|

A HISTORY OF GRIMSTHORPE CASTLE

By JOSEPH

J DAVIES

Reproduced from his book Historic Bourne published in 1909

Grimsthorpe Castle pictured at the

turn of the 19th century

by the Bourne photographer William Redshaw

Grimsthorpe Castle, the seat of the Right Hon the Earl of Ancaster, commands an extensive view of picturesque scenery. It is four miles NW by W from Bourne, and is near the northern end of a magnificent park of about 2,000 acres, four miles in length by about two miles

in breadth. The park, which is said to be 16 miles in circuit, has a beautifully diversified surface of hill and dale, woodland and lawn. There are some grand old oaks and hawthorns, and a splendid avenue of chestnut trees. The south end embraces a deer park of about 1,200 acres. The large herd of fine red deer are of the original race which in ancient times roamed wild through the forests of Britain. A lake adds to the charm of the scenery. An interesting memento of the Cistercian Monks is their fish pond snugly hidden in a remoter nook of the park.

Near by the site of the Abbey, a stream suddenly disappears and does not emerge until some distance beyond the park boundary. This phenomena is occasionally observable in limestone districts. The stream has dissolved

for itself an underground course. In Spain the instance of Los ojos de Guadiana is familiar. In Greece similar cases occur, these being doubtless the origin of the legend of:

Divine Alpheus, who by secret sluice,

Stole under seas to meet his Arethuse.

The most ancient part of the castle is the massive embattled south-east tower, probably of the time of Stephen. The walls are of immense thickness, and batter as they ascend. It contains three rooms, one over the other, access to which is given by a small winding staircase. The original structure was irregular in form. The greater part of the mansion is a spacious quadrangle, and the principal portion was built and the park laid out by Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, one of the favourites, and in marital adventures, an illustrious follower of his Royal patron, Henry VIII. The Duke of Suffolk, upon the death of his third wife (Mary, Queen of Louis XII of France, and sister of Henry VIII), married his young ward, Catherine, tenth holder of the Barony of Willoughby. To her father

William (on his marriage with Mary de Salinas, a Spanish lady attendant upon Queen Catherine of

Aragon), Henry VIII had granted these manors of Grimsthorpe and Edenham, which formed part of the estates of Lord Level, forfeited through treason.

"Before the young Duchess of Suffolk's time," Leland says, "the castle was no great thing, apparently an old stronghold, surrounded by a moat, protected by a fair and strong gatehouse, and embattled walls of stone." Naturally, (says the late Dr Trollope, Bishop of Nottingham) this was insufficient for the accommodation of so great a nobleman as the Duke of Suffolk, after his marriage with the young Lady Catherine, the Willoughby heiress. So it was rebuilt on a grander scale, more after the style of a palace than an old castle stronghold. The work was completed in haste, to entertain King Henry VIII in 1541 during his royal progress through Lincolnshire. Fuller therefore calls it an

extempore structure. The great hall built at this time was then hung with tapestry which had come into the Duke's possession through his third wife Mary Queen of France, King Henry's sister. The Duke's royal brother-in-law was entertained at the Castle from August 5th to 8th, 1541, when he continued his "progress" among his people of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, after the suppression of the rebellion of the "Pilgrimage of Grace," aroused by the dissolution of the smaller monasteries. Upon the Duke of Suffolk's death, in 1545, his young widowed duchess openly befriended the Protestant Reformers, and was known as a "Nursing Mother of the Reformation". She entertained Latimer and other religious leaders at the Castle. In 1552 the Duchess married Richard Bertie, a Kentish gentleman, and an accomplished scholar, and the following year, upon the outbreak of the Marian persecutions, they sought refuge on the Continent. Peregrine was born at Wesel, during their wanderings: hence his name, as the register of that place shows:

Eo quod in terra peregrina pro consolatione exilii sui piis parentibus a Domino donatus sit.

On the accession of Elizabeth they gladly returned to Grimsthorpe. Peregrine, their son, (died 1601) who succeeded as the eleventh Baron Willoughby de Eresby, was one of the most famous military leaders of Elizabeth's reign. He was the gallant commander of the English contingent sent to France by Elizabeth to aid the Huguenot cause under Henry of Navarre (the hero of Ivry) who in acknowledgement of his services presented Peregrine with a table diamond ring,

which is still preserved in the family. He was the friend of Sir Philip Sydney, and after the battle of Zutphen, upon the Earl of Leicester's recall, he was made General of the English forces in the United Provinces. It was during this campaign that the famous battle took place which is immortalised in one of our most stirring British ballads, preserved intact in

Percy's Reliques, called . . .

|

THE BRAVE

LORD WILLOUGHBY

The fifteenth day of July, with glistening spear and shield,

A famous fight in Flanders was foughten in the field;

The most courageous officers were English captains, three,

But the bravest man in battle was our brave Lord Willoughby.

With fifteen hundred Englishmen, alas, there were no more!

They fought 'gainst fourteen thousand men of Spain on Flanders' shore.

A resolute stand and a final glorious charge, result in the utter

discomfiture of the enemy.

"Stand to it, noble pikemen! And look you round about,

And shoot you straight, ye bowmen,and we will drive 'em out!

You musket and caliver-men, as you prove true to me,

For England's honour, God and Right, on!" cried Lord Willoughby.

For seven long hours in all men's sight this fight endured sore

Until our few so wearied grew, they scarce could fight on more

War-worn, hard-pressed, sore-famished, they are undaunted

yet-

Hurrah! the Spaniards waver, hurrah! hurrah! they flee,

For they feared our English yeomen who fought so gallantly,

And they feared the stout behaviour of the brave Lord Willoughby.

"Haste!" cried the Spanish general, "Come, let us haste away,

I fear -we shall be ta'en or slain, if here we longer stay.

Lord Willoughby and his English come, with courage fierce and fell,

They will not yield one inch of way for all the fiends of hell."

And then the fearful enemy was quickly put to flight;

Our men pursued courageously till fell the shades of night.

When Queen Elizabeth received tidings of the famous victory she gave

him gracious praise, and declared that-

The brave Lord Willoughby our love hath nobly won,

Of all our lords of honour none nobler deeds have done.

The ballad ends with a dauntless note in the true old British vein-

Then courage, noble Englishmen, and do not be afraid,

For if we be but one to ten, we will not be dismayed. |

Peregrine married Mary de Vere, daughter of John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and Grand Chamberlain of England. Their son was Robert, the 12th Baron, who claimed the Earldom of Oxford and the Great Chamberlainship, the latter being allowed. Charles I, however, created him Earl of Lindsey in 1626, Knight of the Garter in 1630, and on the outbreak of the Civil War appointed Robert Commander-in-Chief of the Royal forces. He was mortally wounded at Edgehill, when fighting gallantly for his King. (His is one of the beautiful monuments of the Willoughby family to be seen in Edenham Church where the war-dented helmet actually worn by him at Edgehill is also preserved. Other monuments of the family may be seen in Spilsby Church.)

Montague (who fought at Edgehill) succeeded as second Earl Lindsey. His grandson Robert, the 4th Earl, was created Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven in 1715. He was succeeded by his son Peregrine as 2nd Duke. It was this Peregrine, Duke of Ancaster, who employed

Vanbrugh to reconstruct (in 1722-3) the north front of the castle on a more dignified and magnificent scale. The architectural character of this imposing structure, however, is not in harmony with the Tudor edifice of which it forms an extension. Still

Vanbrugh's work fulfils his intention of imparting an added grandeur to the famous fabric. "Its principal front, facing north," (says Dr. Trollope), "consists of an imposing central feature with large windows, and a stately entrance, surmounted by a balustrade, vases, and a large shield of arms, flanked by square towers, having circular chimneys at the angles. In front is a square court enclosed by solid walls with dwarf towers at its outer angles, an arrangement which materially contributes to the dignified appearance of the exterior. The Great Hall occupies the large part of the centre of the north elevation. On the left of this, in the west wing is the spacious chapel. The corresponding wing constitutes the drawing room, facing the east. The other principal rooms occupy the remainder of this elevation, comprising three drawing rooms, the Suffolk room - the old angle-tower of the former edifice (now known as the "bird-cage tower") which boldly projects from the castle.

The castle contains many objects of rare artistic and historic interest. The coronation perquisites of the Lords Willoughby de Eresby, as hereditary Great Chamberlains of England, are of unique interest. These include the coronation chairs and royal canopies of George I, II, III, IV,

and of Queen Victoria, and the table used at the Queen's Coronation. There are also preserved the coronation robes, and gold plate of great value. The state drawing rooms contain a large number of family

portraits and those of the Kings and Queens of England from an early period, presented by the reigning sovereigns to the Lords Willoughby

de Eresby. Among the most valuable paintings are one by Velasquez (in the Chapel); Charles I and family (by Vandyck); James I, in his Coronation robes, (James I was entertained in the Castle on his royal progress from Scotland to Westminster in 1603); Montague Bertie (by Vandyck).

There are several portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Reynolds in the State dining room has a pathetic interest: it is said to be the last painting of Sir Joshua's. The collection is especially rich in Holbeins. In the dining room are no less than seven productions of this old master,

including portraits of Henry VIII, Francis I, and one of the artist himself. Hogarth is represented by two paintings,

Noon and Afternoon from his series The four times of the

day painted in 1738. There is a fine portrait of the heroic Elizabethan General Peregrine, "The brave

Lord Willoughby". For the purpose of classification this fine collection of pictures may be divided into five groups:

|

1. Family portraits of the former inhabitants of Grimsthorpe and their

relations, through successive generations.

2. Portraits of Royal personages.

3. Genre pictures.

4. Landscapes representative of various National Schools.

5. Sporting pictures, and pictures of animals.

|

The very fine collection of portraits in oils includes the Kings and Queens of England, and famous family portraits of the Earls of Lindsey and Dukes of Ancaster.

Particular interest attaches to an excellent portrait of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk (1484-1545), son and heir of William Brandon, Henry VII's standard-bearer, who was killed by Richard III on Bosworth Field. Charles Brandon, as stated above, was a favourite companion of

Henry VIII, and on the death of his wife Mary (sister of Henry VIII and ex-Queen of Louis XII) married his ward Catherine Willoughby. In 1541, he entertained at the castle the King and his wife, Catherine Howard.

In the Sporting Gallery are pictures of famous racehorses belonging to the Dukes of Ancaster. There is also a painting of the Flemish horse upon which Charles II was mounted when he received a historic deputation in 1660.

A portrait of Lady Jane (Grey) Dudley, eldest surviving daughter of Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset, Duke of Suffolk, by Frances, daughter of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and his wife Mary Tudor, sister of Henry VIII. Portrait of Charles 1 and Henrietta Maria, with James, Duke of York (afterwards James II), and Mary (afterwards Princess of Orange); by Sir Anthony Van Dyck (about 1639).

There is a fine collection of religious subjects after Titian, Correggio, and in the style of David Teniers and Rubens.

The Dutch school of the 17th century is well represented, as are the Italian and German Schools.

The famous Gobelin tapestry already alluded to is in the state dining room and the tapestry in the state bedroom is especially fine, and doubtless formed part of some Royal collection. There are many fine miniatures, those of the Stuarts being famous; they were loaned to the recent Franco-British Exhibition, and attracted much attention. There is also valuable statuary, and collections of china. Among the many interesting historic relics preserved in the castle, may be mentioned the original thickly padded dress worn by James I, depicted in his portrait. Lovers of art will admire the elegant chimney piece in the centre state

drawing room. Under the cornice are three basso-relievos in white marble, the centre one representing Androcles pulling a thorn from a lion's paw.

Other treasures include the state chair and footstool used by King George III in the old House of Lords from 1803 to 1810; the gilt state stool used at the Coronation of George III, Sept. 22nd, 1761; the gilt state chair and footstool used by King George IV at the Coronation banquet, July 19th, 1821; the gilt state chair and footstool (for use in the old House of Lords from 1842-1847) of Albert Edward Prince of Wales (King Edward VII); a wonderful set of 16 chairs of oak, with curved backs, coloured white, painted in colours, with coat-of-arms under a ducal coronet, with supporters, arms, crest, motto

(Loyauté m'oblige) and initials of Peregrine, second Duke of Ancaster (died 1742). The chairs are of English work between 1723 and 1742. There are also mementoes

of the visit of the King of Denmark who, in 1768 was magnificently entertained at the castle.

Particular value attaches to a wonderful set of tapestry-panels, each representing the triumph of a god, the classical themes embracing Apollo and the Muses on Mount Parnassus, Neptune, Flora, and Diana. There are also three panels of tapestry, eighteenth century work, each representing a Dutch subject in the style of David Teniers. Among the other objects of interest are beautiful chandeliers and girandoles or wall-lights.

Within view of the Castle, and near the lake, existed the Cistercian Abbey,

Valle Dei (Vaudey), in a secluded vale. This Abbey was founded "to the Glory of God" in 1147, by William le Gros, 3rd Earl of Albermarle. Gilbert de Gaunt was a munificent benefactor to it, and Ganfred de Brachecourt endowed it with his estate here, on condition that the brethren should maintain himself, his wife and two servants during their lives, granting them a double allowance. It is said to have been translated from Bytham, and colonised from Fountain's Abbey, in Yorkshire.

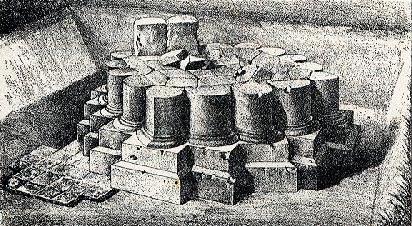

View of a pier of Vaudey Abbey in

Grimsthorpe Park

The house was for thirteen brethren of the Cistercian Order. At the dissolution their lands were valued at £177 15s. 7d. a year, though these same lands in this and neighbouring parishes are said to be worth about £3,500 a year. The Abbey was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. Scarce a trace of the house now remains. The site is overgrown with trees. In 1852, the grass and earth overlying the foundations were removed, and some idea could be formed, from the bases of cluster-pillars and other traces, of the former extent and magnificence of this once flourishing religious institution. The house and lands at the dissolution were granted to Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who married his ward, the young Baroness Willoughby, through whom the estate passed into the family.

A coat of arms of James I is built into the wall of a farmhouse at Scottlethorpe, now occupied by

Mr George Levesley. This farmhouse is on the opposite side of the road to the Old Manor House, and a little nearer Edenham.

The date of the old (and now demolished) Manor House at Scottlethorpe is unknown, but it was probably either late Elizabethan or early Jacobean. The coat of arms over the doorway was that of Robert, Earl of Lindsey, the leader of the Royalist forces, who was killed at Edgehill,

October 23rd, 1642. He was buried in Edenham Church, where his war-battered helmet may be seen. This coat-of-arms is now built into the wall of the castle, over the doorway on the Tudor side.

It is said that Henry VIII visited the Manor House. James I was entertained here.

The present stables probably were once part of the ancient chapel. They contain a fine Norman arch.

Formerly an old roundhouse stood in the park, almost in a line with the old coach road (the paving of which may still lie seen in some places), that runs through the Bishop-hall.

The curious old house with a tower, in Swinstead, not far from the residence of the Hon Miss Willoughby, was built by Brownlow, the fifth Duke of Ancaster. It was originally a gateway to his gardens. The Duke said he was too poor to live at Grimsthorpe. He therefore shut up the castle, and spent a large sum in building a house at Swinstead, with

fine gardens. Of this house there is little extant. He was the last Duke of Ancaster.

Reverting to the romantic career of Catherine, Duchess of Suffolk, we may note a pathetic episode that demonstrates her loyalty to her friends. This was her adoption of the orphaned and portionless daughter of her honoured friend Queen Katherine, surviving wife of Henry VIII. The

Duchess had edited the devotional writings of the Queen.

Readers of history will recollect that, within a few months of her royal husband's death, Queen Katherine married Sir Thomas Seymour (Lord Sudley, the Lord High Admiral of England). In August 1548 the Queen Dowager gave birth to a daughter, Mary, at Sudley Castle, but within a week of this event, the Queen died. The ambitious admiral's intrigues for supplanting his powerful brother, the Protector Somerset, in Edward VI's favour, led to his disgrace and execution in the following March. His dying request was that his high born infant should be taken to Grimsthorpe Castle, and placed in the care of her royal mother's faithful

friend, the Duchess of Suffolk. The unoffending child had already been cruelly robbed of its rights, being disinherited by an Act of Parliament. Its uncle, Somerset, and the Queen's brother - the child's natural guardians -refused either to shelter the orphan, or to vindicate her rights. Indeed, they plundered the little one of her princely inheritance. But Catherine, Duchess of Suffolk, took the destitute orphan under her care, and became as a mother to her. The little Lady Mary Seymour, thus kindly nurtured by the Duchess, appears to have married an honourable gentleman

of the court, Sir Edward Bushell. (One writer, Lodge, however, states that the Lady Mary Seymour died in her thirteenth year; but this statement is unsupported by authority).

Among the State domestic papers (from 1546) are many letters addressed to Catherine, Duchess of Suffolk, to her Bourne neighbour and loyal friend, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, one of the most powerful patrons of the Reformation. This interesting correspondence ranges over a

variety of topics, from Grimsthorpe and Lincolnshire gossip, and appeals for advice in business affairs, to critical religious questions, and matters of State importance.

The Earl of Ancaster, originally by descent Gilbert Henry Heathcote, but since 1872, Heathcote Drummond Willoughby, inherited the Baronetcy and Barony of Aveland from his father, and the historic Barony of Willoughby de Eresby (dating from 1313), and his office of Joint Hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain of England, from his mother. He was born in 1830, succeeded his father as second Baron Aveland in 1867, and

his mother as twenty-fourth Baron Willoughby de Eresby in 1888. He was educated at Harrow, and Trinity College, Cambridge.

The Countess of Ancaster was Lady Evelyn Elizabeth Gordon, second daughter of the tenth Marquis of Huntly. The family motto

Loyauté m'oblige admirably epitomises the noble characteristics of this ancient and illustrious house, whose honourable traditions are maintained in most active, public spirited and generous measure by the present

Earl and Countess.

See also

Theft at

Grimsthorpe Castle Fire

at Grimsthorpe Castle

The

Earl of Ancaster

Thomas Linley Scottlethorpe

Edenham

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|