|

A

glimpse of Bourne in 1871

|

In the summer of 1871, Mr Robert Mason Mills,

founder of Bourne's thriving aerated water business, invited a

reporter from the Peterborough Advertiser newspaper to

visit the town as his guest. He took him on a tour of the locality,

and of his own business in West Street which was then achieving

national fame, and gave him dinner at the Bull Hotel, now the

Burghley Arms, all part of the system which we know today as

public relations. The subsequent report which the journalist wrote

for his newspaper sounds rather naive today but it gives us a

remarkable insight into Bourne as it was almost 150 years

ago. |

BOURNE AND ITS MINERAL WATERS

Our long settled, well cultivated, "merrie England" has many spots of beauty within its wide limits. Will the reader accompany us to one? It is not far away.

A little north of Peterborough, the Great Northern railway makes a triangle which may be roughly described as having its apex at Peterborough, and its base from the Essendine junction to Bourne, or Bourn - as it is called by those who adopt one theory or another as to the origin of the name.

This line, which from Essendine runs eastwards to Lynn, traverses a pleasant country. It is tolerably well-wooded, and the meadow and arable are mostly rich; and at this delicious season of the year the whole route is, as it were, through the glades of a park. Bourne itself - for that is the manner in which we propose to give its name - is favourably circumstanced. Lincolnshire is not all fen. The land rises in wolds in many parts of the county, which wolds - though long ago reduced to subjection by the agriculturist - nevertheless pleasantly diversify the countryside with hill and dale.

Bourne is on the eastern declivity of one of these ranges, where the land sinks into the fen that extends right away to the waters of the Wash. Our special business there, one recent sunny day, was to see the process of the manufacture of the mineral waters sent out by Messrs. R.M. Mills and Co., of Bourne, who had now established a reputation over the country wherever their pleasant soda and sparkling lemonade is drunk.

Of these waters we shall have more to say by and by; but the many attractions of Bourne put them out of our thought for a time, and the more especially as we found in Mr. R.M. Mills himself an agreeable cicerone, well acquainted with all the details of the history of the town and its many antiquities. It is not possible to stand on such a spot unmoved. There the footsteps press a soil that should be sacred in the eyes of Englishmen. It lies in the heart of woodlands, surrounded by fertile fields, and sheltered by the wold range - quiet and still as

though the discord of war had never silenced the peaceful sounds of the country.

Here, however, the Romans planted themselves by the force of their arms; and this was one of the spots which they reclaimed from the wild. The Car Dyke is one of the monuments of their laborious skill and indomitable perseverance. A map of the county shows its course. It starts from the Welland at West Deeping, and runs northward to the Witham, near Fiskerton, a few miles from Lincoln. When first constructed this was a magnificent work. It was 60 ft. wide, and had a solid raised bank on each side.

Its purpose was twofold. In the first place to catch the flow of waters from the hills which run above its western bank, and to prevent the overflowing of the fens, and in the second to provide a navigable canal. At Bourne the Car Dyke, though it has yet a good channel, has been much filled up, and its dimensions contracted. Just now a new branch railway is being constructed from Bourne to Sleaford and the alluvial deposits of centuries are being removed.

The tesselated pavement of a Roman villa was sometime ago discovered in the park of the Red Hall; and it was not unlikely that other remains would be discovered in the course of the excavations.

Mr Mills, who is profoundly interested in the antiquities of Bourne, keeps a sharp look-out in such matters. The workmen know that such remains as the pick and the plough turn up find a ready market with him; and many are the treasures which he has accumulated. From the Car Dyke excavation he has thus obtained an exquisite Roman relic. It is the upper basin of a fountain, in pottery ware formed of the clay of the district and as beautiful and almost as perfect in form, if not in colour, as when it was turned out of the hands of the potter. The basin is round, and it is about the size of a wash-hand dish, and the under surface from a few inches to the rim is scalloped. The water evidently came through a pipe in the centre of the dish, and probably flowed out of a spout into a larger receptacle. The basin is an artistic production; and, of itself, it is a proof that civilisation in these old days had reached Bourne.

But the little town has another history besides that written upon by the Romans. They dwelt in England for centuries; but their civilisation is a thing of the past, buried under newer traditions as their architecture is, for the most part, under the accumulated soil of their empire; and the Romanised Briton succumbed to the stout Teuton. Through long years Saxon and Dane fought in these eastern regions; and then came the conqueror. No doubt the conquest has ended in good; and we would not undo the work of the robber Norman. England is the proud England of this day because of these early trials by which her people were welded into a strong nation as the iron is tempered in the forge. Yet Englishmen, who preserve the Saxon tradition, feel a strange thrill at their hearts when they think of the Normans, and wish that they had the opportunity of fighting the battle once more.

Who can help that feeling at Bourne? There the traveller stands within lines of the Camp of Refuge, where the English held out to the last. There are few apparent signs or tokens; but that is the fact. We stand in the Castle Field. In that castle Leofric of Mercia fought valiantly if vainly; and in the reign of the Red King it passed to a Norman. The castle is gone with feudalism. The Marquis of Exeter owns the soil, and the ruins that are under the soil; but

now the traveller only treads the green turf as his eye traces the course of the castle-moat, marks the line of a distinct encampment, and his ear receives the story of the still intact dungeons which the grass now covers, and which formed the foundations of the drawbridge.

It was in the time of the late Marquis that the ruins above ground and the ancient drawbridge were finally cleared away. The man who farmed the land preferred grass to archaeology. He did not see the utility of a heap of old stones; and the Marquis had no more respect for one of the most interesting monuments of the country that to yield to his whim, and to allow the stones to be carted away. The present Marquis is a man after a different pattern. He is a conservator of the relics of old times; and he has done much for Bourne, and is willing to do more.

We are in the ground where stood the castle; and near at hand - whither our steps, under the guidance of Mr. Mills, are tending - is the water from whence Bourne must have taken its name. It is the "Well-head". Leland is the authority. He says that a bubbling spring is called Bourne, and a running stream Bourn. There is only the difference of a letter for local antiquarians to break words upon; but if we had to take sides - and we have done - we should stand for the E inasmuch as this fine natural spring is much more striking and much more likely, therefore, to give its name to the place than the stream that flows from it.

Now we stand on the brink, mark it well. What a lovely sight. The water covers about an acre of surface; and the bank is broken into an irregular circle. How clear! How cold! So cold that fish and reptile life has no place in it, as we read of some of the mountain tarns. There is no pollution here. The water bubbles up from seven springs that go down to its source in the cold and "deep-delved earth", and as it comes through the lime stone, it brings with it the small shells from the strata which float on the surface and then sink to the sand at the bottom. To the very depths we see the water. The bottom shelves around the springs until it reaches the depth of 20 feet; and the floor shines as though it were laid with jasper.

It is an exquisitely lovely sheet; and the flow is so constant that it keeps up the current of the Bourne river which runs thence away to the river Glen. Here is a work which the Marquis of Exeter might do. The well-head is bare of trees. If the ground around were planted and ornamented, and if walks were made about it, it would form one of the most delicious fountains in the country, and the baths that could be made would be excellent. Indeed Bourne might be much improved - so much that we can conceive its growing into a watering place to which visitors might be attracted from the remotest corners of the land. Its natural beauty is of a sweet order; the neighbourhood is well-wooded; the waters are such as might tempt the valetudinarian from a German Brunnen; and its archaeology, inwoven as it is with some of the most interesting passages in our history, is an additional attraction.

But "the muttons" must be considered. Our visit to Bourne was with intent to see the manufactory of Messrs. Mills; and thither we turn. The place is in the centre of the pleasant cleanly-looking town. The water which flows up into the wellhead is the water from which Messrs. Mill's artesian Bourne waters are made. Theirs is not the water that comes into the well-head however. They run down into the underground fountains, and take their supplies from the pure and cold reservoir held within the ribs of the earth. The reservoir is 94 feet below the surface, and it rises 39 feet above the surface when pierced by an artesian well, the temperature in winter and summer being 38

degs.

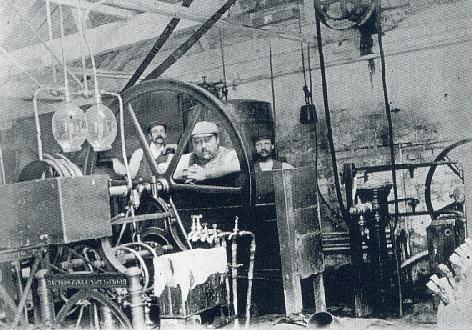

The

bottling plant behind the West Street premises of Mills and Baxter

Messrs. Mill's bore is four inches in circumference; and they have thence a constant supply of water which never mixes with the air until the bottles containing the manufactured waters are uncorked and the contents are allowed to flow into the drinking glasses. It is obvious that the water being of the right kind, this is the perfection of manipulation. Wherever Messrs. Mills's water go to - to the farthest extremities of England, or to lands beyond the seas - the drinker gets the fresh beverage; and we can say for ourselves that any beverage more exquisite in flavour than their soda-water we never tasted. There cannot be a doubt either as to the extent it, and its kindred waters, will be used by all who know them.

From all that we saw we can say that the manufacture is most carefully conducted; and that Messrs. Mills will give a new fame to Bourne. Dr. Parkes, professor of Military Hygiene, thus gives the dissolved matter which should not be exceeded in a wholesome drinking water: - Organic matter should not exceed 1.5 grains per gallon; carbonate of lime, 16; sulphate of lime, 3; carbonate and sulphate of magnesia, 3; chloride of sodium should not exceed 10; carbonate of soda 20; sulphate of soda, 6; and of iron, 0.5; total, 60 grains.

The Bourne water has been analysed by Dr. Letheby, and this is his testimony: - grains per gallon, Organic matter, 0.26; carbonate of lime, 4.71; sulphate of lime, 1.73; carbonate of magnesia, 10.04; alkaline chloride, 10.62; alkaline nitrate, 0.70; silica, 0.50; grains, 28.33. We may judge, therefore, how free the water, which is the basis of Messrs. Mills's mineral waters, is free from all impurity - whether these be soda water, potash water, lemonade, seltzer water, lithia water, citrate potash, lithia and potash or carrara water.

So convinced are we of the excellence of these waters that we have no hesitation in reproducing the following description from a little pamphlet that was put into our

hands:

"Of various substances in water, there is none so absolutely deleterious as organic matter. The water obtained from the Artesian Well at Bourne, is, by the Analysis of Dr. Letheby, the purest in England, and different from the many well and river waters, which are generally more or less contaminated. The Bourne water is unequalled for its natural saline ingredients so well adapted to the manufacture of soda and other Aerated Waters, to which their acknowledged excellence is owing.

"From the analysis of the seventeen waters, by the British Medical Journal, we extract the following: 'Aerated Water from Bourne, Lincolnshire, Messrs.

R M Mills and Co.: total solids per gall., 119 grains; Alkalinity, 85 grains of neutral carbonate of soda per gall. of water. This is the equivalent to 8 grains of bicarbonate soda in each bottle of the Water. The Aerated Water from Bourne, made by Messrs. Mills, enjoys a high reputation, and is sold largely by some of the London Houses. This reputation it well

deserved as a pure Aerated Water. It contains a relatively large proportion of bicarbonate of soda, and it is evidently made from a very pure natural water. It is very palatable; and is much liked by those who enjoy Aerated Waters as a customary beverage.'

"Referring to the complete analysis of the Bourne Waters, made by Dr Letheby and other analytical chemists; it is nearly free from organic matter, only a quarter of a grain in 70,000 grains, or one gallon of water, while there is at the same time but a comparatively small amount of earthy salts dissolved from the strata through which it percolates, these being of the least hurtful tendency - the carbonate of magnesia predominating. Its purity contrasts favourably with every known water, not even excepting that of Loch Katrine, which contains 0.75 grains of organic matter."

Pleased with the visit we have paid to Bourne, we turn away from Messrs. Mill's manufactory into the streets. These are wide, and the houses are well built. The doors of the Bull Hotel stand invitingly open. There the wise Lord Burghleigh of Elizabeth's days was born; and, passing the threshold, whence he issued to guide England at a critical time, we find a substantial dinner for a moderate charge. Near the Bull are several notable buildings which show that there is true public spirit in the little town. There is a well-designed and carefully executed drinking fountain in an open space. It was erected in 1866 to the memory of John Lely Ostler, of Cawthorpe House.

Not far away is a new public building in one of the forms of Gothic, and which bears on its front the arms of the Exeter family, from whom the ground was obtained, and those of Hereward, "the last of the Saxons". Within this building there is a commodious public assembly-room, library and reading- room, and a billiard room - the place of meeting of the elite of the town.

Passing back to the railway station we come to Bourne Church. It is a massive edifice with some good features about it, though evidently standing in need of that restoration which it is now gradually undergoing. The interior of the church will at some day be exceedingly fine, if the restorations are carried out as judiciously as they have begun. The large columns which separate the nave from the aisles are Norman; but here and there are not wanting indications of Saxon work. Formerly

an Augustine Abbey stood here, but there are no traces of it remaining.

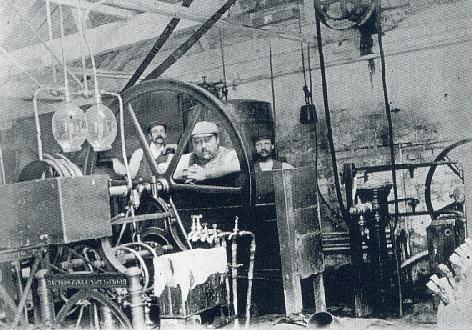

The

Red Hall, pictured circa 1870, when it was being used

as

the town's railway station

The vicarage stands on the old site; and it is a modern mansion, surrounded by extensive grounds. We cannot quit the railway station without adding a few words about it. The modern business of the railway is carried on in the ancient Red Hall

- an Elizabethan mansion of much interest, with an entrance of the Carolan period. The station master, Mr. Crossley, is evidently an enthusiast in gardening; and he does a work in which we wish that other station masters, or their assistants, would more universally partake. The ground between the hall and the line is a wilderness of delicious flowers; and there we saw a bed or violets that, when they are blown, must scent the air around. His rose culture is also noticeable. Upon one standard he has grafted several kinds of roses; and these are twined and intertwined with each other until they form a bower which will be beautiful indeed in the rose season.

At the other end of the station Mr. Crossley has another flower-bed just out of the shade of a spreading yew tree. He would bring additional benisons on his head, if he could have the ground under the tree covered with sward, and a seat placed about its trunk. In the hot weather, when passengers are waiting for the train, that would be a resting place much to be preferred to the ordinary waiting room.

See also Robert Mason Mills

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|