|

Burials in the

churchyard

The churchyard is regarded

as the last resting place of those who went before and has become the

focal point of research for anyone anxious to trace ancestors from past

centuries.

This plot of secluded land to the south of the Abbey Church, shaded by

ancient chestnuts and lined with slate and granite tombstones, contains

barely 300 graves yet those who died in Bourne in past centuries are

numbered in their thousands and leaving us with the mystery of where they

were all buried.

Graveyards were usually established at the same time as the building of

the church which in this case is 1138, and were often used by those

families who could not afford to be buried inside the place of worship

itself. The nobility and those who were wealthy and important, usually

landowners, were given crypts or space beneath the chancel and the nave

and several ledger stones in the Abbey Church mark such graves, notably

Alice Hyde (1685-1737), John Hurn (1688-1757) and Hargate Dove

(1744-1810).

Most people from the middle or working classes were buried outside in the

churchyard, usually divided by social status, and families of the deceased

who could afford the work of a mason marked the grave with a headstone but

most could not although sometimes a religious symbol made from wood was

placed on the grave and as this quickly deteriorated in extreme weather

conditions, the graves eventually became unmarked. There were also

favourable locations according to who you were and as the entire

churchyard was not always consecrated ground, a practice persisted until

the 19th century whereby the virtuous were buried on the south side of the

church which received the most sunshine while felons, outcasts and

unbaptised infants were consigned to the perpetual shadow of the north

side.

By the mid-19th century, burials ended in the churchyard at Bourne

because, like many others around the country, it was deemed to be full.

There was no more space and some plots had been used two, three and even

four times for interments with bodies stacked one upon the other, a

situation which resulted in the opening of the town cemetery in 1855.

There were several different types of graves then in use, the private

grave on a specific plot of ground purchased by a person with the right to

erect a headstone or other monument, a common grave filled by several

unrelated persons who had died during a specific period but could only

afford the basic burial, a public grave several tiers deep but filled up

after each interment and a pauper’s grave paid for from public funds but

actually an unofficial form of the common grave and usually containing

several burials.

Other variations included an inscription grave which was a type of common

grave but sometimes had a headstone serving several plots for unrelated

deaths. We should remember however, that gravestones were a 17th century

innovation while most date from the 18th century or later and so for the

first 500 years of its life, the churchyard was filled with unmarked

graves. But a close inspection of the parish registers reveals that the

number of burials recorded over the centuries could never have been

accommodated in the churchyard alone even adopting such extreme measures

as the multiple use of grave spaces.

Overcrowding was evident well before records of burials began, even as

early as the 14th century when the high number of deaths during major

outbreaks of the Black Death reached unmanageable proportions. In 1349,

for instance, when the bishops were called upon to licence new churchyards

and extensions to the old, Bishop John Gwynell of Lincoln, while

dedicating a new churchyard at Great Easton in Leicestershire to

supplement that at the mother church at Bringhurst, told the people:

“There increases among you, as in other places of our diocese, a mortality

of men such as has not been seen or heard aforetime from the beginning of

the world so that the old graveyard at your church [at Bringhurst] is not

sufficient to receive the bodies of the dead.”

The earliest records of burials can be traced back to the mid-16th

century. There were 45 burials in 1562 and this figure had risen to 64 in

1600 with subsequent years showing a slow but steady increase. The

greatest number of burials in the 17th century was between 1633 and 1642

when there was a high rate of mortality in the town believed to have been

caused by the plague which was constantly breaking out in England from the

time of the Black Death to the Fire of London. A total of 662 burials are

recorded for that ten year period, the highest annual figures being 100 in

1634 and 126 in 1638.

An estimate for the long term can be assessed from the total figure for

the first half of the 17th century when 2,670 burials were recorded for

the years from 1601-1650. Replicating this summary would mean that the

churchyard had to cope with at least 5,000 burials for each of the

subsequent centuries although the death rate was increasing with the

rising population and so between 1562 and 1855 when the churchyard closed,

at least 30,000 burials would have taken place although with unrecorded

deaths prior to that, and in those years when no register was kept, this

figure will be much higher. Cremation is not a factor because this

practice was not introduced until 1902.

These figures are borne out by the National Burials Index (NBI) which

records a total of 37,624 burials in Bourne between 1754 and 1995 although

8,287 of these were in the cemetery which opened in 1855 and so the total

for the churchyard for that period will be 29,337. My own records go back

a further two centuries to include those burials between 1562 and 1753 and

so we are able to give a continuous total over five centuries of 50,000.

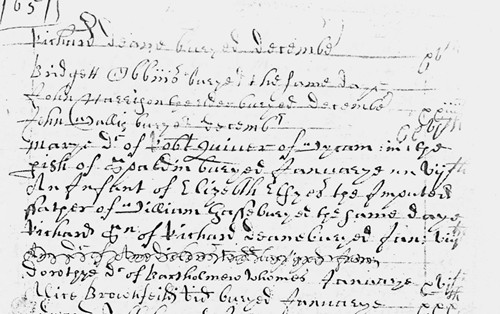

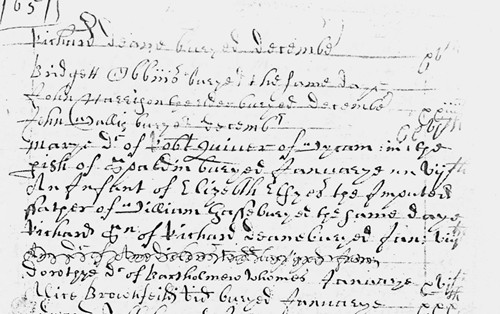

Extract from the Bourne burial register for 1651

A survey of the monumental inscriptions in

the churchyard by the Lincolnshire Family History Society (Bourne branch)

in 2010, revealed that there were 276 burials at the present time and the

earliest date appears to be 1710. Using the figure of 300 graves as a yardstick

therefore, this means that the churchyard must have been used 166 times over to provide space

for the departed in the 900 years of its existence which is quite unlikely

and so there must be another explanation, perhaps that mass graves were a

far more frequent occurrence than is recorded in our church histories.

They are still used in time of war, plague and disaster and it is the

simplest solution for any authority when faced with a large number of

bodies needing burial. There are many instances of this during times of

plague and epidemic, particularly during the Black Death period and with

frequent influenza and cholera outbreaks, when alternative mass burial

pits were dug well away from inhabited areas for fear of infection,

perhaps even out in the countryside, and this will account for many

discoveries of mass graves made when farming, building and other

modernisation projects are undertaken.

John Bland of the LFHS

thinks that even these figures may be an under estimation. “The death rate

potentially could be higher”, he said. “Non-conformists and Catholics

would have no place in the churchyard at times. Where would they have been

buried? Would their deaths even be recorded?”

He accepts the theory that the present churchyard is simply too small for

the population and has suggested that perhaps it was once much larger at

some time in the past but the only evidence of this is the marooned

tombstones on the south west side which indicate that those graves were

replaced when the footpath was built but this would not mean the loss of

many burial plots. The only other land available is to the east of the

present churchyard but there is documentary proof that this was offered to

the church in 1846 and refused and a major factor in the decision was

undoubtedly the Burial Act of 1855 which resulted in the establishment of

the cemetery in South Road, thus resolving the shortage of burial space in

the future.

Many church historians offer an explanation to the mystery by pointing out

that even in a small village of say, 250 inhabitants, several thousand

people died and were buried each century and in the average country

churchyard there are about 20,000 bodies under the soil. In some counties

such as Norfolk, the ground has even risen by as much as three feet often

giving the appearance that the church has sunk into the ground. This

explanation is apparent with the churchyard in Bourne which has also

risen above the level of the church for a height of more than 2 ft. although not quite so dramatically as others elsewhere in

the country but then this is

fen soil and the land is also liable to sink, thus reducing the impact.

The inadequacy of old records makes it impossible to trace the last

resting place of everyone who died in Bourne but this changed with the

opening of the town cemetery and all 10,000 burials that have taken place

there have been recorded for posterity. Death is an inevitable

eventuality with the annual numbers rising as the population increases and

despite the frequency of cremation which accounts for more than half of

the funerals today, even the cemetery in South Road is now running out of

space and the town council is currently negotiating to buy more land for

the future.

All burials today, however, are accurately recorded and anyone who has

been interred in the past 150 years can easily be identified through

reference to the burial register held by the town council. Seeking this

information from the period prior to that, however, can prove to be a

difficult even impossible task if we are to depend entirely on the parish

registers or what may be gleaned from the grave spaces in the churchyard

and it is unlikely that the secret of how many bodies have been buried

there over the centuries will ever be revealed.

REVISED NOVEMBER 2013

See also

Finding

space for burials in Bourne

Go to:

Main Index Villages

Index

|