The Bourne vicar's son who was hanged

for forgery

by REX NEEDLE

|

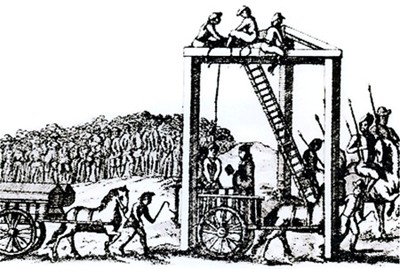

When great men go astray, the effects on family, friends and the community in which they live can be devastating. Such it was with Dr William Dodd, Anglican clergyman, man of letters and forger, whose career and ultimate fate caused a sensation in Bourne over 200 years ago. He was born in 1729, the eldest son of the Rev William Dodd who was Vicar of Bourne for almost thirty years during the early 18th century, and after graduating from Clare Hall, Cambridge, where he distinguished himself as a dedicated scholar, he moved to London in 1750 and the following year married a young lady named Miss Mary Perkins. Matrimony failed to suit and he spent some time as a man about town but his extravagant life style soon landed him in debt and worried his friends so much that they persuaded him to mend his ways and so he decided to take holy orders, a successful choice because he was ordained in 1751. For a time, he worked hard at his new occupation and became a fashionable and popular preacher, attracting large congregations at the Magdalene Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes where he was chaplain from its inauguration in 1758. Five years later he was appointed chaplain to King George III and soon after became tutor to Philip Stanhope, godson and heir to the Earl of Chesterfield. He also held several other ecclesiastical offices including Rector of Hockcliffe in Bedfordshire and Prebendary of Brecon and achieved some success as a writer with a volume of selections entitled The Beauties of Shakespeare (1752) which was reprinted many times. He also published a number of theological works including a commentary on the Bible and in 1766, Cambridge University conferred on him the degree Doctor of Laws. At this stage of his career, living in relative affluence, Dodd gave financial support to several orphanages and charitable institutions and was one of the original promoters of the Royal Humane Society, the organisation founded in London in 1774 to save life from drowning and to promote the use of artificial respiration. By now he had become well known in metropolitan society but was careless about money and living beyond his means. His waywardness in such matters resulted in continual financial difficulties and in 1774, in an attempt to rectify his situation, he tried to obtain the rich living of St George's Church in Hanover Square, London, by offering a bribe of £3,000 in an anonymous letter to Lady Apsley, wife of the Lord Chancellor, asking her to use her influence on his behalf. The letter was traced to Dodd's wife and subsequently shown to the king who was so outraged that he removed his name from the royal list of chaplains. The incident soon became the talk of London and made Dodd a target for ridicule in the press and even from the stage of the Haymarket Theatre and so he fled to Geneva in an attempt to escape the gossip. On his return, he was appointed to the living at Wing in Buckinghamshire and in February 1777, still short of money, he offered a stockbroker a forged bond for £4,200 in the name of Lord Chesterfield, his former pupil, but the forgery was immediately detected and he was prosecuted, sent for trial, convicted and sentenced to death. He made an abject appeal to the court but this failed, as did the efforts of influential friends to secure a pardon. Dodd was committed to Newgate Prison to await execution and among those he appealed to was Dr Samuel Johnson, the dominant figure of London literary society in the 18th century. Subsequent exhortations addressed to the King, the Queen and other prominent people of the day, and a petition signed by 23,000 people urging clemency, were all unsuccessful and on 27th June 1777, Dodd was publicly hanged. The execution took place at Tyburn Tree, the mass gallows at the junction of Oxford Street and Edgware Road in London from the 12th century until 1783, where there were three horizontal beams that could hang eight men at once. It was a most ignominious end for the son of a clergyman and although an attempt was made to revive the corpse afterwards, it was not successful. Public hangings at that time were a favourite haunt of the resurrection men who supplied surgeons with recently dead bodies for dissection, the practice then being illegal, and Dodd's corpse was delivered to the home of John Hunter, anatomist, collector, surgeon and teacher, who is reputed to have dissected thousands of bodies in his search for knowledge, mostly delivered under cover of darkness. It was a grim trade with body snatchers fighting over the corpses of hanged felons and more than once the victims sprang to life again on the anatomistís slab. When Dodd's body arrived at Hunterís house, the surgeon immediately tried to revive him but he had been dead too long before the surgeon began to pump air into his lungs with a pair of bellows and he could not be brought back to life. During his time in prison, Dr Dodd had begun writing poetry in a notebook that has survived although most of his other manuscripts were lost. They were most probably sold when his possessions were auctioned after his death by his creditors who opened and read out items from his private correspondence with his wife for the amusement of the crowd. The notebook was among them and whoever bought it considered it sufficiently important for preservation. The various owners since then are unknown but it came up for sale at Sotheby's, the fine art auctioneers, at their salerooms in London in July 2002 when it fetched £14,340, a sum that would ironically have settled all of the unfortunate Dr Dodd's financial problems had it been realised in his day. As it is, the unfortunate Dr Dodd is now largely forgotten in Bourne although the dedicated service given to the parish by his father, the Rev William Dodd, as Vicar of Bourne from 1727 until 1756, is remembered by a ledger or memorial stone which can be found in the floor at the west end of the Abbey Church recording his life and death and that of his wife, Elizabeth. |