|

The village school and

the 1881 sampler

|

|

|

|

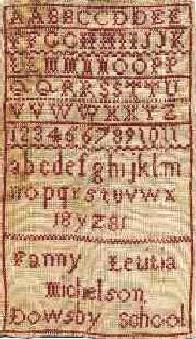

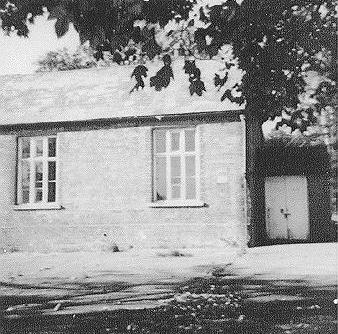

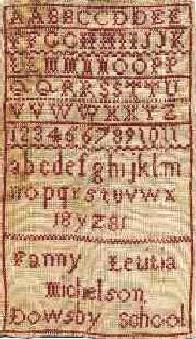

The wool and linen sampler stitched by Fanny

Michelson in 1881 and the school she attended, now converted into a

private home. |

In centuries past, children were

meant to be seen and not heard and so parents, governesses and teachers

devised various methods of good works to keep them occupied. For the

girls, sewing was high on the list of activities that could be pursued in

silence and at the same time, taught a craft that would be useful in later

life.

The sampler came to be regarded as an essential part of a young woman’s

education because it provided a record of all the stitches and patterns

that a housewife would require and as pictures of houses, churches, trees

and flowers were added, they became works of art when finished in silk

thread on linen. Among the more common inscriptions are prayers, moral

maximums and biblical texts, often showing a preoccupation with death and

misery, although less depressing subjects can also be found such as those

depicting maps and major events although these are particularly rare

because of their value as social or historical documents.

The most beautiful specimens of original sampler work that have survived

belong to the 17th century and in consequence are rarely found outside

museums although the 18th century did see some fine examples which are

highly collectable. In later years, they were framed for their artistic

value and many were indeed triumphs of decorative needlework which are

highly prized by connoisseurs and collectors. The fashion for using Indian

cotton resulted in many designs with bright floral patterns although the

variety of stitches had decreased by the end of the 18th century when

cross-stitch alone appears to have held the field and this became known as

the sampler stitch.

Sampler making was a common subject on the curriculum of the early state

schools of the 19th century and, with typical Victorian sense, alphabets

and numerals were usually the prescribed patterns in order that children

would learn two subjects at once. Because of the large number of

participants, materials were necessarily cheaper and brightly coloured

wools were employed on meshed canvas and more ambitious designs such as

landscapes and animals, often cleverly shaded, were made possible by the

use of coloured embroidery charts, although these niceties are usually

absent in classroom designs which tend to be more mundane.

The inscriptions on samplers are a literature in themselves and an

intriguing record of the precepts of child education during that period.

One such example from the Bourne area has been acquired by Jacqueline

Holdsworth of Guildford in Surrey, who bought it from an antiques shop near

Hanover in Germany where the owner said that he had picked it up about 15

years before at a street market in England. “I suppose I bought it because

it was in the wrong country and demanded to be brought home”, said

Jacqueline.

The sampler was the work of Fanny Letitia Michelson, a pupil attending the

village school at Dowsby in 1881. Education, as elsewhere in England at

that time, was entirely at the behest of local philanthropists and it was

the Burrell family of Dowsby Hall who founded and maintained a parish

school in the village during the 17th century when classes were held in

the vestry of St Andrew’s Church, a room that was later enlarged for this

purpose. This was replaced by an endowed or elementary school, built of

red brick and blue slate on land near the church in 1864 with room for 65

children although attendance was usually far less. The average number at

lessons in 1885 was only 42 but this had risen to 53 by the end of the

century. John Robert Holmes was headmaster and he was also the parish

clerk and the local collector of taxes and he was still in charge in 1904

although by that time the rector, the Rev Thomasin Albert Stoodley, had

taken over as parish clerk.

The school was financed with money raised by a local rate, a government

grant and an annual endowment of £10 from the estates of local landowners

and continued in use until it closed under the government re-organisation

of education in 1976 when the building was sold and it has since been

rebuilt as a private home. The village was also sufficiently prosperous at

that time to support a mill that survived into the 20th century, as well

as a boot and shoe maker, a grocer and beer retailer, but today all have

closed and there are no shops or services apart from a telephone kiosk.

Fanny's sampler contains the

letters of the alphabet in capitals and lower case, the numbers from 1 to

11, her name with the date 1881, and a few lines in cross-stitch. This is a

simple example of the art, a relic of elementary education during

Victorian times, worked in red wool and canvas rather than silk and linen,

and it has not weathered the years particularly well. But once its

antecedents are known, it becomes an interesting example of school work in

the late 19th century, one that Jacqueline describes as “a simple sampler,

not over-embellished, just plain and honest”, and although she does not

say how much she paid for it, in the right sale on a good day it would be

quite likely to fetch £20-£30. Whatever would Fanny have thought had she

known that her work would one day be that valuable?

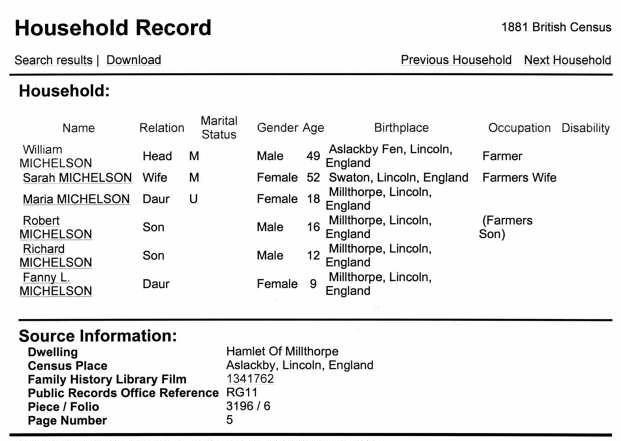

Research has revealed that Fanny was the

nine-year-old daughter of a farmer, William Michelson, aged 49, and his

wife Sarah, aged 52, who lived at nearby Milthorpe [also spelled

Millthorpe] and they had three other children, an 18-year-old daughter

Maria and sons Robert, aged 16, and Richard, aged 12. Milthorpe is not

marked on many maps because it is little more than a hamlet with a

population of 70 in 1881. It is almost a mile to the north of Dowsby and

in the absence of motor cars and public transport, we must assume that

Fanny had to walk to and from school every day along a country road or

perhaps taking a short cut by following farm tracks across the fields.

William Michelson was an established farmer

with land in Aslackby fen and is listed in Kelly’s Directory for 1876 and

again in 1886 although by 1904, his son Robert had taken over but we have

no idea what happened to Fanny after her schooldays, the most likely

eventuality being marriage or domestic service.

Michelson is a name that occurs frequently in the social history of the Bourne

area and descendants of Fanny’s family may still be alive. One of her ancestors

is almost certainly Robert Michelson who managed the Dowsby Decoy from

1763 to 1783. He and his wife Isabella lie beneath a pair of fine slate

headstones in the churchyard outside the south porch.

WRITTEN MARCH 2004

|

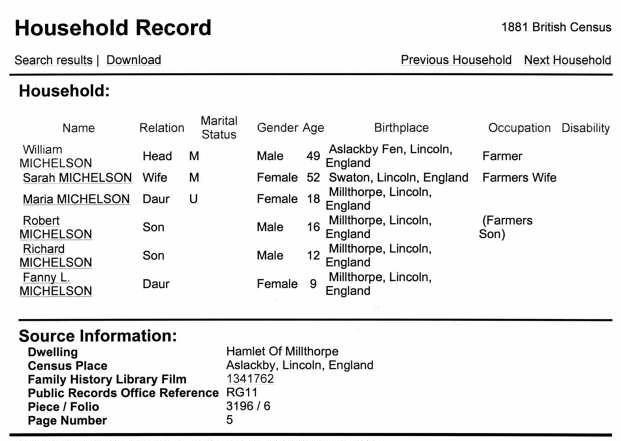

The Michelson family of Milthorpe as detailed in this

extract from

the 1881 census provided by the Public Records Office |

|

|

See also Milthorpe

Return to Dowsby

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|