|

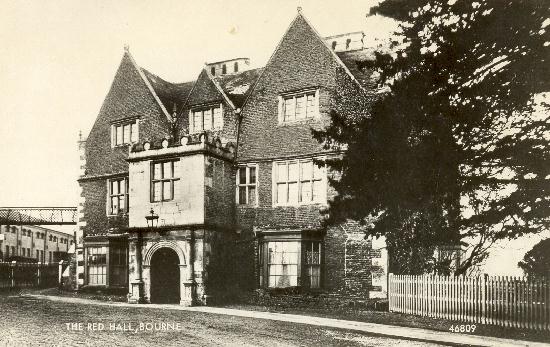

The Red Hall

The architect and builder are unknown yet their legacy remains with the Red Hall which dates back to the early 17th century. It has a chequered history as a home and institution, even as part of a Victorian railway complex, yet survived 100 years of vibrations from steam locomotives and rolling stock to become our most famous secular building which has been Grade II* listed since 1977. The house is believed to have been built for a wealthy

businessman, Gilbert Fisher, and is typical of the new style of residence being

constructed for prosperous gentlemen of the early Stuart period, remaining in

his family for almost a century although the evidence is that the high costs

involved also put them deeply in debt because the building was heavily mortgaged

for several years afterwards and the liabilities were not finally settled until

the family vacated the property over ninety years later. The building of the house is not documented but construction is assumed to have been between 1600 and 1610, with 1605 being the favoured date. There is, however, a theory that it could have been a decade before, suggested by David L Roberts in his pamphlet (undated) which appraises John Thorpe's designs for Dowsby Hall and the Red Hall. "It would appear improbable that the rather coarse quality of the Red Hall could be contemporary with the relative polish of the work at Dowsby", he writes, "and an earlier date, possibly nearer 1595, might be more appropriate. Could Sir William Rigdon have built the house and then sold Dowsby to cover his expenditure?" No documentary evidence survives to identify the builder but the first tenant was undoubtedly Gilbert Fisher, a London grocer, who had amassed a sufficient fortune to finance such an ambitious project that would give him a standing in the community. He was the son of Richard Fisher, who died in 1597, who had been chief constable of the hundreds or wapentake [an ancient division of the county] and was therefore a man of some importance while his son had made a success of his business and was classed as "a gentleman" in the parish register. The house, as with Dowsby, was set within formal gardens and the design was conceived on the double pile principle with rooms two deep, a practice that was less common than the more traditional design of a hall with one or two cross-wings and two storeys with garrets. The walls are made of locally produced hand-made bricks of a distinctive deep

red with stone detailing and ashlar quoins, hence the name, and the original

intricately carved oak staircase with attractive turned balusters remains intact. The house is many gabled

and has a fine Tuscan porch. The four main rooms on the

ground floor comprised an entrance hall and dining parlour at the front with the

kitchen and buttery-cum-pantry in the rear. Above these, on the first floor,

were four bedrooms, while on the second floor, running right across the front

half of the building, was the high gallery. It is interesting to see that the two main living

rooms downstairs were without beds, as we would expect them to be nowadays, but

in that period it was still quite usual to find parlours that were used for

sleeping in. It is therefore apparent that Gilbert Fisher and his family were

well up with changing trends. There were also a number of outbuildings

attached to the Red Hall, the most important of these being a kitchen or

scullery, a brew house, and a dairy. However, life was not without its difficulties and Fisher died in debt, his goods totalling £663 13s. 4d. but his liabilities and funeral charges exceeded that amount and he owed, £282 2s. 4d. to the Earl of Exeter and £45 10s. in rent to him as well as other small debts. He also had his share of bereavements. A son, also Gilbert, was born in December 1610 and died the following May. His wife, Catherine, was buried in August 1612 but he married again and in 1615 they had a son, John, who was baptised and buried a week later. Another son, also Gilbert, was christened in 1616 but he too died when he was nine years old. The couple had several more children and one of these died in childhood, another was buried five days after her baptism. After Gilbert Fisher's death in 1633, his family remained in occupation until 1698 when the Red Hall was sold by his grandson, also Gilbert Fisher, first to Richard Dixon and then to Richard Warwick and subsequently passed into the hands of the Digby family when James Digby (1707-51) married Warwick's daughter and heir, Elizabeth, circa 1730. After James died, his eldest son, John, became tenant and when he died in 1777, ownership passed to his younger brother, James. He achieved some distinction in the county, becoming Deputy Lieutenant of Lincolnshire, clerk to the Turnpike Trust for the south east district of the road between Lincoln Heath and Peterborough and treasurer of the Black Sluice Drainage Commissioners. James Digby was also twice married, firstly to Mary, daughter of Francis Green, of Dowsby, in 1757 but she died in 1792, and in 1796 when he was 60 years old, he married Catherine, 23-year-old daughter of the Rev Humphrey Hyde, Vicar of Bourne, and it was to the Red Hall that he brought his young bride who was 37 years his junior where they seem to have lived in some style and comfort with many servants and a wine cellar stocked with fine wine and port. James Digby outlived his two other brothers, George and Richard, and by the time of his death in 1811, he had built up a considerable estate in Bourne and Dyke and a fortune reputed to be around £200,000. The Red Hall and a portion of his lands remained in the possession of his widow, then known as Lady Catherine, together with a legacy of £500 and an annuity in the same sum, until she died in 1836 when under the terms of her late husband's will, ownership passed to his youngest sister, Mrs Henrietta Pauncefort. An inventory of the Red Hall from this time also survives to give a glimpse of the way the family had lived during the early 19th century. The ground floor rooms were now known as the hall, drawing room, dining room, breakfast room and kitchen while the next floor comprised four bedrooms, three of them being designated by colours, namely green, yellow and blue. On the top floor was a storage garret and rooms for the men and maid servants. The rooms, as in a previous period, seem to have been somewhat over-furnished, the dining room containing mahogany and claw furniture with two ottomans and a dozen chairs. In the drawing room were a sofa, two ottomans, numerous small tables, seven elbow chairs and four Swiss chairs. Four-poster beds with hangings were still to be found in the bedrooms upstairs while there was a six-foot bath in the closet. There is evidence that the next tenant was Charles Sleith Esq, the Red Hall

being described as his seat in 1841 in Pigot and Company's Trade directory for

that year, and it is assumed that the property was leased to him and ownership

remaining with the Duncomb family. Duncomb died in 1849 and his property was

inherited by his son, also named Philip Pauncefort Duncomb, who lived in

Buckinghamshire. For ten years, the Red Hall was leased for use as a private boarding

school for young ladies, firstly under the direction of Miss Elizabeth Sardeson

and then Miss Eliza Wood, and in 1859-60 Duncomb sold the property, together with the adjoining buildings and five acres

of land, to the Bourne and Essendine Railway Company for £1,305 and so it came

about that the town's railway station arose almost on the doorstep of this

famous building. They had lit a fire in the fireplace to keep warm but there had been a large quantity of wood and other rubbish in the chimney, probably lodged there by jackdaws while the hall was unoccupied, and this caught light, the flames then spreading to a large beam and to several of the floor joists. A fire brigade official said that the blaze could easily have spread to a quantity of old timber that was lying around the premises and had the outbreak occurred a few hours later when no one was about, it was probable that the entire building would have gone up in flames.

The Red Hall was eventually converted for use as

the stationmaster's house and ticket office for the railway line but in 1891,

the Great Northern Railway Company decided to extend the installations at Bourne

and to demolish the building to make way for new sidings. This provoked an

outcry, not only in the town but throughout the country, and a petition to the

directors endorsed by local citizens and conservation groups was raised in an

attempt to save it. On Friday 18th December 1891, in response to the petition or

memorial as it was called, the directors came to Bourne by special train to

inspect the property with the result that the decision was eventually reversed. This was regarded as uneconomic and the company began looking around for new uses to which the property could be put and a local clergyman, the Rev Gerald Davis, Vicar of Thurlby (from 1925-31), applied to lease the house with a view to it being restored and used partly as a museum and partly as headquarters of a local welfare society, the public being allowed to inspect the property at reasonable times. Mr Davis told the railway company that he would find alternative accommodation in Bourne for the railway staff and their families and a 21-year lease was agreed at a peppercorn rent of £1 a year but he was unable to find anyone who would act as trustees who were prepared to accept responsibility for restoring the house and the local authority, then Bourne Urban District Council, also refused to become involved and so the scheme was dropped. When the station closed in 1959, the future of the Red Hall again came under review and the company expressed an intention to give the building away but no one wanted it and many councillors, including some from Bourne, suggested that it should be left to fall down. But help was at hand, notably through the efforts of the late Councillor Jack Burchnell, and after a long and determined fight, he ensured that Bourne United Charities acquired the freehold in 1962 and they remain the owners to this day. The hall was in a dilapidated condition when they took over, the chimneys having been dismantled in 1957 because they had become dangerous although the remainder of the building was intact, and with the aid of local funds and grants, it was carefully and sympathetically restored to its former elegance under the guidance of the Lincolnshire architects Bond and Read and re-opened in December 1972 as a museum, community centre and the offices of Bourne United Charities.

Most visitors see only the front facade of the Red Hall and few take the trouble

to walk round and inspect it from the back. It is equally attractive from here

and despite the financial problems it created for Gilbert Fisher, we are

grateful for his architectural legacy that has become one of the delights of

this small market town. The Red Hall must be one of the great treasures from

17th century England because the exterior and, more particularly the interior,

have remained relatively untouched for 500 years. This room is the finest of all in the Red Hall, still redolent of its past, and to walk its length is to experience an expectation of meeting past occupants. The long gallery and upper rooms have been refurbished in recent years but the work has been so well executed that it is hardly noticeable except for small plaques that remind us of recent philanthropy, one on the top floor hallway (left) and another inside the door of the long gallery:

Further restoration has been carried out in the boardroom where the trustees of Bourne United Charities hold their regular meetings to administer the various funds under their control. A small plaque here says:

Gardner, a former trustee. was also a talented artist and four of his framed watercolours are on display in this room.

The Red Hall continues in use today as the headquarters of Bourne United Charities but rooms are also used for a variety of functions by local groups and conservation organisations. The attractive period appearance also makes it a magnet for visitors and it must be one of the most photographed buildings in Bourne, almost as famous as the Abbey Church itself. It is not, however, easily accessible for public inspection. Visitors are unable to make a tour of the building without prior arrangement with Bourne United Charities and its interest is therefore restricted. Other public buildings such as the church, the Heritage Centre and Wake House, may be seen during opening times but no such facility exists at the Red Hall and its beauty is therefore only seen from the outside. THE RED HALL GATEWAY

The gatehouse

to the Red Hall is now a private house, standing in South Street at what

was the entrance to the drive. The cubic building has lancet windows and

was originally finished in the same distinctive hand-made red bricks but

the outside walls have been rendered and painted and turrets which adorned

each of the four corners of the roof were removed during the early part of

the 20th century. As with the Red Hall itself, this is Grade II listed

as is the section of wall with pyramidal caps on the two pillars

that can be seen on the left of the building.

See also The myth of the Gunpowder Plot The Red Hall ghost Past owners of the Red Hall The Red Hall in Past Times Catherine Digby Thomas Glendening The petition of 1891 Bourne United Charities Disposing of the Red Hall The 1972 re-opening The 1976 Tudor exhibition The 1981 Heritage exhibition The R A Gardner art exhibition of 1996 More photographs of the Red Hall

Go to: Main Index |

||||||||||||||||||||||