|

THERE HAS BEEN a police presence in Bourne for 150 years and law and order has been maintained throughout that period except for one instance in the early years of the last century when for a brief time, uniformed officers lost their authority during one of the biggest cases of civil disturbance in our history.

The Second Boer War that had started in South Africa in 1899 aroused deep feelings of patriotism in English hearts but a jingoistic fervour was also whipped up by the popular press and soon spread throughout the country. The conflict had began with a string of British defeats that have become bywords in our history, Mafeking and Ladysmith among them, but finally ended on 31st May 1902 after two years and seven months when the Boer leaders signed the terms of surrender although the announcement did not become public in London until the next day which was a Sunday.

The news reached Bourne soon after midday on Monday 2nd June and there were immediate demonstrations around the town and although the police were patrolling the streets, there were no infringements of the law that called for their intervention. But by evening, after the public houses had opened, the atmosphere changed and from 9 pm, the police were involved in a running battle with revellers, many of them who had been drinking heavily.

Bonfires were lit in the Market Place and South Street and blazing tar barrels rolled down the road. The police made repeated attempts to break up the disturbances but were met with such cries as: "Bring out another, boys! Get another ready, boys!" and instead of dispersing, the crowd started more fires, sometimes using fireworks such as squibs and crackers, and at one point, planks and piles of faggots stolen from the yard of the Red Lion public house were brought out to keep them burning.

The Bourne police chief, Superintendent Herbert Bailey, joined his men on the streets in an attempt to halt the demonstration and tried to prevent a lighted barrel being rolled down South Street. "I managed to stop it before it got to the Red Lion”, he said afterwards, “but stones were thrown at the police. The streets were packed and the crowd was a very disorderly one." There were also disturbances in West Street after a lighted tar barrel was rolled out of the yard adjoining Cliffe's furniture shop. The police moved in to stop it with some constables striking out right and left with their truncheons but this incensed the crowd who attacked them and many angry and violent scuffles ensued.

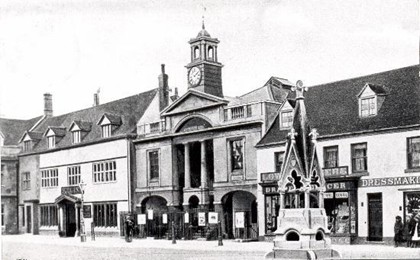

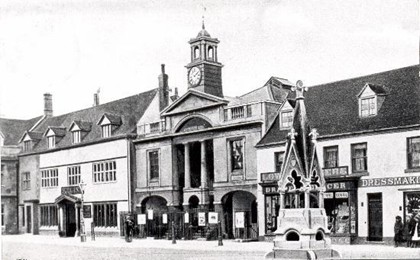

The police strength in Bourne at that time was one superintendent, one inspector, two sergeants and 15 constables, all based at the station which was then situated in North Street, but these proved to be insufficient to deal with the growing turmoil and so Bailey called in reinforcements from surrounding villages including Morton, Bourne Fen and Little Bytham, and order was eventually restored in the early hours of Tuesday morning. A total of 29 people had been arrested and the following week, on Tuesday 10th June, all appeared before a special sitting of the magistrates at the Town Hall.

There was great excitement in the town as the word went round and half an hour before the court was due to start at 11 am, large crowds had assembled in the Market Place in an animated mood and when the defendants arrived, there was a rush for the available spaces in the public gallery amid cheers for the defendants and jeers for the police.

The first 22 accused were charged with starting a fire and the other seven on a variety of offences involving assaulting and obstructing the police, throwing missiles, including fireworks, assaulting the police and resisting arrest. A total of 30 summonses had been taken out against the defendants who all pleaded not guilty and the bench agreed to hear the cases as one, a wise decision because by this time the magistrates were well aware of the mood in the town and that rioting could break out again at the slightest provocation.

They were defended by a local solicitor, Alexander Farr, who tried to discredit the actions of the police in bringing the charges against the few when the majority were equally culpable. He told the bench: “I really would have thought that under the exceptional patriotic circumstances it would have been much better if the authorities had used a little more discretion and pandered to the crowd who were not out for any unlawful cause but merely for a spree in common with the rest of the country. The whole crowd were all out to see the fire although the defendants have been singled out as scapegoats. There are others inside and outside this court house who were as guilty as the defendants."

After a day long hearing, the magistrates decided to take a lenient view but the chairman, Colonel Albert De Burton, told the defendants: “It must be thoroughly understood that a day of rejoicing must not be a day of lawlessness. The news of the peace declaration was a great occasion but there is no reason why a large part of the population should be forced to lock themselves in their houses. Nor could it be much enjoyment to the police to be knocked about. It must be perfectly understood that on the next occasion, such as the Coronation, the town must not be turned upside down."

All of the cases were dismissed except for three defendants accused of incidents against the police who were bound over to keep the peace for three months in the sum of £5. The decision brought an outburst of applause in the courthouse and cheering among the crowd that had gathered outside and the town band was quickly turned out to parade the accused men in triumph through the streets. But many waited outside the Town Hall for the departure of Superintendent Bailey who was given a hostile reception when he left and the protestors followed him to the police station hooting and jeering all the way. There was an air of jubilation in the town and the parades continued up and down the street until past ten o’clock when everyone dispersed quietly and went home. |