FIGHTING THE TERRIBLE PONG

FROM THE GLUE FACTORY

by Rex Needle

FIGHTING THE TERRIBLE PONG

FROM THE GLUE FACTORY

by Rex Needle

|

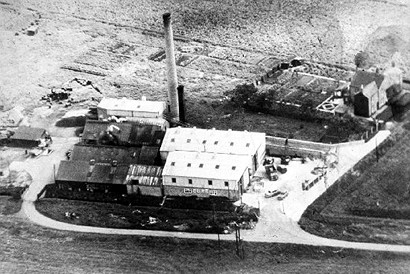

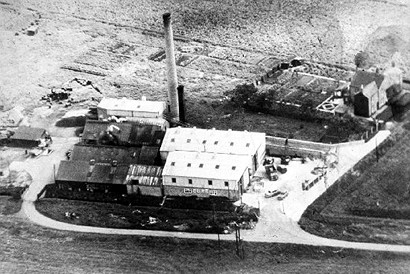

ONE OF THE GREAT eyesores of Bourne in recent years has been the former glue

factory at the Slipe in the South Fen, a monument to past industry that became a

victim of changing times and the buildings left to moulder and deteriorate as

the years passed them by. A local property company has now applied for planning

permission to redevelop the site as an industrial estate with six factory units

within the existing buildings and a further 13 in a new landscaped extension.

This is a most welcome initiative which will improve an unsightly area that has blighted the town for many years and at the same time create opportunities for those small businesses on which we depend to keep our local economy alive. The premises were previously occupied by an animal waste processing plant, also known as the solvent extraction or glue factory, which closed 30 years ago with a sigh of relief for those who lived here during the 20th century because during that time the industrial odours it produced were a constant problem, a nuisance which became known as “the terrible pong” that emanated regularly from the premises. The business was owned by T W Mays and Sons Ltd, a company with diverse agricultural interests, particularly fallen stock which was collected and processed at a slaughterhouse and skin yard on the banks of the Bourne Eau behind Eastgate and the meat and offal dealt with in a by-products factory while the manufacture of fertiliser was a major boost to its business. Carcasses of livestock such as horses, cattle and sheep were brought in by cart and it was the firm's proud boast in a tradesmen's catalogue of 1909 that "every atom of the carcasses reaching these works would be turned to some commercial account". The Slipe factory was run by a subsidiary company, Mays (By-Products) Limited, and was used to turn hooves, horns and bones into glue, a malodorous process and one that plagued the town, particularly during hot weather when the stink became so pungent that it wafted in from the fen whenever an east wind was blowing and penetrated shops, houses and schools and as a result, the premises soon became known as "the Bovril factory". For twenty years, townspeople put up with the smell and the company spent large sums on special equipment designed to reduce the nuisance and monitor its effects but to no avail. In February 1975, a local factory owner, Mr Colin Walker, protested to South Kesteven District Council that the smell was sickening and the stench from processing waste running into a dyke near to his premises so nauseating that his men were unable to continue with their work and several had threatened to give notice unless there was an improvement. But by the time his complaints was heard by the appropriate committee, the company had given assurances that the nuisance had ended and a representative was also sent to see Mr Walker to give assurances that it would not return. Mr A E Gooch, manager of Mays (By-Products) Limited, said: "We have assured Mr Walker that we will not let this happen again and we are co-operating to the fullest with the local authorities." But within a few months, the pong had returned and by the summer of 1978, Bourne decided that enough was enough and so many complained to the council that firm action became unavoidable. A report on the problem was drawn up by the Chief Environmental Health officer, Geoffrey Fox, and the environmental health committee met in July to consider it and decide whether the firm should be ordered to either curtail the nuisance or face an abatement notice which could have forced them to end production. The company fought back, saying that steps were being taken to reduce the smell and that they were monitoring the results but their new equipment was not yet fully operational and in the meantime, anything that was done to hamper production at the factory could jeopardise the future of the firm and the jobs of thirty workers employed there. But committee members were on fighting form and one councillor, the late Douglas Reeson, was unequivocal in his condemnation of the annoyance and even health hazard it was causing because he told the committee in an eloquent address: “Perhaps the firm has tried to do something about it but that does not help the people living in Bourne who have to put up with this stink. I live a mile and a half from the factory and can clearly detect it when the wind is in the right direction. The smell is quite appalling. One cannot explain just how abominable it is. I would like to be able to bring a sample of it here in a can in order that members can experience it for themselves. The people of Bourne cannot live with it whether there are thirty jobs at stake or not. I do not think that anyone should be asked to live with this sort of unpleasant odour. I feel very strongly about the possibility of people being put out of work but there are thousands of others living in this town who might reasonably expect some relief from this awful nuisance.” The committee voted unanimously that the situation could not continue and

agreed to give the company one last chance to end the nuisance. As a result, the

intensity of the smell was reduced although it was never completely eradicated

but eventually the problem was overtaken by events because the firm's prosperity

was not to last and the factory ceased production on 2nd March 1980 with the

closure of the T W Mays company's operations in Bourne. |

NOTE: This article was published by The Local newspaper on Friday 23rd April 2010.

Return to List of articles