|

Saturday 5th January 2013

The restrictions on all night opening for the new filling station now being built in South Road have been lifted by South Kesteven District Council, a wise move not only in view of the economic climate but also because of the changing times in which we live. Bourne is no longer a sleepy backwater that the world has passed by but an expanding market town on a main road between London and the north and motorists passing through will expect the same services that they get elsewhere and to find them denied by bureaucratic meddling demeans our local authority. When planning permission was granted last year, councillors insisted that the filling station should close between 11.30 pm and 6 am on the grounds that people living nearby might be affected by undue light and noise but the owners asked them to think again and it has now been accepted that the location is some way from the nearest houses and so the restriction was lifted by the council’s development control committee at a meeting on Tuesday 18th December. The site will eventually include a petrol filling station, sandwich bar and Spar shop and there are still some concerns from members of the parish council at Thurlby because the site us actually within their parish but anyone who thinks it worthwhile to go down and take a look will realise that it is some distance away from the village and well out of earshot and so any inconvenience is highly unlikely. There remains, however, one curious anomaly in that the committee has insisted on banning deliveries to the service station at night and the operation of noisy equipment such as a car wash between 11.30 pm and 6 am even though it is located some distance further south from the Tesco supermarket which is quite close to houses on several sides yet is about to be allowed deliveries round the clock. Restrictions on lorries making deliveries at night and weekends were imposed when the superstore opened in February 2011 but the company applied to expand its hours last year after a survey of noise levels at nearby residential estates found them to be well within the acceptable guidelines even at night. The committee has now approved lifting the restrictions and so it can only be a matter of time before a similar decision is made about the service station further south on the A15. It is our opinion that local authorities should not concern themselves with such matters but do everything in their power to encourage new business moving in without imposing petty limitations. Opening hours, particularly, are a matter for the owners and they will be adjusted accordingly once they are up and running and if a problem with the neighbours emerges in the meantime, then that is the time they should intervene. My Christmas item on the Bourne Union or workhouse has produced an email from a reader who wanted to know more about the harsh conditions the inmates had to endure and wondered how they survived in such difficult times. Their lives were certainly regarded cheaply by those in power and there were many tragedies but one of the more moving incidents which occurred in the winter of 1858 illustrates what could happen and the attitude of the authorities. On Saturday 20th November that year, Ann Roslin, a girl of 20, left the workhouse only fourteen days after giving birth to a child. The stigma of birth out of wedlock was a heavy burden in those days and in most cases the man involved either disappeared or refused to accept responsibility while those who did had no money to provide for them. We have no record of the baby which most probably died at birth but the girl started walking the eight miles to Castle Bytham where it is believed that she had family and friends. When she reached Witham-on-the-Hill four miles away, she was too feeble to go any further and was obliged to stay all night and was given lodging by villagers who next morning took her by cart to Castle Bytham where she died a lingering death eight days later. “Is it not lamentable that a girl under such circumstances should be allowed to leave the union before a proper and decent time has elapsed?” asked the Stamford Mercury when reporting the girl’s death on December 3rd. The case aroused a great deal of public indignation and there was much criticism of the Board of Guardians and their governor who issued a statement trying to excuse their conduct by allowing a young woman leave their care so soon after giving birth. Their statement, subsequently published by the Grantham Journal on 11th December 1858, read: The newspaper’s comments relative to the unfortunate woman Roslin who quitted the Bourne Union so soon after her confinement are evidently intended to convey censures upon the Poor Law or its officers. It is not generally understood that the guardians and their officers are not empowered to detain even adult persons having any infectious disease and desirous to quit the workhouse, though by quitting it such persons may be likely to damage their own health or to endanger the health of others. All paupers leaving the workhouse under similar circumstances of this poor girl’s I invariably admonish for their impropriety and warn them of their danger. In this case I earnestly told her of the probable consequences in the presence of Thomas Hall, the Registrar, who also gave her the same advice as myself. There may be a little defect in the law in such cases but I am of the opinion if anyone is censurable it was her mother who, according to a previous arrangement, fetched her daughter from the workhouse twelve days after her confinement. Ironically, when the complaints were discussed at a special meeting on December 2nd, the guardians also considered the possibility of appointing a nurse to care for sick inmates, a suggestion which was turned down. Their report said: “In consequence of the sick list being so light, the guardians decided unanimously that a nurse was unnecessary as Mrs Holland, the matron, had always satisfactorily paid the required attention to the sick but in urgent cases where the matron was not in a position to provide, then the guardians will hire efficient persons temporarily.” The workhouse was built with room for 300 paupers although long stays were discouraged by the strict regime enforced and there is no record of a capacity ever being reached. Their report also enables us gauge the number of people living in the workhouse at that time because it states: “In the house at the commencement of the week 78, admitted 20, discharged two, remaining 96. Corresponding number last year 103, being seven less.” Despite the criticism of the poor standard of health care at the union, it was to be another twelve years before additional help was eventually sought to assist the sick and an advertisement which eventually appeared in the Stamford Mercury on Friday 3rd June 1870 under the heading “Bourne Union – Nurse wanted” gives an idea of the working conditions of the time: The Guardians of the Poor at the Bourne Union will, at their meeting to be held on the 16th day of June, proceed to the election of a nurse for the sick wards in the workhouse and to assist the matron in the general duties of the house. The salary will be £20 per annum with board, rations and washing. Candidates must be single women, between the ages of 30 and 45 years, and accustomed to nursing the sick, and must be able to read well. All information as to the duties etc can be obtained on application to the Master and Matron of the workhouse. Candidates are required to be in attendance at the boardroom on the day of election between eleven o’clock in the forenoon and to produce testimonials to their character and competency but no travelling expenses will be allowed. The person elected will be required to enter upon her duties on the 25th June instant. From the archives: Two hundred years ago, Robert Harrington, a poor lad, left Bourne to seek his fortune in London. He became a prosperous merchant and at his death, bequeathed his estate at Leytonstone to the deserving poor of Bourne. This yields an income of £1,800 from which has been distributed 66 pensions of £10 each, a number of small monetary doles, 200 tons of coal, 70 pairs of blankets, 500 yards of flannel and 1,500 yards of calico. The Charity Commissioners now wish to divert these funds for secondary education. – news item from the Nottingham Evening Post, Wednesday 3rd January 1900. Almost all of the inventions that have changed our landscape have been opposed in much the same way that wind turbines are now being attacked, one of the main criticisms being that they will deface the rural landscape. Electricity pylons or transmission towers that are used to carry overhead power cables across the countryside have been similarly condemned and yet as the years pass, these tall, steel, lattice towers will become an accepted part of our progress and even preserved for posterity once their usefulness has been replaced by even more modern techniques. Windmills have suffered the same fate especially in this part of South Lincolnshire where the skyline was once full of sails turning to drive water paddles which pushed water from the dykes into the drainage channels. Marshy fenland was drained in this way to produce crops and in the process, changing the fens into the richest farmland in Europe. These massive structures built to capture wind power were first used in Persia in the 7th century, making their appearance in England 500 years later, and have since been used for grinding grain, driving mechanical saws, raising coal and pumping water. When applied to land drainage they were sometimes known as wind pumps and were not always welcome. William Wheeler, in his history of the South Lincolnshire fens (1868), describes how in 1699, a landowner named Green erected one to drain his land and another was built in 1703 by Silas Tytus. Both were considered to be a nuisance and ordered to be pulled down. “These mills were opposed to popular opinion”, writes Wheeler, “although it was soon found impossible to resist the opportunity to use them.” An act to use mills for drainage of Haddenham Fen in Cambridgeshire became operative in 1726 and after that their use became general with windmills becoming a regular feature in the Deeping Fen from 1729 onwards. By 1763, fifty windmills are listed as working in Deeping Fen to drain some 30,000 acres of farmland. We know what they looked like because an 18th century watercolour painting of the scene survives (pictured above) together with a detailed description from Arthur Young during his survey of Lincolnshire in 1799: “The sails go 70 rounds and it raises 60 tons of water every minute, when in full work. Two men are necessary in winter, working night and day. It drains 1,900 acres.” The windmills were superseded by steam pumps in 1820, the first at Bottisham Fen, near Ely in Cambridgeshire, and at Deeping Fen four years later. As a result, one of these pumping mills was moved to Dyke village near Bourne around 1840 and converted for use as a corn mill and although it ceased to function after losing its sails around 1923, it remains a landmark today. Ironically, all of the windmills that now grace our landscape are listed to protect them for the future and it is a confident prediction that the same will eventually happen to electricity pylons, wind turbines and even solar farms, for these are the very essence of our industrial progress. Thought for the week: There's no way that solar panels or windmills can do it themselves. - Sir Patrick Moore (1923-2012), English amateur astronomer who achieved prominence in that field as a writer, researcher, radio commentator and television presenter. Saturday 12th January 2013

It has been apparent for many years that our health services are by no means safe and long term security for what we have is even more doubtful in the current economic climate. Hospitals have closed, patient facilities centralised and our ambulance service is under threat and even the Prime Minister, David Cameron, has warned that “there is still a long way to go” to raise standards of care in the National Health Service (BBC Online, January 4th) even though it was introduced 65 years ago. Local clinics are a particular necessity, especially for the old and chronically infirm and those situated in rural areas, and we can therefore imagine the dismay that has greeted the announcement that the village surgery at Rippingale, near Bourne, is to close in the spring. The decision has been taken by NHS Lincolnshire despite almost four years of opposition from the action group set up by villagers to fight the closure yet their protestations have fallen on stony ground. The surgery in Station Road will shut on March 31st and from then on patients will have to go to Billingborough almost five miles away to see a doctor. The parish council also mounted a spirited opposition against the closure, realising the hardship and inconvenience this will cause in the village, but to no avail and even though the decision has now been taken, they are not giving up. “We intend to take this to a higher level”, said chairman Mike Hallas. The council is particularly concerned about the poor newspaper coverage of their case and in a letter to the Stamford Mercury (January 11th) which carried the story last week, Mr Hallas claims that no mention was made of two patient consultations that were rejected and a refusal by the practice to allow access to documents relating to the closure while delays resulted in two other practices withdrawing their interest in taking over the surgery. “The decision appears to be more to do with administrative convenience than real patient care”, he writes. “But the story is not over, not least because New Springwells and the Primary Care Trust have to deliver a patient transport system in ten weeks.” In view of such scathing criticism, the welfare of villagers does not appear to have been given primary consideration, a sign of the changing relationship between doctor and patient over the years. Whereas it was once normal practice for doctors to visit the sick or to live within a convenient distance for the patient to visit them, the centralisation of services means that we must now go to them wherever they decide to be and home visits are discouraged. Rippingale has had its own doctor’s surgery for almost 180 years and currently has more than 1,000 registered patients. It began around 1841 at Down Hall, also known as the Doctor’s House, and then in 1968 moved to the village hall until a permanent clinic was built on the site of the old Methodist chapel, the premises being enlarged in 1997 when it was known as the Glenside Practice. The last full time doctor died in 2009 when it became clear that closure was on the cards and the service transferred to the New Springwells Practice at Billingborough which covers a large rural area from Sleaford to Bourne, west to Grantham and east to the edge of the fens. A recent survey at Rippingale revealed that more than 75% of villagers want to keep the surgery open and that there are real concerns about the availability of transport for patients to and from Billingborough. But NHS Lincolnshire say that the surgery building is no longer suitable and that the premises at Billingborough had been extended and improved during the past three years and could now accommodate the increased demands of the Rippingale branch but there would still be home visits to patients by doctors and practice nurses. The surgery closure will mark the end of an era for the village which also has a connection with Bourne because it was here that Dr John Galletly began his career as a family doctor more than a hundred years ago. He was born and educated in Scotland but came south in the late 19th century to practice in England, having done locum work in Cumberland where he met his wife Caroline. He moved to Rippingale in 1890 and lived at Down Hall at a time when emergencies relied on a farmer's cart to transport an injured patient while his district was limited to those places that could be reached by a pony and trap or even a bicycle. We know of the high regard in which Dr Galletly was held by villagers because an entry from the parish magazine of 1895 survives, telling us that he and his wife enjoyed singing and took part in concerts held in the schoolroom. “The doctor is about to move to Bourne”, said the entry. “During their stay amongst us, he and his wife have made many friends. The skill and attention he has shown in the treatment of all his patients have gained him universal esteem and confidence. In Mrs Galletly, we shall lose one who was ever ready to help in all church matters. She has been most helpful in the Sunday School and in the choir. We hear that Dr Galletly is not giving up the Rippingale practice but intends to put an assistant here so we shall not be losing him altogether, for which we are glad.” Dr Galletly eventually moved to Bourne to take over Dr Robert Brown’s practice in North Road, a property that once stood near the present bus station, later building a new house at No 40 North Road where the surgery remained for the next 70 years and is today the home of the Galletly Practice. His son, also John, was sent to London to study medicine, returning to help his father and taking over completely when he died in 1937, thus continuing a lifelong love of Bourne and its people and becoming one of the town’s best known family doctors. But what, I wonder, would he have to say about the closure of the village surgery at Rippingale where his father had begun his career in practice? The life of a family doctor has changed dramatically since those days and apart from extremely high salaries, general practitioners also enjoy a five day week, even though ill health does not keep office hours. If patients need urgent medical help at weekends it is left to the paramedics and emergency services to cope. The current routine of the family doctor sitting behind his computer screen and seeing one patient every ten minutes while ticking boxes and printing out prescriptions from Monday to Friday, nine to five, is a sharp contrast to what it was in past times. When Dr Galletly returned to Bourne in 1927, he swapped the routine of hospital work in the metropolis for a daily round of births and deaths, fractures and bruises, extracting teeth and tonsils, dealing with diseases and infections and even mixing his own medicines. At one time, he delivered more than 50 babies a year, went to road accidents, performed operations on the kitchen table, attended the Butterfield Hospital for consultations and saw patients at his surgery twice a day yet was always on call and still found time for an active public life with many organisations including Bourne Urban District Council of which he became chairman. His night calls were many, often hazardous expeditions that involved walking or cycling to outlying villages in bad weather to attend emergencies, sometimes even losing his way in the dark, until guided by the welcome light of an oil lamp in the window. It would be unrealistic to expect the hours that Dr Galletly worked to be emulated today but even twenty years ago he criticised the sweeping changes in general practice that were resulting in doctors working fewer hours for more pay because people’s fears in time of illness remain unchanged. The present arrangements may be regarded as more efficient than they were in those days but the bedside manner has gone and with it the confidence that a patient once enjoyed with their doctor. In his retirement years, Dr Galletly admitted that he missed what he called, the old days and compared them with the role of the doctor in today's modern practices. Shortly before his death in 1993 at the age of 94, he remembered that personal touch that is now missing when he wrote: "The burden of the general practitioner has been lightened very much but is he now as much a member of the community as he used to be? Does he still have to wonder what is meant by 'the vapours' or dissuade a patient from the use of bread as a poultice or even goose grease? And will he find a nice cup of tea and a piece of cake for him after attending a confinement?" From the archives: A wealthy tramp - sojourn in Lincoln Gaol at his own expense: Alfred Condeenay, who described himself as “a musician on the pan pipes” and giving his address in Scotland, was charged with begging at Morton, near Bourne. Police saw him calling at several houses asking for money and on being arrested, the prisoner confessed that he had been “cadging”. “You’re right”, he told Constable Wilkinson. “You’ve copped me fair. But what will you take to let me free” and then offered the constable half a sovereign if he would release him. When searched at the police station, a large amount of money was found secreted in various parts of his tattered clothes, ten guineas in gold and silver was securely sewed in the lining of his waistcoat and £1 3s. 4½d. concealed in the lining of his trousers. He was committed to prison for 14 days and ordered to pay for his conveyance to Lincoln and for his maintenance. – news item from the Lincolnshire Echo, Friday 21st April 1893. Our village churches are a frequent target for thieves particularly those in isolated locations such as that at Kirkby Underwood, five miles north of Bourne, where it stands some distance away from the village and as a result lead has been taken from the roof on several occasions. One of the worst thefts occurred in July 2011 when night time intruders stripped 36 square metres from the roof of the south and north nave causing damage estimated at £20,000. This was a major blow for the church and a temporary roof was installed immediately to protect the building from the weather while a fund was launched to pay for permanent repairs, including a novel sponsorship scheme which sought donations to finance each square foot of replacement and attracted gifts from New Zealand, Australia and the United States. The new roof made from a special coated stainless steel was completed in 2012 and last month a dedication service was held by the Bishop of Lincoln, the Rt Rev Christopher Lowson, who made special mention of the generosity of those who had contributed and the unusual sponsorship scheme which had made a considerable reduction in the financial burden on the parochial church council. The culprits have been brought to justice and on 13th December 2012, five men were jailed at Lincoln Crown Court for the theft of the lead at Kirkby Underwood and 19 other churches across the East Midlands. The court was told that they were members of a gang of six Lithuanian nationals who had caused £1 million worth of damage and it is estimated that they stole 70 tonnes of lead which they sold for £70,000. Passing sentence, Judge Michael Heath, told them: "These thefts caused serious financial consequences and we should not underestimate the distress felt by Christians at the desecration of their sacred places of divine worship." The five men were given jail sentences varying from six months to seven years, a total of 20 years. England's ancient churches are an essential part of our heritage, monuments not only of religious faith but also of our spirit of community but they do need hard work to keep them in good order and to prevent deterioration, whether by wind and weather or theft and vandalism. Faith is not enough and it is a constant struggle to find money and volunteers to do the work and the way in which villagers at Kirkby Underwood have rallied to remedy their own unwanted setback has been quite remarkable. Thought for the week: Everyone who has a heart, however ignorant of architecture he may be, feels the transcendent beauty and poetry of the mediaeval churches. - Goldwin Smith (1823-1910), British historian, journalist and Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford, who threw his energy into the cause of university reform. Saturday 19th January 2013

The cost of establishing the new Community Access Point at the Corn Exchange in Bourne has rocketed threefold in a mere twelve months, according to figures published in a front page report by The Local newspaper (January 11th). The original estimate given when planning permission was granted by South Kesteven District Council in January 2012 was £200,000, although this had risen to £263,480 when the contract was awarded in March, but the figure has now soared to £600,000 which hardly seems an appropriate expenditure at a time of economic crisis and as the authority will soon be considering the budget for the coming financial year, perhaps we will be given an explanation as to why there has been such a massive increase in such short a time. The newspaper also states that the work is now in the final stages and the project will be officially opened on Wednesday 6th March. The report adds: “About 40 staff from South Kesteven District Council, most of whom, are currently based in Grantham, and Bourne Town Council, will move into offices created on the first floor next month as the development is running ahead of schedule.” It will be a matter of speculation over whether there is enough work in Bourne for such a large number of white collar workers from the district council or perhaps there so many of them at the Grantham headquarters that there is no more room. More importantly, it does seem such a small space to pack that many office staff into a building that will also be housing a department from Lincolnshire County Council, the offices of Bourne Town Council, the register office, a customer services counter, interview rooms, the Citizens' Advice Bureau, kitchen, coffee room and changing rooms, and, not least, our public library with a reference section, a bank of computers with internet access points, and a children’s reading room which are all scheduled to move from their current premises in South Street. This column has already predicted that the scheme will be like trying to put a quart into a pint pot but the indications are that even the pot is not as big as we first thought, despite the phenomenal rise in cost. Apart from the staffing problem, there are already signs that the public library will be downgraded and although employees have not yet been allowed to take a look at progress on their new premises, the evidence is that there will be less space with fewer facilities. A visit to the South Street library last week revealed that the popular and well-used reference section which once covered an entire wall, bookshelves crammed with volumes on this subject and that, has all but disappeared in readiness for the move while the area of tables and chairs reserved for reading and study is also being phased out. Worse still is the question of car parking which by all accounts is sure to be at a premium. The present premises in South Street have nine spaces which are always busy but there will be none allocated for library users outside the Corn Exchange where there is already insufficient space yet to this impossible scenario will be added the cars of 40 or more council workers, plus those from the library staff and all of those other people who want to use the services housed here, and imagine the chaos that will ensue on Thursdays when the entire area is taken up with market stalls and shoppers. Perhaps council workers will be given special passes to use the adjoining car park at the Co-operative Food supermarket where waiting time is limited to two hours. If so, this means that they will occupy spaces at the expense of town centre shoppers who regularly park there and if they are repeatedly stuck for a space then they will go elsewhere, much to the detriment of our local traders who are already having a difficult time. From the archives: The move will mean longer opening hours, better parking and a newly-refurbished home, making it easier to visit at a time that’s convenient to you. – report from County News (Summer 2012), the free magazine issued by Lincolnshire County Council, singing the praises of relocating the public library from South Street to the Corn Exchange. The custom of installing blue plaques on buildings associated with the great and the good throughout the country is to end for the time being because English Heritage can no longer afford to pay for them following a cut in government funding. The first was erected in 1867 when Lord Byron was honoured with a plaque on his former London home and since English Heritage took responsibility for the scheme in 1986, more than 350 have appeared, usually on the recommendation of the public, the stipulation being that candidates must have been dead for 20 years or have passed the centenary of their birth and must be generally regarded as eminent. Those that we have are to remain in situ but English Heritage will not be considering any new nominations and the scheme is being suspended for the time being. This is a pity because these distinctive plaques are a reminder of famous people who have made their mark in life and are therefore a tremendous boost for tourism. There is only one in Bourne and because of the decision by English Heritage we are unlikely to get any more. It was erected on the front of Wake House in North Street in December 2002 to commemorate the life of Charles Worth (1825-95), the solicitor’s son who was born there and went on to achieve fame in Paris as an international fashion designer and founder of haute couture. The blue plaque replaced a more modest one erected by the former Bourne Urban District Council many years before but it has been preserved and now hangs in the entrance foyer of Wake House which is used for various community activities. The decision by English Heritage, however, should not stop local authorities and other organisations from financing their own blue plaques. Bourne Town Council has already shown the way by erecting one in June 2009 on the front of the Burghley Arms in the town centre to commemorate Frederic Manning (1882-1935), the Australian poet and author who lived there for a time while writing his famous novel about life in the trenches during the Great War, The Middle Parts of Fortune, later entitled Her Privates We. The date on the front actually says 2007 but there was a delay while attempts were made to persuade someone from the Australian High Commission in London to unveil it, but they were unsuccessful. The circular plaque cost £400 and was financed from council funds, a tasteful work in blue with gilt lettering and a reminder to those who pass by of the man who laboured within to produce such a notable literary work. There is already another plaque on the Burghley Arms, erected by BUDC soon after the name of the inn was changed in 1955, informing us that this was the birthplace of the illustrious Elizabethan statesman, William Cecil (1520-98), trusted adviser to Queen Elizabeth I and the first Lord Burghley, when it was a private house owned by his parents, Richard and Jane Cecil. The building became a coaching inn around 1717 when it was called the Bull and Swan although by the 19th century it was known simply as the Bull. There have been suggestions that Raymond Mays (1899-1980), the inspiration behind the BRM, should have been given a blue plaque for his contribution to international motor racing but this never materialised although he is remembered by an oval iron sign that was erected on the outside wall of his lifetime home at Eastgate House soon after his death. Unfortunately, it became a target for vandals in 2007 when it was daubed with spray paint but was later restored to its original condition by the Civic Society. Many more of our leading citizens are remembered among the 250 street names around Bourne and they include the great and the good who have made their mark such as councillors, doctors, nurses and businessmen. There is also another similar memorial which remembers the ordinary people of this town and their stoicism and fortitude in the face of austerity and uncertainty during the Second World War of 1939-45. Sixty years after the conflict ended, the town council erected a blue plaque on the front of the Town Hall in 2006 to acknowledge their contribution to the national effort both in the armed forces and on the home front. All of these memorial plaques are an essential part of our heritage because they serve as a daily reminder for future generations of those people and events which had a momentous effect on our community in past times but could easily be forgotten with the passage of time. It is a pity that English Heritage is dropping the scheme but it is hoped that this could be the signal for others to ensure that it continues. Hindsight is a wonderful thing and were those who run our affairs to possess it, many of the failures that affect our future would not have occurred. Bourne has had its share but the closure of our watercress industry must rank high on the list of enterprises that would be thriving today had those in charge during its final years been able to see into the future. A century ago, watercress was produced here in abundance because the town had an ample supply of the right commodity for its cultivation, namely a continual supply of pure water. The business thrived for eighty years but despite this sustained prosperity, later owners allowed it to decline to the point where it was no longer economical and so it passed into history and the few plants that continue to appear each year along the course of the Bourne Eau in South Street where the watercress beds were situated are the only remains of a once prosperous undertaking. Watercress was a popular plant that was used long ago by the general Xenophon in ancient Greece as a tonic for his soldiers and in later centuries the growing of this excellent salad crop was a preoccupation at many places in England where there was an abundant supply of flowing water that was necessary for its production and Bourne, with its natural springs rising at the Wellhead, was the perfect place. The watercress industry was established by Edwin Nathaniel Moody in 1896 on land adjoining St Peter’s Pool and production soon became so prolific and the demand so great that further plantations were established at the rear of Harrington Street, land that is now Baldwin Grove, and at Kate’s Bridge on the main A15 south of the town. The cress beds were eventually taken over by Spalding Urban District Council in 1955 who kept them going until 1969 when they were bought by the South Lincolnshire Water Board who continued to run them until April 1974 when they were closed down and filled in and so an important industry was lost to the town. This is a pity because watercress is now enjoying a new reputation as one of the healthiest foods you can possibly eat, rich in vitamins and other nutrients, and would therefore be a welcome addition to our diet if the locally grown product were immediately available, bunched and freshly picked, rather than the packaged variety from the supermarkets which, we are told, is less beneficial. The latest craze is for the ladies to eat it as a beauty super food after a scientific study revealed that the peppery leaves can drastically reduce wrinkles and increase energy levels because it contains more vitamin C than oranges and more iron than spinach. “It is a powerhouse of nutrients that work together to maintain a good skin”, said Dr Sarah Schenker who supervised the study (Daily Mail, 22nd November 2012). What a business we have lost. In 1911, practically the entire output from Bourne was being sent to wholesale markets in London, the Midlands and elsewhere in the country and at the height of the cutting season, around 70 hampers were being despatched by train each week, that is by weight, 500 stones or three tons, quite a remarkable achievement for a little known industry in a small South Lincolnshire market town. Thought for the week: The wisdom of hindsight, so useful to historians and indeed to authors of memoirs, is sadly denied to practicing politicians. - Margaret Thatcher (1925- ), the only woman Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, who served from 1979 to 1990 and who became known as "the Iron Lady". Saturday 26th January 2013

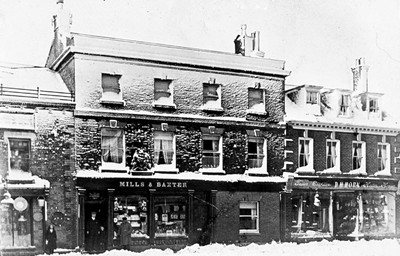

There is something inevitable about snow because the moment it falls the nation goes into bottom gear. Roads become impassable, schools close, trains are late, airports are at a standstill and workers see it as an excuse not to clock on. But children enjoy it because it may mean a day off lessons and they can be seen snowballing and sledging, building snowmen and generally revelling in the wintry weather. The mantle of white that falls overnight turns the countryside into a winter wonderland and we wake to find the trees and shrubs frozen in time and glistening with snowflakes that cling to the branches, a beautiful scene that belies the chaos it causes and although many enjoy this marvellous sight, reality soon sets in and we wait impatiently for it to disappear and for our world to return to normal. Snowfalls of any severity are usually short lived and so those that persisted have found a place in the record books, among them the blizzard that occurred in Bourne during the General Election of 1910, a straight fight between the Conservative candidate, Major Claud Willoughby, son of the first Earl of Ancaster, of Grimsthorpe Castle, and the Liberal candidate, Mr G H Parkin. Polling day was fixed for Friday 28th January and the Corn Exchange chosen for the count the following day and although it was expected to be a straightforward campaign, the candidates had reckoned without the weather. During the night, there had been a heavy snowfall which had settled to a depth of several inches in many places, Bourne being particularly affected, while the forecast was not good and the day dawned with yet more snow, thus hampering voters from outlying districts in reaching the polling booths. The continued severe weather was also a bad omen as cars were being used for the first time in a local election to take people in to cast their votes added to which Bourne at that time was part of a very large constituency containing over 150 parishes and extending from Beckingham in the north to Crowland in the south, a distance of almost 60 miles by road and 27 miles from east to west. The snow was therefore a major setback for the candidates, Major Willoughby for instance having more than 100 vehicles at his disposal which had been loaned by friends and relatives, and the effect was soon evident when they started skidding and sliding on the icy roads and then began breaking down and as they were either towed away or abandoned, some electors experienced the novelty of being taken to the polls on a sledge. The only incident of an unpleasant nature occurred at Stamford where Mr Parkin was struck in the face by a snowball and received a slight injury. The weather was still bad the following day when the candidates assembled for the count at the Corn Exchange where Major Willoughby was elected by a majority of 356 votes. He received a tumultuous reception when he addressed the waiting crowd but there was another heavy snowfall as he began a triumphal tour of the town with a motorcade of 20 vehicles, he and his wife Lady Florence in the first car which eventually broke down because of the freezing temperatures but supporters refused to be beaten and so they hitched ropes to the axles and pulled him for the rest of the way. Another exceptional occasion for snow in Bourne was a blizzard in 1916 which caused major disruption to public services and left a trail of damage across the district. The wintry conditions prevailed throughout Tuesday 28th March when trees were uprooted in various parts of the town, four on the Abbey Lawn, three in Mill Drove, two near the villas in West Road, three in a field near the railway station at the Red Hall, two at the bottom of Eastgate and one close to Dr John Gilpin's surgery at Brook Lodge in South Street. The telephone and telegraph services were cut off and on Tuesday evening it was reported that not a single telephone subscriber could be reached while the following morning telegrams were not being accepted by the Post Office because they were unable to send them. One telegram sent before noon on the Tuesday was not delivered until 9 o'clock the following morning, an unheard of delay. Rail services were badly disrupted and trains due into Bourne from Saxby just before 11 am on Tuesday were held up by deep snow drifts at South Witham and had still not arrived by midday the following day. The 12.15 pm express to Leicester reached South Witham but was forced to return with its passengers to Norwich. All trains were running late on the Great Northern system and the journey to Grantham took about four hours. A train which left Bourne for Spalding at 3 pm to bring home passengers from Spalding market arrived in Bourne at 7 pm in the evening after the electric signalling system at Twenty failed. The motor mail cart bringing in the morning mail from Peterborough which was usually due at Bourne at 4 am did not arrive until after 7 am on both Tuesday and Wednesday and on the Tuesday run it was held up by telegraph poles that had blown down across the road. The Great War of 1914-18 was in progress and among the passengers stranded at Bourne railway station were three soldiers who were given beds for the night at the Vestry Hall which had been converted for use as a Red Cross hospital for convalescent servicemen. The surprising feature of the storm was that it caused only a small amount of structural damage to property, mainly dislodging slates, tiles and guttering that collapsed under the weight of snow but the town was virtually isolated for several days. Serious snowfalls in recent years have been relatively few although the life of the town was badly disrupted in 1920 and again in 1947 and 1963 while a fall in 1987 saw tractors clearing the town centre. The documentary evidence seems to indicate, however, that people in the past made a more concerted effort to continue with their daily round rather than succumb and take a day off but then it must be remembered that paid leave of absence for whatever reason was virtually unknown until recent times. From the archives: ACCIDENTS: On Sunday afternoon last, Mrs Elfleet, senior, aged eighty-two, fell upon the causeway in Star-lane [now Abbey Road] and broke a thigh. The slippery state of the roads and paths during the last few days has caused a great number of accidents from falls. The very reprehensible practice of boys sliding upon the causeways is too prevalent in Bourne and ought to be put a stop to in some way or other. - news item from the Grantham Journal, Saturday 1st January 1870. Colonel Bill Bell has died at the age of 100 after a distinguished career in the army during the Second World War of 1939-45 when he was awarded an MC in Tunisia in 1943 and a DSO in Italy the following year. He also has a connection with Bourne in that this was originally his home town where his ancestors had become pillars of the community during two centuries. Although known as Colonel Bill Bell, he was born Francis Cecil Leonard Bell in September 1912, son of Cecil Walker Bell (1868-1947), a well-known solicitor who lived at the family home in West Street that survives today as Bourne House, now converted into retirement apartments. His father was a member of an old established family of lawyers which practised in Bourne for 150 years, holding many public appointments in the town including coroner, clerk to Bourne Urban District Council and South Kesteven District Council, registrar of the county court and was one of the first governors of Bourne Grammar School. He also had a military background himself, a part-time soldier who was proud of his army commission, commanding H Company, the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, the Lincolnshire Regiment, for 11 years and rising to the rank of major. Francis was educated at Gresham’s School where he excelled at sport, especially hockey, which he later played for Lincolnshire. He also studied law and qualified as a solicitor before moving to London in 1937 to join the Board of Trade’s legal department, working there until the outbreak of war. He had been commissioned into the 4th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment (TA) in 1931 and transferred to 6 LR in 1939, accompanying this unit to France as part of the BEF and was evacuated from Dunkirk in a flat-bottomed Chinese river gunboat. He was mentioned in despatches. In July 1944, Bell took command of the 6th Battalion the Lincolnshire Regiment (6 LR) in Italy and the citation for the award of his DSO said: “Colonel Bell has served in this battalion in all ranks from platoon commander to commanding officer. His conduct and gallantry throughout the war and his inspiring leadership in action have been outstanding. By his personal leadership in the thick of battle he has often turned difficult situations into major successes.” In January 1943, he landed in Algiers and two months later, as a company commander of 6 LR at Sedjenane, Tunisia, he was awarded an MC for repelling a series of determined attacks and for frustrating an outflanking movement. The citation also stated that, in the face of relentless sniping, he had attempted to rescue a wounded officer who was lying in the open. The officer died as Bell reached him. He later served in the North African campaign, during the landings at Salerno in September 1943 and in fierce fighting at Monte Cassino in the winter of 1943-44. He also accompanied 6 LR when it moved to Greece and then on its return to Italy in the final month of the campaign. After the war, Bell returned to the Board of Trade and later became chief legal adviser to Lloyds Bank, retiring in 1977 and for the next five years, was director of the British Bankers’ Association (then known as the Committee of London Clearing Banks) and chairman of its European Legal Committee. He attended regimental reunions in Lincolnshire until he was in his late eighties and served as trustee and president of the Battalion Benevolent Fund and in 1967 he was appointed Honorary Colonel of the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment (Territorial). In retirement and settled at Chiddingfold, Surrey, Bell was able to indulge his enthusiasm for fishing and shooting. A man of considerable charm, he was excellent company and loved good food and wine. At his 100th birthday party he enjoyed several glasses of vintage Pol Roger. Colonel Bell died on 20th December 2012. He had married first in 1942 to Mary Wynne Jacob who predeceased him and secondly in 1999 to Priscilla Muir who survives him with a son and daughter of his first marriage. Ironically, Bourne might have remained Colonel Bell's home town had not his father moved to the south coast in 1940 following an acrimonious disagreement a few years earlier when he was a lay preacher and people's warden at the Abbey Church where he also sang in the choir for 40 years. The dispute led to a prolonged libel hearing at Lincolnshire Assizes in June 1933 in which he was sued for damages by the Vicar of Bourne, Canon John Grinter, who claimed that his reputation had been impugned when it was alleged that a gift of £100 given to him by a parishioner for the church’s repair fund had in fact been kept for his own use. Major Bell offered to make amends by publishing an apology in the newspapers but this was refused by the vicar who believed that his reputation was at stake. After a three day hearing the jury found in the vicar's favour but awarded him a mere £5 in damages with costs in a case which the judge, Mr Justice Finlay, described as "discreditable and squalid" and one that should never have been brought before the court. He said that the damages could not be regarded as contemptuous though they were not generous. “I have disliked trying this as much as any case I remember”, he said. “The parties have a perfect right to come here for a verdict at your hands but it is a most unhappy thing that this action should ever have been fought.” Canon Grinter, who had been vicar since 1919, tendered his resignation to the Bishop of Lincoln and left Bourne in November 1935. Cecil Bell never returned to Bourne and died at Eastbourne in 1947, aged 78. Thought for the week: Libel actions, when we look at them in perspective, are an ornament of a civilized society. They have replaced, after all, at least in most cases, a resort to weapons in defence of a reputation. - Henry Anatole Grunwald (1922-2005), Austrian-born journalist and diplomat who became managing editor of TIME magazine and in 2001, he was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class. Return to Monthly entries |