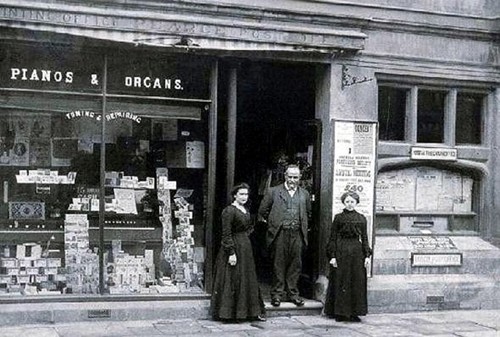

The piano was an essential feature in many middle class homes during Victorian times. Parents and elder children played to give pleasure to themselves and others and although practising was often purgatory for the younger ones, the overall benefit was one of music making in the home that soon spread to the public platform at concerts in local halls and churches. This was a time before the arrival of radio, television and the Internet when gatherings round the piano were a regular occurrence on Sunday evenings, on birthdays and at Christmas, to hear family and friends play their party pieces and the tunes of the day to which everyone would join in and there could be nothing more enjoyable than the spontaneity of such occasions. The modern piano is based on the mechanisms of earlier keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord and clavichord and was invented in Italy during the 17th century with the result that they were soon being made throughout Europe. The instrument was perfected over the years to that which we know today, giving a more powerful and sustained sound, a development made possible by the Industrial Revolution which produced resources such as high-quality piano wire for strings and precision casting for the production of iron frames which enabled the strings stand on end rather than flat, thus enabling the use of a smaller wooden case. As a result, thousands of sturdy uprights were manufactured during the 19th century and this allowed ordinary families to buy one for the home, thus heralding a new era in music making within the family circle. They were soon on sale at shops throughout England and even the smaller towns such as Bourne boasted a dealer that could not only sell you a piano but also the sheet music to go with it to enable the owners play both classical music and the songs of the day that were being popularised by the music halls and even whistled in the streets by errand boys. William Daniell was an enterprising businessman who saw the potential in piano sales. He already had shop premises in the market place at Bourne where he ran a printing and publishing business although his shop also provided a wide range of other goods and services and in the early 19th century he decided to open what he called a music warehouse with a large number of pianos for sale. He travelled to London to obtain his original stock and having brought eight instruments, both new and second-hand, had them transported back to Bourne where they were put on sale in April 1832. They were all attractive six octave models in rosewood or mahogany cabinets, French-polished and fitted with silk curtains at the front, and bearing such famous names as Wornum, Broadwood, Preston and Stodart, and priced between ten and 50 guineas, one guinea then being worth almost £100 at today’s values. An example of Daniell’s descriptive powers in his advertisement demonstrates that he knew how to sell: “I submit the following list of pianofortes for the inspection of those of my musical friends who may wish to supply themselves with one of these pleasing companions”, he said and there followed a list of his available stock, each one lovingly described in great detail such as with this example: “A 6-octave cottage piano of the most beautiful and pleasing tone, in a mahogany case, by Wornum, priced at 36 guineas. This is one of those delightful little instruments called the Picolo, so eagerly purchased in London and admired for their portability and sweetness of tone which is offered at the maker’s own price.” The pianos were soon sold and Daniell bought more replacement stock to continue his new line in business, the buyers being the more affluent of Bourne’s citizens with wives and daughters who wanted to learn to play to entertain the family at home and at the various concerts and soirees which then formed part of the town’s social life. Although heavy, the pianoforte, as it was grandly known, was portable and could be moved around to figure prominently on all such occasions and there was always someone prepared to play, either to accompany a singer or to give a recital. Daniell closed his business and left Bourne around 1850 but the piano trade survived through the Pearce family, Edward followed by his son John, who traded from premises in North Street where they continued to sell the instruments which remained in demand well into the 20th century. The popularity of the piano in the home, however, declined with the arrival of television and the electronic age which produced new keyboards that were lighter and less bulky and soon the old Victorian models that had seen regular use in homes, public houses and clubrooms, had become redundant. Few wanted them when they appeared in the salerooms because the iron frames made them heavy to move and they looked out of place in the modern home. As a result, thousands were destroyed during the 1950s, many ending up in piano breaking contests at garden fetes, festivals and other local events across the land when they were smashed to smithereens by teams of burly men wielding sledgehammers. The piano has retained an important place on the concert platform but the rosewood and mahogany models of past times that were once regarded with such affection are no longer as popular as they were although still a healthy market for them at specialist shops for the collector or connoisseur while those instruments that do survive in the home are smaller, lighter, more graceful and sometimes even electronic, although many of those now gather dust as their owners seek their entertainment elsewhere.

Go to: Main Index Villages Index |