902, the log book recorded: "On Wednesday afternoon, a circus in the town caused a fall of 50 in the attendance. In every case, save one, written notes were sent to me by parents. In the exception, the boy's father had inflicted punishment for truancy." Other annual events in Bourne kept children away from the classroom and the entry for 8th May 1890 reads: "Wednesday being the May Statute hiring fair, a holiday was given. Children were dismissed on Thursday afternoon before the time specified for closing registers as the attendance was miserably low." The log book also provides examples of the practical lessons introduced by the staff, as illustrated by this entry from 20th May 1882: "Last night for home lesson [homework], I asked the upper standards to get as many specimens of leaves as could be found in the hedge and ditch along the West Road as far as Bell's stile. There were many full collections, G Mason gathering 50 specimens and A Glendening's collection was more carefully arranged. Last week or two, I have given a weekly examination and awarded a small prize such as a patent ink-pencil, a knife etc, to the one boy whose paper has greatest care, being neat, well written and correct throughout." By the late 19th century, new technology was beginning to make its appearance in the classroom for the benefit of teachers who had few text books while the pupils often had slates. But the log book entry on 9th January 1885 recorded: "Mr Chadwick has made us a very useful copying machine which with little trouble will copy notes for a class. In this way, compound tenses, lists of auxiliary verbs, pronouns etc have been made for the upper standards. The poetry has been copied too and learned for home lessons." School furniture and fittings, however, remained primitive, and the entry for 10th October 1885 noted: "Farrar (Standard I) trapped his finger very severely in a desk this morning. Our desks are by no means as safe as might be and their construction allows several possibilities of trapping in one way or another." There were other accidents, some of them serious, such as that recorded in the log book on 25 July 1904: "I am sorry to record an accident today that happened to Frank Stubley (12) after twelve in the playground. He had climbed (against orders) up the spouting to get a ball and was walking along the spouting when it gave way and he was thrown to the ground. Mr Butler picked him up and I was sent for from the 2nd Standard room . We placed him in the porch. He was bleeding from the mouth, from a bad wound and was unconscious. He gradually came round and we had him wheeled home under nurse's care. Dr [James Watson] Burdwood was at once in attendance. His wrist was broken and his head slightly injured. I have warned boys against climbing." Compulsory schooling was still hard for some parents to grasp, many regarding their children, particularly boys, as unpaid labour or additional wage earners. An unpleasant encounter with one parent was recorded on 23rd May 1881: "The father of the boy Joseph Parrish called yesterday and asked if his son, who is only in the second standard, could go to work. I told him that he could not do so until he had reached his third standard. The man went away in a violent passion saying that he would never let him attend any examinations but would send him out of the town at examination time." At the boys' section of the school, varied factors were the cause of absenteeism. In July 1877, "market day" caused a low attendance and in the following month it was "the church choir trip to Matlock". In January 1878, when temperatures had dropped below freezing point, boys were soon "skating on Watson's pit" rather than attending to their studies while at the end of April 1880 they were attracted by a battery of artillery which halted in the town and was soon surrounded by a crowd of curious schoolboys, all absent from their lessons. There was more ice skating during freezing conditions early in 1880 although the headmaster appears to have taken a tolerant view of boys being absent for this purpose because the entry on January 29th reports: "Attendance very low today. Many boys away skating and the ice is perfectly safe and they fear the frost will not continue too long. Cold weather always increases the attendance as there is no work then for the boys but when the ice becomes perfectly safe, a dozen to twenty boys are absent every noon with leave from their parents to go skating. Skating is a passion with Lincolnshire boys and indeed men."

Treats or outings organised by local churches were also a distraction from

school but on those occasions, an official half-day holiday was usually

declared. In September 1878, the headmistress of the girls' school noted: "Half holiday on Wednesday, in consequence of a picnic to the wood for

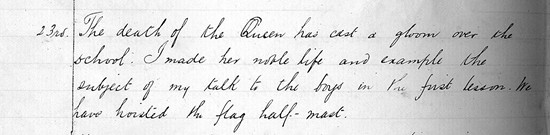

the Band of Hope children. A very low attendance in the morning." In 1901, the death of Queen Victoria brought a wave of national mourning and the log book entry for January 23rd gives an insight into the loyalty she had inspired: "The death of the Queen has cast a gloom over the school. I made her noble life and example the subject of my talk to the boys in the first lesson. We have hoisted the flag half-mast." Holidays were also given for the coronations in 1902 and 1911, and in an intensely patriotic age, war time successes were unhesitatingly celebrated in the schools. Thus, between March and May 1900, Bourne schoolchildren enjoyed no less than three spontaneous half-holidays for major events during the Boer War, celebrating the relief of Ladysmith, Mafeking and Pretoria respectively. And on a June day in 1902 "Mr Wherry [from the school board] came into school at 9.45 am and the schools were then closed for the day, owing to peace being proclaimed."

Throughout the Great War of 1914-18, there are frequent references in the log book to old boys who were now serving with the armed services in France and elsewhere. Mr Davies kept in touch with many of them by writing and receiving letters which he often shared with the boys and staff at assembly. On 23rd October 1914 he recorded: "Read several letters of old boys in the army and navy now on active service. One letter, from a French gentleman, Monsieur E Marie Lefebre, who lives near Amiens, sent to Mrs Kettle (widow), of Eastgate, states that he had met Sgt Stephen Kettle and his brother by great chance, men of Bourne, brave, who have been in the fighting line from the first, and who had helped to capture six guns from the enemy. Stephen and William Kettle are old boys of this school." On 2nd January 1915, the headmaster noted that "over 100 old boys names are on our Honours Roll." Casualties among old boys were inevitable and the log book recorded on 18th March 1915: "I deeply regret to state that news has been received of two old boys at the front being killed, Wilfred Watson, Royal Rifle Brigade, and John Jarvis Smith, 1st Lincolns, both thoroughly good lads in their school career. Several old boys who were wounded in the early battles have called at the school before returning to the front." The entries were to become a frequent occurrence but others recorded the resilience and bravery of some old boys. On 13th March 1916, the headmaster wrote: "Pte 'Prim' Phillips has been recommended for the DCM by Sir Ian Hamilton for gallant conduct in the Suvla battles in one of which he rescued a wounded officer and returned to bring in wounded comrades under gun fire of the enemy. Phillips was wounded in the Ypres fighting (he was with the Grenadier Guards), discharged from Netley Hospital as unfit for service in July 1914: immediately re-enlisted under the name of his cousin, George Mason, in the 5th Dorsets and was at once sent out with that regiment to Gallipoli." Many former pupils also called in while on leave and some spoke to the boys of their experiences. An entry on 28th February 1917 records: "Almost every week, old boys from the front visit the school and receive a hearty welcome. They said a few words to the boys. Sidney Brown came in; I am proud to note that for special courage under danger, rescuing a fallen comrade under fire and bearing under very trying conditions at a critical time, a message safely to the general of a French company, Sidney Brown has been awarded the Military Medal and Croix de Guerre."

Another military honour was recorded on 25 April 1918: "I

am happy to note the following: Corporal Matthew Michelson (transport

section of the Lincolns), for splendid devotion to duty while taking

ammunition to the front, has been awarded the Military Medal." "This morning, in accordance with the King's request, a two-minutes' silence in reverence for the memory of those who fell in the Great War was observed. This was preceded by a brief address, the reason of this silent ritual of two minutes' silence for five years of remembrance of the fallen of the armies and of the unhealed wounds of war. Especial note was made of the names and memory of our many Brave Old Boys who gave their lives. After the reverent pause, the boys recited 1.Cor.XIII; sang the verse: "Far-called our navies melt away; Teach us the strength that cannot seek by deed or thought to hurt the weak." and recited Longfellow's "The Arsenal"; sang the hymn "O God of Peace" and Lowell's "Englishmen, who boast that ye come of fathers brave and free" and recited various selections on "Peace"; thus leading to another brief address on the aim of the League of Nations. The King's letter advocating the cause of the League was read." The peace proclamations for the Great War are also recorded in the infants' school log book for 11th November 1918 when the headmistress wrote: "Afternoon. News received that Armistice has been signed. The children, with the help of the caretaker, made a bonfire in the playground to celebrate it." The celebrations seem to have been either exhausting or prolonged because the log book for the following day records: "There were no children at school today and so the teachers all went home."

But despite the many holidays and unofficial breaks from school, teaching

and learning did proceed with great enthusiasm with many children

turning up regularly and making good progress, and by 1900,

figures had improved considerably. In 1907, an average weekly attendance

of over 90% was not uncommon in the girls' school and in the infants'

school, even in that unusual week of the 1918 armistice, the average was 76% while reports from the school inspectors generally

spoke highly of the standards achieved.

There seems little doubt that the good progress of both the girls' and the boys' schools was largely due to the character and ability of their respective head teachers. From 1880 to 1920, Miss Clara Ward was headmistress of the girls' school. She was a strong disciplinarian who was remembered by one of her pupils as being very keen on the teaching of grammar and whose devotion to her work is manifest in the entries she made in the school log book over a period of forty years.

On a February

afternoon in 1920, Miss Ward received a farewell presentation from

managers, staff, children and "Scholarship girls now attending Stamford

High School". On that day she wrote: "February 27th 1920. I resigned my

post as headmistress of this school, and must express the regret with

which I part from all connected with it, for I have received unqualified

kindness from everybody during the many years I have been here." To the farewell presentation from pupils and staff, Mr Davies replied by a letter which was read to the assembled school, and the comment by a journalist who was present conveys the atmosphere of the occasion: "The reading of the letter caused a profound impression, for it is not too much to say that the boys loved their master."

Mr H E Sharpe took over as temporary headmaster when school

reopened on 20th September 1920 pending a permanent appointment which was

eventually filled by Harry Goy, a former pupil teacher, but conditions had

declined during this period, a reflection no doubt on the efficiency of Mr

Davies, and his first entry in the log book on November 1st said: "The

school is in a very neglected state. Discipline is lax. No scheme of work

can be found. Stock cupboard is practically empty. I am therefore

formulating a scheme of work to carry on until Xmas." "During playtime this afternoon, Philip Longland sustained a severely cut wrist. Not knowing that his friend was just closing his pocket knife, he commenced to spar and caught his wrist on the knife blade. I immediately bound up the wound and then took the boy to his own doctor. Three or four stitches were needed. After treatment, I took the boy home and reported to his mother." Hundreds of boys and girls were evacuated to Bourne during the Second World War of 1939-45 to live with local families to escape the bombing of their home town. The majority went to the Abbey Road school and despite being accompanied by several teachers, this put pressure on space and facilities. On 8th July 1940, the headmaster reported: "We are now to work on a double-shift system. It has been decided to arrange a weekly change over. In the 'off' sessions, the various halls in the town are to be used and full use is to be made of the recreation ground and the local football ground for physical training and organised games. Nature walks and educational rambles will also be arranged."

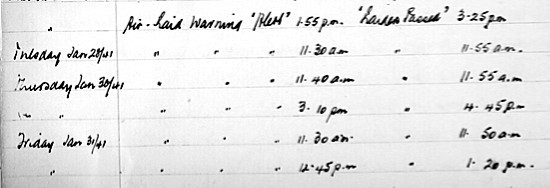

There were other signs that Britain was at war and an entry on 1st May 1941 said: "This is Bourne and district War Weapons week. An armoured train is on view at the railway station. I am arranging that the children be taken to see it, girls in the morning, boys in the afternoon." Air raid warnings often sounded as enemy planes passed overhead when the school was evacuated to adjoining air raid shelters that had been specially built but the effect on pupils could be alarming, as was recorded on 14th May 1941: "Alert at 1.45 pm. At 2.45 pm, I took the responsibility of bringing the children back into school. The shelter accommodation is very inadequate when all the children are on the school premises and several girls were on the verge of collapse. Raiders passed 3.15 pm."

Then on 29th May 1945, came the welcome relief with the entry: "In

continuation of VE [Victory in Europe] celebrations, all the

schoolchildren are being entertained in the Corn Exchange tonight. They

will meet at the school at 5.30 pm." And on June 28th: "Hull evacuees

returned to Hull today." "The school is now working well. Both the new children from the villages and the Bourne children seem happy together. The staff have worked with enthusiasm and I am confident we shall do well." There were still the occasional problems with staff, particularly the new PT and games mistress, Dr M Nentwich from Vienna, who had been engaged in September 1949 for one year. But on 8th November, the log book entry states: "Miss Nentwich came to school this morning wearing breeches and high boots. I asked her why and she replied she was cold taking games and that she intended to continue wearing the costume. I requested her to go to her rooms and change into suitable attire for the physical training to be taken in the Vestry Hall. She went away and has not returned to school until today, having interviewed the Director of Education at Sleaford. The correspondence of this case will be found in the staff file."

The outcome of this confrontation is not known because the

staff file has been lost and there are no further entries in the log book

relating to Miss Nentwich. "Speech Day and a dedication of the new building by Canon D S Rowlands, vice-chairman of the governors, and a plaque was unveiled by the Earl of Ancaster, the Lord Lieutenant. Including 200 children, the ceremony was attended by 620 people. A memorable, happy occasion. - L R W Day." Mr Day retired on 31st August 1968 and was succeeded by Howard Bostock by which time log book entries were now reflecting the modern educational system we know today, with school trips abroad, outings and skiing holidays for pupils accompanied by teachers, staff training, musical productions, parent evenings, meetings with local employers, visits by businessmen and the local M P. There is one notable entry on 10th October 1972 when Mr Bostock recorded in the log book: "From 10th October to 8th November, the school was a staging centre for Asians who had been evicted from Uganda by General Amin. The Asians landed at Heathrow, Stansted and Gatwick, and came up to camps at Hemswell and Foldingworth. Altogether, 2,400 Asians came through Bourne, the youngest being twelve days old and the oldest 87 years. The WRVS provided the food and it necessitated me being on duty continuously for almost twenty four hours each day. For several nights, I slept at school."

Louis Decamp took over as headmaster on 12th May 1980 and

continued until 3rd April 1984 when he wrote: "Visit from the chief

inspector to say goodbye. It begins to register that time is short." He

was succeeded by Michael Kee on April 30th and it was he who made final

the entry in the log books on 13th July 1990 which related to pupils being

given work experience, a reminder of how the educational climate had

changed since the Victorian era.

WRITTEN FEBRUARY 2012 See also Death in the playgound The punishment book

Go to: Main Index Villages Index |