|

Saturday 1st December 2012

The mood of the public meeting held at the Corn Exchange in Bourne on Monday said it all. Hands off our ambulance service. This was part of the official consultation procedure and it is therefore expected that the opposition to the proposed changes will be taken on board by the East Midlands Ambulance Service (EMAS) but we cannot count on it.

Almost 100 people

attended the protest meeting at Bourne which was requested by the mayor,

Councillor Helen Powell, after the town had been left out of the scheduled

consultation venues although Phil Milligan, chief executive of EMAS, failed to

appear and the director of finance and performance, Jon Sargeant, answered

questions instead. He faced an audience that included town councillor Brenda

Johnson (Bourne East) who had set up an action group to fight the proposals with

a band of supporters all wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the motto “Save our

ambulance stations” and there was particular concern about a reduction in the

ambulance service at a time when Bourne’s population was expanding rapidly

because of major housing projects such as Elsea Park. Everyone who attended

the meeting and those who did not are being urged to sign a petition now being

circulated in the town to keep the ambulance station open and to give their

feedback on the proposals before the public consultation ends on December 17th. The Red Hall

is

now being hired out for weddings and other events and the venue is being

advertised in an attempt to secure bookings. A leaflet has been produced by

Bourne United Charities which administers the building and the terms and

conditions detailed on its web site. The Grade II listed mansion dates back to

the early 17th century and the magnificent frontage will provide a most

picturesque setting for the bride and groom when their wedding photographs are

taken. Certainly the house has

been largely empty for the past thirty years and only being used as the office

and boardroom of Bourne United Charities with occasional events held by local

clubs in the reception room, and by making the facilities available to a wider

range of people and organisations it should produce additional income although

not everyone will be welcome. There is a ban, for instance, on 18th and 21st

birthday celebrations or indeed any parties for young people although the

conditions of hire do not stipulate whether this includes christenings, and the

number of guests will be restricted to 100 at all times. The Red Hall has had a

chequered history since it was built in 1605 as the country home of a wealthy

London grocer. It has since been used as a boarding school and for almost a

century as the booking office for the town’s railway station during which time

it withstood the vibrations of countless steam locomotives and rolling stock

rumbling past before being acquired by Bourne United Charities for community use

in 1962. The restoration work

carried out over the next ten years with the aid of grants and donations ensured

the future of the building and the latest venture will enable guests see the

interior during their chosen event at the rate of £100 a day. This would

therefore seem to be an appropriate time for the trustees to give the town the

opportunity to take a look at the inside of our most famous secular building

free of charge on selected open days such as those held elsewhere in England at

similar historic buildings in which the public has a vested interest. The question that

perpetually haunts historians is whether the past exists if it has not been

recorded and whether the events which we know about are deemed to be history

merely because someone wrote them down at the time. Unless we know that something actually happened, there can only be speculation about past occurrences and this raises the second important question about the reliability of old documents, particularly the chronicles of past times before the advent of the printing press and the computer. These accounts were written by hand, usually many years, even centuries, after the event and often by people who were not there and therefore relied on stories that had been passed down through what has become known as the oral tradition, each embellished and exaggerated with the re-telling.

They are therefore suspect and cannot be relied upon as a truthful account of the subject in hand. Yet some historians regard these old documents as sacrosanct and use them as a major source for their research, accepting them at their face value despite the anomalies thrown up by later investigation while the copying of earlier works is a regular occurrence and so mistakes once made are repeated down the ages to the present day. Because of its size, Bourne has fewer documentary references than most but the majority from later centuries bear a marked similarity to each other and identical errors abound.

Saturday 8th December 2012

The town’s latest public house opened in South Road on Monday and is setting a high standard for service and quality that is sure to attract trade from our established hostelries. The facilities at the Sugar Mill are extensive, the atmosphere both intimate and inviting, the food and drink of the highest quality and the prices reasonable. Plenty of staff are on hand to ensure that there is no waiting and there is ample car parking space outside and so this new outlet excels on all counts. I mention these matters because the public house where we have been going for a weekly lunchtime drink for the past ten years has been slowly declining in standard with up to half an hour to serve our order on some occasions and in recent weeks the heating has been switched off in the bar which meant that on really cold days we oldies have gone home after an hour or so feeling as though hypothermia had set in. We therefore went to the Sugar Mill which is a far more comfortable place and I feel that many others will follow suit and so our existing public houses will have to ensure that they match the new standard that has been set or suffer the effects of competition, which is as it should be in a free society. By all means we should support the outlets we have but at the same time it is up to the owners not to treat their customers with disdain. There is no doubt that the new pub is a welcome addition to our facilities and the forecast by Councillor Linda Neal, leader of South Kesteven District Council, is already coming true because she told The Local newspaper (July 27th): "This is good news for the town. The pub will be an important asset to Bourne and unlike any other facilities we currently have." The opening of the Sugar Mill certainly goes against current trend of closures with the Crown in West Street shutting in 1991 followed by the Royal Oak in North Street in 2009 and the Marquess of Granby in Abbey Road two years later. The newest addition means that there are now twelve public houses in Bourne which is about the average over the past 100 years. Other closures mean that Bourne has lost some very popular names that will be quite unfamiliar to residents today such as the Boat Inn in South Fen, the Elephant and Castle in North Street, the Butcher’s Arms, the Old Wharf Inn and the Woolpack in Eastgate, the Horse and Groom in West Street, the Light Dragoon in Abbey Road, the New Inn in Victoria Place, the Railway Tavern in the Austerby, the Six Bells in North Street, the Three Horseshoes in North Fen, the Six Bells, Waggon and Horses and the Old Windmill Inn in North Street, all now long gone. It is therefore obvious that the town has never been short of hostelries and in 1857 there were eleven taverns or public houses and fourteen by the end of the century. Since then, there has been a fluctuating pattern of closures and openings with the most dramatic developments occurring during the final years of the 20th century when the face of the traditional public house began to change, influenced by varying ownership, an increase in opening hours, the ban on smoking in public places, a decline in drinking habits and a demand for food to be served which is now an essential part of the service. Among those that have survived are the Golden Lion in West Street and the Red Lion in South Street, a favourite haunt of young people, especially at weekends, while across the road is the stone built Mason's Arms. There is also the Nag's Head in the town centre and the exterior of this building is largely unchanged since it was erected during the early 19th century in the yellow brick and blue slate much favoured by Victorian builders. This hostelry appears to have assumed the name the Nag's Head Hotel that had been discarded by the Angel around 1800 although this has been shortened in recent years to just the Nag's Head, a name that reflects the Englishman's affection for the horse in this agricultural community although it has been interpreted in some districts as a shrewish wife. One of the most recent of our public houses was opened in May 2002 in a converted shop on the west side of North Street. A grocery business founded by John Smith in 1857 operated from this three-storey Grade II listed building until it closed in December 1998. Planning permission was subsequently granted for it to be turned into a public house but the new owners have incorporated several of the original features in the refurbished premises, including the Victorian window and the old enamelled trade plates on the front, and they have also retained the original business name, Smiths of Bourne, by which the new public house is now known. Other newcomers to the scene are the Jubilee Garage, opened across the road at No 30 North Street in 2006 in a building with a chequered history as an ironmonger’s shop, garage and blacksmith’s forge but retaining features from all three, and Firkin Ale, also established in former retail premises nearby at No 36 North Street, and all have already become popular haunts. Not all of our pubs, however, are doing good business as recent changes in managership have shown with some vacancies unfilled for several months and so any new challenge to current trade may be good news for customers but it will not please all of our licensees. From the archives (1): An inquest at the Nag's Head Inn before Mr William Edwards, coroner, on Monday 3rd September, on the body of Mr John Morris, aged 46, a wheelwright, of West Street, Bourne, was told that he was in his usual health on Saturday evening and at the Windmill Inn in North Street [now demolished], partook of some glasses of spirits after which, at about half past 10, he went to the Nag's Head where he drank more liquors, and at 11 o'clock, he fell out of his chair. Mr Octavius Munton, surgeon, who was sent for, promptly attended and attempted to bleed deceased but life was extinct. Verdict: apoplexy which it appeared from the medical testimony, the unfortunate man was liable to from any exciting cause. - news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 7th September 1855. From the archives (2): An inquest was told on Monday that Thomas Smith, a labourer, of Eastgate, Bourne, died suddenly in the Woolpack Inn at Eastgate [now demolished] at the weekend. It appears that he went into the inn on Saturday afternoon and called for half a pint of beer. The landlord went out of the room to execute the order and on returning, found Smith on the floor dead. The jury, after hearing the evidence, returned a verdict of death from natural causes. – news report from the Stamford Mercury, Friday 9th October 1885. The power of prayer has been the subject of debate for centuries and it has never been proven either way whether it is effective or not other than providing a spiritual placebo for those who believe. There is nothing wrong with this for which unbeliever has not, like many a biblical character in early times, promised eternal allegiance provided a pressing problem were solved or a burden relieved. It was therefore heartening to read in Stamford Mercury that gritting lorries and their drivers which are already on standby for the forthcoming winter have been blessed by various members of the clergy including the Bishop of Lincoln, the Rt Rev Christopher Lowson, during special ceremonies at county council highways depots around the county including our own at Thurlby, near Bourne (November 30th). We are told that a fleet of 43 gritting lorries are ready for action onf all of Lincolnshire’s A and B roads if needed and this annual religious ritual symbolises the spreading of the gospel as the mixture of salt and sand is scattered over them in extreme weather conditions when motorists are advised not to travel unless absolutely necessary. This is a most worthy event because it not only raises the profile of the gritting fleet but also provides an assurance that our roads will be kept safe and driveable whatever the weather. It may, however, be tempting fate, because in the event of a gritting lorry being involved in an accident then God is likely to get the blame. There is also the factor of unforeseen circumstances that even the Almighty cannot seem to predict. In December 2008 for instance, the same morning that a newspaper report appeared about the blessing ceremony, conditions were freezing with unexpected black ice covering many roads and by 8.30 am one driver had complained that when he drove into town the surfaces were treacherous and untreated with not a gritting lorry in sight. This has been the case on many occasions in past years and so perhaps the order of service should be changed in the future to include prayers for a more efficient early warning system and all motorists, believers or not, would say amen to that. Shoppers at Sainsbury’s supermarket in Exeter Street were entertained on Saturday morning by a silver band from the Salvation Army playing carols, even though it was only December 1st. Despite this early reminder of the festive season it was all quite enjoyable and we found ourselves singing along in the aisles with many other customers, encouraged not so much by the Christmas music but by the enthusiasm of the players. One customer remarked that the Sally Anne was always quick off the mark on such occasions and so they were probably the first in Bourne with their carols and collecting box before the inevitable seasonal fatigue sets in because in a week or so we will be besieged by appeals for good causes and our Christmas goodwill stretched to the limit. There is something very evocative about a military band especially one from the Sally Anne which is regarded with some affection by old soldiers such as myself who remember their dedication by running canteens at isolated army camps and always turning up with very welcome tea and buns at remote exercise locations in the most extreme of weather and always ready to serve us with a smile and so whenever I hear them play, I have to contribute. This evangelical Christian movement originated in the mid-19th century and now has an international presence with representatives in many countries around the world. The prime mover was William Booth (1829-1912) who founded the social service and social reform organisation in London in 1865 under the name of the Christian Revival Association. Five years later it was renamed the East London Christian Mission but from 1878 it has been known as the Salvation Army. The leaders have military titles and the movement is renowned for its distinctive blue and red uniforms, brass bands and a weekly journal called the War Cry that was sold by members during visits to public houses. The Sally Anne has had a presence in Bourne since the closing years of the 19th century with their meeting halls at several locations including an old corrugated iron hut on the Abbey Lawn, the first floor of the red brick shop and workshop premises behind West Street now occupied by the stationery and printing firm Fovia Ltd, and at their present premises in Manning Road since 1990 after planning permission was granted despite an objection from one resident living nearby who complained that they might be disturbed by “the frequent sound of their brass bands”. Such is their reputation for producing rousing melody, both sacred and secular. It was General Booth himself who popularised the saying “Why should the devil have all the best tunes?” and as Salvationists regard music as one of God’s most valuable gifts to mankind, it has always played a major role in their activities, hence this most enjoyable Christmas concert while out shopping on Saturday. Thought for the week: Brass bands are all very well in their place - outdoors and several miles away. - Sir Thomas Beecham (1871-1961), English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras and a major influence on musical life in Britain. Saturday 15th December 2012

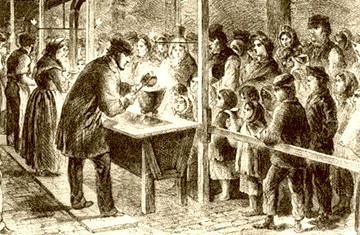

We live in an affluent society yet few of those who enjoy the fruits of this prosperity really know or care how the other half lives. A comfortable home, annual holidays abroad and dining out are all taken for granted but we have a growing underclass that enjoy none of these luxuries and depend for their very existence on hand outs. It was widely believed that social deprivation would end with the creation of the welfare state which began to emerge in the early years of the 20th century, a concept of government based on the principles of equality, the equitable distribution of wealth and a public responsibility for those unable to provide a good life for themselves, and yet 100 years later the gap between rich and poor has widened and the number that need state help increases annually. It is against this background that we need to appraise the current government policy of spending cuts which target the less well off, especially those struggling to survive on low wages and drawing benefits because they have become the nation’s new poor. Many cannot afford to keep warm because of soaring heating bills while the easing of hunger is a daily problem as the £ slowly loses its value and food prices increase almost weekly. In the 19th century, these luckless people had to resort to the soup kitchen while today it is the food bank that has become their lifeline. These outlets for free food began to appear in the United States almost fifty years ago and are now evident in many parts of the world, even in England, usually non-profit making charitable organisations that distribute provisions to those who have difficulty in buying enough to avoid hunger and there has been a rapid growth in them as a result of the austerity imposed by the government in the wake of the current financial crisis. Almost half of those who use them have had problems with their benefits, are on low income jobs or are struggling with debt repayments and other expenses and the demand for even more food banks is expected to increase further when the latest welfare cuts come into effect next year. Most food banks in this country are run by the Trussell Trust and manned by volunteers from local churches who give out provisions directly to the hungry. About a third of their supplies come from supermarkets although much of it is donated by individuals. The trust was formed in 1997 to help forgotten people such as the homeless children sleeping rough in Bulgaria and eventually spread to the United Kingdom, expanding its activities to all people facing hunger because of a short term crisis and there are now more than 200 food banks in this country which last year fed more than 128,000 people. They exist in many local towns including Stamford, Spalding, Grantham and Peterborough, and as the recession continues to bite, we are now to have one here in Bourne. Churches in the town have been working with the trust to establish a centre for storage and distribution which is expected to open early next year. One of the organisers, the Rev Andy Warner, minister at the Baptist Church in West Street, told The Local newspaper that the project was already taking shape (December 7th). “Our intention is for a food bank to be ready around Easter”, he said. “This is all about our local community pulling together to help those most in need and signposting them to appropriate agencies to improve their situation.” The Bourne project is being actively supported by Tesco which has a store in South Road where the company’s policy of food collection is already underway. All donations will be topped up by 30% as well as providing funding to enable the distribution organisations build on their work. The soup kitchen was the forerunner of the food bank that we know today, soup being a cheap and efficient method of distributing nutrition to people in need because it can be prepared comparatively cheaply in large quantities and therefore became popular as a means of feeding huge numbers of people in times of deprivation, particularly during the 19th century. Soup kitchens were established whenever conditions were hard or the weather inclement for long periods, providing a place where food was offered to the poor free of charge or at a reasonably low price. They were usually funded by wealthy citizens or religious and charitable organisations as an act of philanthropy and in Bourne, they were set up at suitable locations such as the Town Hall, staffed by volunteers from church groups and elsewhere. The notorious American gangster Al Capone financed a soup kitchen in the United States during the Great Depression, possibly to improve his image, while in London, the Islington Soup Kitchen founded in 1863, served a total of 7,031 quarts during the winter of 1903-04 and a similar amount the following winter. Soup kitchens can still be found in many countries in poor neighbourhoods as a service to the deprived members of society. Until 100 years ago, bread was the staple diet for most ordinary or labouring families and a survey of 1860 discovered that many adults consumed around 12 lbs. every week. It was often made more palatable by being covered with dripping or, very occasionally, a little butter. Small quantities of bacon, salt pork, beef, cheese and porridge also formed part of many poorer people’s weekly diets although such nourishing foodstuffs were more frequently reserved for the man of the house who needed to keep up his strength to maintain the family’s income. Pea soups or weak broths were other standbys for poor families and surprisingly, milk was in short supply, even in country areas, as many farmers chose to feed butter or skimmed milk to their pigs and calves. Even late in the 19th century, many women, and often their children, had to survive on a monotonous diet of bread, lard, vegetables and very weak tea. Some of our ancestors who fell on really hard times and ended up in the workhouse often ate better than the poorer workers in their own homes with a regular and more balanced diet although it may have been dull and boring by today’s culinary standards. Potato soup for mass consumption was an example of the food provided by some workhouses and a menu was published in an 18th century pamphlet, Information for Overseers, and quoted by the Stamford Mercury on Friday 31st January 1800 after being recommended by a Mr Turnor at the Bourne Sessions held at the Town Hall. It was prepared as follows: Put an ox’s head, well washed, into 13 gallons of water, add a peck and a half of pared potatoes, half a quartern of onions, a few carrots and a handful of pot herbs, thicken it with two quarts of oatmeal (or barley meal) and add pepper and salt to your taste. Set it to stew with a gentle fire early in the afternoon, allowing as little evaporation as may be, and not skimming off the fat, but leaving the whole to stew gently over the fire, which should be renewed and made up at night. Make a small fire under the boiler at seven o’clock in the morning, and keep adding as much water as will make up the loss by evaporation, keeping it gently stewing until noon, when it will be ready to serve for dinner. The whole may be divided into 52 messes, each containing (by a previous division of meat and fat), a piece of meat and fat and a quart of savoury nourishing soup. The expenses of the meals are: ox’s head 2 shillings and sixpence; potatoes, onions etc 1 shilling and 1 penny; 2 quarters of oatmeal 11 pence; cost exclusive of fire and cooking: 4 shillings and 6 pence. At that time, the workhouse in Bourne was situated in North Street at the corner of what is now Burghley Street, then called Workhouse Road, and no doubt every drop was eaten with relish by the inmates because the old adage that beggars could not be choosers was never more true than for those who were unfortunate enough to have ended up living there. A soup kitchen was also set up in Bourne during a period of cold weather which halted work on the land in January 1861 when 324 families consisting of 500 adults and 700 children were fed weekly for a month, paying one penny a quart at each session. The Stamford Mercury later reported: “This most excellent soup was distributed to all of the necessitous poor who applied for it and no doubt good service has been rendered to many persons who have suffered from the inclement weather and want of employment.” In January 1864 there was a similar crisis and a public meeting was held at the Town Hall to collect donations from wealthier citizens to pay for a soup kitchen which subsequently operated on three occasions. “About 60 gallons of soup of excellent quality have been served out at a halfpenny a pint to a large number of applicants”, reported the Stamford Mercury. “About a dozen subscriptions have been opened, one at each of the banks and others with various tradesmen, where it is hoped that those who desire to support the soup kitchen will leave their donations and thus avoid the necessity for a house to house collection.” Today, soup kitchens survive to help the homeless and destitute in many parts of the world while for the rest of us, soup is considered to be a small luxury rather than the necessity of past times, bought in tins at the supermarket or as a first course when dining out. Next time you tuck in, remember that it was once a lifeline for the poor. It has never been determined exactly why people shun society and choose the life of a recluse but it is usually related to past experience of people and an acute desire to be alone. Such a course of action is less likely in our welfare society when neighbours, council officials or the police feel it their duty to intrude if someone has not been seen for a while and so anyone who shuts themselves away can now expect a knock on the door after a few days to ensure that all is well. There are exceptions such as the case of Walter Samaszko, aged 69, who was found dead at his home in Carson City, Nevada, USA, last September. He had been dead for at least a month when neighbours raised the alarm and the house was found to be crammed with stuff that he had collected over the previous forty years with only enough room to crawl from room to room. But the surprise was that although Mr Samaszko only had £120 in the bank, the hoard included a treasure trove of gold bars with rolls of $20 bills and a mass of collectable coins worth a total of $7 million. Such is the stuff of fiction. We have had a similar case in Bourne although it happened over two centuries ago and our recluse was not quite so rich although in view of the poverty of the time, the wonderment at this happening in such a small town must have been just as great. James Quanborough worked as Collector of Tolls in Bourne during the late 18th century, his job being to collect the fees paid by stallholders at the weekly market and hand them over to the Lord of the Manor who held the market rights, then the Marquess of Exeter. During that time, he had no other support than on market days, filching and picking up potatoes, carrots, cabbage and beans from the stalls which he took home and boiled together with a handful of grain, and this was his existence for forty years. In September 1790, he was found dead in bed after neighbours raised the alarm and broke into his cottage. He was 102 years old and the Stamford Mercury reported on 1st October 1790 that he was in a terrible state, not having shaved for fourteen years and for the previous seven years he had not even been out of his room. Yet a search of the house found more than £300 hidden in different places, cash that would today be worth almost £40,000. James Quanborough was therefore wealthy but whether he died a happy man is a matter of conjecture. Thought for the week: The mind can weave itself warmly in the cocoon of its own thoughts, and dwell a hermit anywhere. - James Russell Lowell (1819-91), American poet, essayist and diplomat. Saturday 22nd December 2012

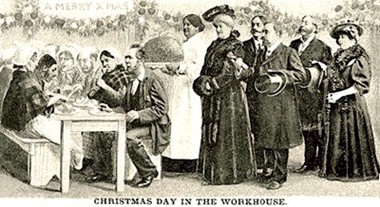

A popular dramatic monologue performed at smoking concerts and in the music halls of Victorian England was a heart rending account of poverty among the working classes called Christmas Day in the Workhouse. It was written in 1879 by George Robert Sims as a criticism of the harsh conditions in workhouses that had been established throughout the country. Sims (1847-1922) was a playwright and poet whose work raised public awareness of the suffering poor to such a level that he was appointed to study social conditions in deprived areas and to give evidence to a royal commission on working class housing. Christmas has a particular poignancy for the poverty stricken and the workhouse epitomised social deprivation, earning its place in English history as the last resort for the poor and destitute. The conditions that prevailed have been immortalised by Charles Dickens in his novel Oliver Twist, written against the background of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 which ended supplemental dole for the impoverished and forced husbands, wives and children into separate institutions in the name of utilitarian efficiency. Until then, each parish was responsible for providing relief to deserving cases but the burden on the rates was becoming heavy and the relatively easy terms on which men without an adequate wage could get financial help from public funds was being regularly abused. The government therefore decided to impose a more rigid procedure and the new legislation decreed that able-bodied men who could find no work had no option but to enter the workhouse, taking their families with them although in some cases, children were boarded out with foster parents. This was the main principle of the act that also required parishes to be grouped together as unions with a workhouse for each. Bourne Poor Law Union was formed on 25th November 1835 and a Board of Guardians to supervise the system was elected, a total of 44 in number representing 37 constituent parishes, and they lost no time in establishing the new regime that became operative by the end of 1836. The town already had a workhouse in North Street near the junction with Burghley Street which was then called Workhouse Road but this was too small to cater for the legislation and so a new building was planned at the end of St Peter's Road. It was designed by Bryan Browning, the architect responsible for the Town Hall, and built in 1836 at a cost of £5,350 with room for 300 paupers but was rarely full because admission was discouraged by the guardians. They enforced a strict regime in a bid to persuade the poor to seek employment rather than live in such grim and uncongenial surroundings. In 1881 for instance, the workhouse had a total of 123 officers and inmates and the guardians were meeting once a week to perform their duties. The staff included a master and matron, usually a husband and wife team approved by the board, a medical officer, chaplain, schoolmaster and schoolmistress, to assist with the welfare of the inmates who were not generally treated with much sympathy. Productive work was not encouraged, rules were strict and the official policy of economy left no room for luxuries. An example of the conditions that prevailed can be found in the workhouse accounts which indicate that 5p per head per day was spent on the inmates and that included clothing. Outdoor relief was also provided for the poor in their homes, there being a great resistance to entering the workhouse and some who could not face the stigma took drastic action such as inflicting self-harm or even committing suicide. It was a hard life but there were treats on special occasions such as Christmas Day and in 1877 the inmates were provided with a dinner of roast beef and plum pudding and entertained by a local group known as the Bourne Amateur Minstrels and even given small presents from underneath a Christmas tree donated by Lord Aveland, a local landowner. These additional luxuries were usually paid for by wealthy townspeople who often dropped in on Christmas Day to see how their money was being spent, to receive the thanks of the inmates and to ensure that they appreciated what they had been given and it is this image that has been caught so evocatively by George Sims in his monologue, a picture of wealth and privilege against a background of poverty and ill-luck. The Christmas treats continued throughout the years and a description from 1923 tells us that the workhouse was decorated and the extra food included pork pie for breakfast, roast beef and pork, hare, and plum pudding for dinner, cake and jam for tea and afterwards the children received presents of toys while there were sweets for the women and tobacco for the men. The guardians also ensured that they were appreciative of this charity and one of them, an eleven-year-old boy, no doubt guided by matron, wrote thanking them for providing such a happy Christmas and the lovely toys which Santa Claus had brought them. The letter concluded: "From one of the grateful little boys." In 1863, the name of the institution was changed from the Bourne Union Workhouse to Waterloo Square in an attempt to remove the stigma attached to the original address, especially among unmarried mothers who often gave birth there. The disgrace of the workhouse system remained until improvements in social conditions brought about its gradual decline and in 1930, the premises were converted for use as a mental hospital known as the Bourne Public Assistance Institution. It was also referred to as Wellhead House but subsequently became St Peter's Hospital for mentally handicapped women and children. This facility was slowly run down during the late 20th century and patients moved out under the government's policy of care in the community. The buildings stood empty until 1997 when the complex was bought by Warners Midlands plc, the printing firm that owns the adjoining premises, for an expansion of their business interests and demolished in 2001 and the site is now occupied by the company’s press hall and bindery. Christmas at the big house was a complete contrast because the festive season was also the time when the landed gentry remembered their servants and those who worked on their estates. It has been a tradition in England since the earliest times to relax the disciplines needed to administer the mansions and country houses and to allow a little merrymaking among those who kept them running and in good order. In 1866, for instance, there were festivities at Bulby Hall, near Bourne, as reported by the Stamford Mercury: The Hon Gilbert Heathcote MP, with his usual liberality, gave his servants and their friends a ball. Nearly 100 enjoyed themselves, the strains of Mr Wells' band and the refreshments being much appreciated. At nearby Grimsthorpe Castle, as befitted a grander house, the celebrations were far more elaborate when their party was held on New Year's Day in 1867: A ball was given by Lord Willoughby de Eresby to the servants and employees on the estate. Nearly 200 assembled about nine o'clock in the great hall which had been magnificently decorated by Mr McVicar, the head gardener. Amongst the decorations worthy of notice were a single branch of mistletoe seven feet high and twenty feet in circumference (this is a very uncommon size), the flags of the Lincolnshire Volunteers of the olden time when they were commanded by the Duke of Ancaster; and the ensigns and flag belonging to his Lordship's yacht. The band of Mr Wells, of Stamford, attended. After a few preliminary dances, the guests adjourned to an excellent supper. His Lordship's health was drunk with an enthusiasm well worthy of the place and the occasion. After supper, the dancing, interspersed with one or two well-sung songs, was kept up till six o'clock, the visitors at the Castle entering into the evening's festivities. Some of the gentry were also aware of the impoverishment that existed in the countryside as this report from the Stamford Mercury on Christmas Eve, Friday 24th December 1880, illustrates: The Rev Henry Prior, Vicar of Baston, has received £5 from Lady Willoughby de Eresby to be expended in coals for the poor of Baston. Miss Bothamley, of Pelham House, Kingston-on-Thames, has also sent the vicar £1 10s. for the same object. Despite this seasonal largesse, discipline below stairs remained harsh and many a maid and footman knew the hardship of dismissal, even at Christmas, if they were caught in the slightest misdemeanour or breach of the house rules. We live in an increasingly secular society and even the Church of England is split in its beliefs yet continues as our officially established Christian church and the mother church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Fortunately we have moved on from those times when weekly worship was compulsory on pain of prison, torture and even death and so we can more or less please ourselves whether we attend and our adherence to the faith may now be based on knowledge and experience rather than the blind faith demanded in past times. There are reckoned to be 16,247 Anglican churches in England but only 6% of the population actually attend services regularly (2008 church census), mostly older people, and the average Sunday congregation is around 50, a steady decline on previous years. In other words, religion is going out of fashion. Nevertheless, the churches in this country remain standing monuments to the Christian message, beacons of faith in a land where independent religious thought is a freedom. They also act as the centrepiece of our communities, a place where the people gather for celebration and mourning and so it is right that we keep them in good order for future generations as an example of the way it once was. Fortunately, most churches have a dedicated band of helpers who spend their time raising funds and doing the work to ensure that these historic buildings survive while few of us refuse a donation in time of need because we are all aware that there are occasions during the year when they are full because certain events attract those on the fringe of religion such as weddings and funerals, Remembrance Sunday and, of course, Christmas. We know how it was in years past because contemporary accounts exist and we have this description of the festive season at the Abbey Church in 1887 from the Stamford Mercury: Bourne Abbey was throughout adorned with seasonable decorations for Christmas. Though not so elaborately ornamental as in some previous years, the general effect was exceedingly pleasing. Over the communion table in white letters on a scarlet ground was the text "Emmanuel, God with us". The centre was occupied with a beautiful white cross. The miniature arches were filled with a pretty arrangement of evergreens interspersed with flowers. The reading desk was decorated with ivy and holly, the panels in front being ornamented with chrysanthemum crosses, the centre one of the St Cuthbert type. The pedestal of the lectern was gay with a choice selection of flowers and evergreens, a fine bunch of pampas grass being especially noticeable. Holly berries and ivy embellished the handsome pulpit. The sills of the windows in the north and south aisles were beatified with texts worked in white on a scarlet ground, and encircled with wreaths and evergreens. The font was decorated with exquisite taste; the cover was surmounted with a fine cross and chrysanthemums; the pedestal was encircled with ivy and a variety of evergreens prettily frosted. Great praise is due to the ladies who so admirably executed the decorations. Christmas was ushered in at Bourne with merry peals of the bells of the old abbey church and the musical strains of the Bourne brass band who played carols and other appropriate pieces in an exceedingly creditable manner. I was brought up in the Christian faith and the many years I served as a choirboy familiarised me with its ceremonial and traditions and to attend a choral Christmas service in a village church is still a moving experience although this season of goodwill owes more to Mammon than to God and much of our celebration today goes no further back than Victorian times with its images of plum puddings and port, the sale of plump birds, carols, cards, crackers and decorated fir trees. Apart from the New Testament, A Christmas Carol must be the best-known Christmas story in the world and Dickens asks us to believe not so much in God as in ghosts and a detailed study of this work reveals it to be a text of 19th century humanism. Despite this universal scepticism, this is a time when families gather and old friends meet, to exchange presents, to chat and to eat and drink together and to remember times past which is as it should be. We therefore wish you all a very happy and enjoyable Christmas and a healthy and prosperous New Year when we expect this column to be back with more thoughts about the way we live now. Thought for the week: Christmas is not a time nor a season but a state of mind. To cherish peace and goodwill, to be plenteous in mercy, is to have the real spirit of Christmas. - Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933), farmer, storekeeper and public servant who became the 30th president of the United States. Return to Monthly entries |