Tragedy for a

young man with

a passion for speed

by REX NEEDLE

|

In the early years of the last century when Raymond Mays was striving to produce the perfect racing automobile, many aspiring drivers with a passion for speed made the pilgrimage to Bourne to try their hand at the wheel. Among the visitors to the workshops adjoining his home at Eastgate House was a young Oxford undergraduate, Francis Giveen, who was anxious to obtain a fast car but whose life was destined to end in tragedy. At that time, the fen roads around Bourne were perfect for the testing of racing cars and Mays took full advantage of them and because they were long and flat with little traffic about, he could use them without much interruption. His main interest at that time was hill climbs and so he had the added advantage of using Toft Hill on the way to Stamford, one of the most dangerous roads in the area, now a winding section of the A6121 with a steep incline and sharp double bend which runs from farmland on the uplands to the west of Bourne through the village and out into the open countryside, a distance of about one third of a mile. The hazards of driving this way are acknowledged by those who know the route and the many warning signs, both on the carriageway itself and on the grass verges, because a moment of lost concentration could end in disaster. It is therefore surprising to discover that Mays used this hill for his trials and not all of them were successful. In 1925, Mays sold one of his first models, a 1.5 litre Brescia Bugatti known as Cordon Bleu, to the young Giveen, then aged 18, who was new to motor racing and needed to be taught how to handle such a fast car and so Mays invited him to spend the weekend at Eastgate House to polish up on his driving in readiness for a hill climb race meeting later in the year, the opening event of the season at Kop Hill, near Tring in Hertfordshire. Giveen had already owned the Bugatti for two months but had found it difficult to handle such a fast, light machine and after several runs through the narrow lanes around Bourne, Mays decided to pit him against his favourite slope, Toft Hill, where they duly arrived one morning with friends and relatives to supervise the course and warn of any approaching traffic. Mays took Giveen as passenger for several fast runs which went off without mishap and then it was his turn to try himself. “He seemed quite happy and obedient to my strict instructions to do several runs and work up his speed gradually”, said Mays when recalling the event in later years. “But then he came in for some special racing plugs to give the car a full throttle effect. Cordon Bleu roared up the narrow lane emitting that lovely and unique exhaust note, round the acute left hand corner which was followed by a bend to the right. But as he was leaving the corner, Giveen skidded and, with his foot hard on the throttle, hit the right hand bank with a sickening thud, shot across the road broadside, hit the opposite bank and turned the car completely upside down.” Dead silence followed and there was no sign of life and those attending the trials rushed over to the crash scene. They lifted the car on its side and found Giveen underneath, alive and practically unscathed, saved by a small Triplex screen that had borne the whole weight of the vehicle while upside down and had so saved his life, while the car was hardly damaged except for a few dents. Mays spent another day with Giveen trying to give him confidence but was unhappy at the thought of him driving in competition. In the event at Kop Hill, he ran off the track while approaching a bend, leaped into the air, jumped a small sandpit and knocked over some spectators but miraculously rejoined the course and finished the race although he could remember nothing about it afterwards. No more cars were allowed to run that day and as a result of the incident, hill climbs on public roads in England were stopped for ever. Fortunately, no one was killed and all of those injured recovered but ironically, it was Giveen’s crash that sealed the fate of these classic events. In the spring of 1930, Mays received a letter from Francis Giveen saying that he was experiencing problems and asking for a meeting to discuss them. This was revealed by Mays in his book, At Speed, which was published in 1952 but later withdrawn from sale for reasons unconnected with this incident. The two men subsequently met and dined at the Grosvenor Hotel in London where they both presumably stayed the night. Mays was alarmed at Giveen's state of agitation and the following morning, on leaving his room, Mays met one of the porters who said: "Have you seen your friend, Mr Giveen, sir? He was walking up and down the corridor outside your room last night flourishing a revolver." Two days later, Giveen's body was found on the towpath alongside the River Thames at Medley Weir, near Oxford. He had apparently shot himself after taking a taxicab to the river carrying a double-barrelled sporting gun. An inquest at Oxford on Wednesday 21st May 1930 on Francis Waldron Giveen, aged 23, heard evidence by his father, Henry Hartley Giveen, a distinguished lawyer, who said that his son had health problems and had recently spent time in a mental home. The cause of death was given as shock and haemorrhage following a gunshot wound in the face and a verdict of suicide during temporary insanity was returned. The car, Cordon Bleu, survived for several years but was eventually broken up for spare parts while Mays went on to develop the BRM which eventually became the first all British car to win the world championship in 1962. He was awarded the CBE in 1978 for services to motor racing and died in 1980, aged 80.

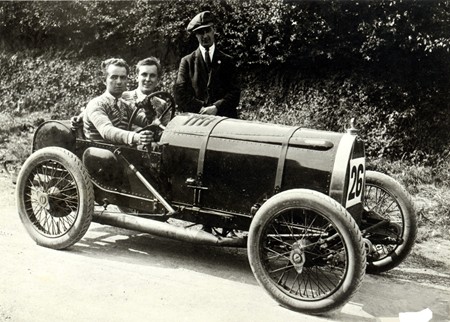

PHOTOGRAPH shows the 1.5 litre Brescia Bugatti known as

Cordon Bleu in 1924 with |